Zadie Smith’s NW

Maxine Swann

Two riveting scenes frame Zadie Smith’s exciting and unsettling new novel NW, recently shortlisted for the Orange Prize for Fiction. In the first, Leah, a thirty-five-year-old Londoner of Irish descent, opens her door to a desperate woman—tiny, grubby, shaking. There’s something familiar about the woman’s face, but Leah’s not sure why. Is it just one of those street faces you recognize? The woman, Shar, tells Leah that her mother is in the hospital. She needs money to take a cab there. She’s been asking up and down the street and no one has helped her. Leah, a charity worker by profession, rises to the occasion, trying to determine what hospital it is, calling a cab, making tea despite the summer heat. Shar’s the one who realizes it: they went to the same high school. As they muddle around a bit in the past, Leah sees that there’s something wrong with Shar’s face; Shar reveals that an abusive husband “broke” it. Leah finds herself telling Shar that she’s pregnant. She’s just discovered it this morning, Shar’s the first person she’s told. Shar, who has a drug problem and will end up taking Leah’s money and running, “grins satanically. Around each tooth the gum is black. She walks back to Leah and presses her hands flat against Leah’s stomach,” determining that it’s a girl and “the kind who runs away.” “Her face glazed over once more with boredom… All things are equal. Leah or tea or rape or bedroom or heart attack or school or who had a baby.”

In the penultimate scene of the book, Leah’s best friend from childhood, the smart, ambitious, focused Natalie, second-generation immigrant of Caribbean parentage, who has always done everything right and is now a barrister married to a banker with whom she has two children, walks out of the family house in her slippers and a ratty T-shirt after her husband finds a series of compromising emails on her computer, and keeps walking as darkness falls, encountering on her way a former classmate, Nathan, now a doped-up pimp, with whom she shares the rest of the night, getting higher than she’s ever gotten in her life, talking, but above all walking and walking: “Walking was what she did now, walking was what she was.”

It’s not surprising that NW has made some reviewers nervous. There is something intrepid about the territory Smith is treading into here, as if she, too, like Natalie, is taking this walk, leaving a brilliant, comfortable past behind in search of something else.

The setting is Willesden, a neighborhood in northwestern London (thus the “NW”), and, in the same way that Smith gets closer to her characters here than she has in any other book, waiting and listening and standing by as they come to life, she bestows patient attention on the city, approaching it from multiple angles, using varying narrative strategies—interior monologue, prose poetry, directions from destinations A to B that appear to have been downloaded from the internet, the sudden eruption of disembodied voices—to get its pulse on the page. As this portrait of the city emerges, the boundaries between the people who live in houses, have stable jobs and relationships and those who live on the streets, drug addicts, pimps, whores, are revealed to be much more permeable than we might have thought. And not only that, but the world of the dispossessed exerts its pull.

At the end of Jane Bowles’ Two Serious Ladies, one of the female protagonists says to the other: “I have gone to pieces, which is a thing I’ve wanted to do for years.” Leah, who has had female loves in the past, finds herself haunted by the woman who came to her door. She runs into her on the street, on a hilltop. When she goes to pick up photographs taken at a party with a disposable camera, she’s handed the wrong envelope and they’re of Shar. Like the good charity worker she is, she takes rehab literature by Shar’s house, pushing it through the mail slot, a moment which returns to her in a fantasy later as she sits out in her yard: “and so the door opening at the moment that she stands there, her hand full of leaflets, and Shar saying: put those down, take my hand. Shall we run? Are you ready? Leave all this! Let’s be outlaws! Sleeping in hedgerows. Following the railway line till it reaches the sea. Waking up with that long black hair in her eyes, in her mouth.” Leah’s secret desire for Shar is also a desire for another kind of existence, one more like Shar’s, that—far from her everyday life “with its admin and rent and husband and work”—implies abandon. But it’s fitting that Leah, whom time seems to pool around rather than propel in a straight line forwards, isn’t the one who takes to the streets. It is Natalie, mistress of masks (“Daughter drag. Sister drag. Mother drag. Wife drag. Court drag. Rich drag. Poor drag. British drag. Jamaican drag.”) who finally runs away.

Meanwhile, what are the men doing? Nathan Bogle lives on the street. Natalie’s husband, Frank, born of a chance meeting in a park between a Trinidad train guard and a stylish Milanese woman, is a banker, and Leah’s husband, Michel, is a hairdresser of West African extraction who does some private investing on the side. A third part of the book is devoted solely to Felix, former denizen of the same housing project Leah and Natalie grew up in, a drug dealer and user, who is now moving in the opposite direction, coming clean. We follow him through his day, to buy an antique car, visit his father, Lloyd, a quintessential 70s dude whose girlfriend has just jumped ship, stop in on an old lover, Annie, an aristocratic addict in her forties and, finally, after a passing, tense encounter on a bus when he urges a guy to reposition his feet to make room for a pregnant woman to sit down, we witness him get mugged and killed by that disgruntled passenger and his friend. Felix is touching, especially in the scene with his charming, impossible father, but he’s still held at arm’s length or at least at a distance that allows us to observe him comfortably in the way that most, if not all, of the characters in Smith’s previous novels have been observable. They’re interesting, entertaining, but we don’t feel implicated, close to the bone, the way we do with the female characters here.

We’re more comfortable with our men on the streets than our women. Nathan and Felix don’t disturb us the way Shar does. And we’re certainly more comfortable with our men engaging in online sex hook-ups. This is what precipitates Natalie’s fall, her husband’s discovery of the private email account that she uses to arrange threesomes with people of varying genders looking for a black woman between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five. And Smith does falter here. These encounters lack the realism, which includes the playful interest and humor, that Smith as such a vivid realist might have lent them.

Realist and master scene-maker. The scene where Leah and Michel go over to Natalie and Frank’s for dinner is delightful in its richness, the awkwardness of this encounter between friends from childhood who have not only taken different paths in life but also have partners from vastly different worlds in tow. There is the struggle to find a common language, the embarrassment of the clash of classes. Smith captures the complexity of all the different currents, her attention is everywhere. And using other tools, Smith delivers a study of a marriage in under two pages—Leah’s thoughts that are mainly sensory impressions and take the form on the page of an apple tree as she sits with her husband out in their shared London yard accompanied by Michel’s monologue: “We’re all just trying to take that next, that next, next, step. Climbing that ladder. Brent Housing Partnership. I don’t want to have this written on the front of a place where I am living. I walk past it. I feel like oof – it’s humiliating to me…This grass it’s not my grass! This tree is not my tree! We scattered your father around this tree we don’t own even. Poor Mr. Hanwell. It breaks my heart. This was your father! This is why I’m on the laptop every night.”

In other ways, though, the book resists delivering classic novelistic satisfactions. Leah’s character doesn’t evolve as expected, or even really at all. In the final scene, when Natalie could finally come through for her friend, a change seeming all the more likely given the limit experience she herself has just been through, she doesn’t: “If candor were a thing in the world that a person could hold and retain, if it were an object, maybe Natalie Blake would have seen that the perfect gift at this moment was an honest account of her own difficulties and ambivalences, clearly stated, without disguise, embellishment or prettification. But Natalie Blake’s instinct for self-defense, for self-preservation, was simply too strong.” As usual, she plays it safe.

But Smith doesn’t. It would be interesting to see how the spirited exuberance that buoyed up Smith’s earlier novels, sometimes to the point of light-headedness, but is missing here, would play out at these newfound depths. But that would also make for a very different book. In a discussion of the TV series Girls, Emily Nussbaum evokes “the dictate that women, both fictional and real, not make anyone uncomfortable.” What is so threatening about a woman falling apart? First of all, a woman on the street is much more vulnerable to physical harm than her male counterpart. But, above all, the question that comes to our minds when we see a woman who has abandoned herself is: where are the children? In other words, who is taking care of them?

Besides Shar, who claims to have three children we never see, two other figures in the book operate as specters of self-abandonment: Annie, the posh junkie who jokes about her childlessness, and Felix’s mother, who has deserted her children, showing up occasionally to steal from them. Our central characters, Natalie and Leah, are also ambivalent about motherhood. “Natalie Blake and Leah Hanwell were of the belief that people were willing them to reproduce. Relatives, strangers on the street, people on television…” Leah, it turns out, really doesn’t want children but, while Annie can say that, she can’t. Instead, while going through the motions of trying to get pregnant, she has an abortion on the sly without telling her husband. The ultimate deceit, not only towards her husband but towards society. Smith here is walking right into the heart of our nightmare.

“But I have my happiness, which I guard like a wolf,” Bowles’ character continues. By this point, both Bowles’ characters, upper class women stifled by their milieu, have descended into debauchery. No longer keeping up appearances, they have dropped off the grid. But Leah and Natalie are of a different ilk. They want “both this life and another.” Their desires contradict. Though we all may know women in the world who struggle with the same conflicts and concerns they do, their type rarely makes it to the page. The really unsettling part is that Leah and Natalie are “normal” women with good jobs and husbands who love them and treat them well, women we can identify with and with whom we are identifying until, oops, they start expressing or enacting desires that unnerve us, all the more so when these desires strike a chord.

* *

Image: Marisela LaGrave

[ + bar ]

Yolanda Castaño

translated by Carys Evans-Corrales

“What’s wrong here is that we don’t know how to sell ourselves,” your fellow tenants would always complain. But when that guy who really had a... Read More »

John Pluecker

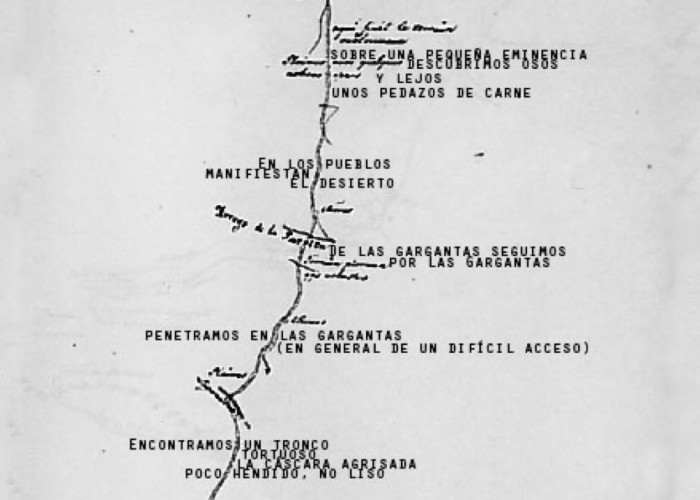

THE HUNT

A SERENE NIGHT / AT FIVE / SERENE SKY / AT SIX / OR AT 3 // JUST THE LIGHT / THE HOUR RISES THE SUN // SILENCE... Read More »

Paula Bohince

IRISES AND GRASSHOPPER

Client in a house of courtesans, tableau of masculine and feminine. The irises lie back, languorous, dark pink at the centers and lighter at limbs. The grasshopper, in his armor, grips... Read More »

Yolanda Castaño

“Aquí o que nos falla é que non nos sabemos vender”, queixábase seguido o teu patio de veciños; pero cando chegou para o quinto dereita aquel tipo que si o sabía... Read More »

sending...

sending...