On Repetition: Nietzsche, Art Basel, and the Venice Biennale

Mariano López Seoane

translated by Pola Oloixarac

In fairy tales, curiosity, one of the forces that sets the story in motion, is always punished. This ancestral warning has stopped few, even though punishment has rained down upon us from Eve’s appetite for apples to the present day. It was the desire to see things up close, to be where the action was, that drove me to visit the Venice Biennale and Art Basel in the space of two weeks. The punishment was not long in coming. Like a hero in disgrace, I was condemned to repetition: in both places, the same artists, the same names, the same questions and, what’s worse, the same experience.

There’s little to say, in critical terms, about Art Basel. It’s a fair: it aims to sell works and make names circulate, ignite careers, turn artists into stars. And that is exactly what it does. All critical cannons are aimed at the Biennale, which presents itself as an intellectual, or at least a reflective, exercise. The fact that it’s hard to establish a clear distinction between the two events speaks of the direction the Biennale has taken, but also about major changes in the art world and the culture industry behind this change. What follows is an attempt at capturing these transformations.

Repetition Hell opened up under my feet at Basel. I arrived in the Swiss city a little tired after an exhaustive inspection of the Biennale and its excretions. I didn’t know much about the fair (beyond its reputation for being the biggest art fair in the world) or about the city (I only knew of its Roman past, and its place in the tortured biography of Nietzsche). It’s possible that the insistent buzz of his name conditioned, or telepathically imposed, a receptivity to what returns.

Nietzsche taught at the University of Basel from 1869 to 1879, in what would be his only formal tie to a teaching institution. At the time, he was a young promise in the field of classical philology. Health problems, and his growing weariness of academic conventions and repetitions took him to quit. He left Basel to become an independent, traveling author. Only then could he focus on composing his greatest works, The Gay Science among them, where, in section 341, he presents for the first time the eternal return as the ultimate test. Let me explain: Beyond cosmological pretentions, the figure of the eternal return can be understood as proof that we’ve reached what the philosopher understands as the height of human greatness: amor fati, the love of destiny. If, when faced with the prospect of having to repeat our lives for all eternity just as we have lived them, we are inclined to accept, then, says Nietzsche, we are demonstrating the highest affirmation of life, the greatest love for life’s twists and turns. This would be a transcendental, positive repetition crucial to the affirmation of life, and quite different from the mind-numbing repetition of routines, academic work and, we could add, of the market.

The first effect of my double voyage was an objective déjà vu: the artists highlighted in the Biennale reappear in the more openly commercial displays of Basel. What’s more: some of the works that could be acquired at the fair seemed to complete what the Biennale didn’t propose as a series, but the fair revealed as such.

Berlinde De Bruyckere shines in the Belgian pavilion of the Biennale with her monumental zombie tree trunk, but lays down just two little sticks (a -dead?- deer on a table, and a small trunk) at two of the Fair’s central stands. In the section of the Biennale curated by Cindy Sherman, Paul McCarthy exhibits a doll that seems like something straight out of Sesame Street; conveniently, in Hauser and Wirth, he presents a Snow White made of black silicone belonging to a series he did a couple years ago at the Armory Show. George Condo, who shot into the pop firmament after the cover he designed for rapper Kanye West, also makes a double showing (multiple, in fact, since his work appears in several galleries). Alfredo Jaar presents an interpretation of the Apocalypse tailor-made for Venice, and an excessive intervention in the Unlimited section at Basel. Jeremy Denner shoots us a dose of English Magic in his curatorship for the British pavilion, and reappears with a simple print (“Bless this Acid House,” 10 editions, sold out) at the stand of Parisian gallery Art Concept in Basel. The omnipresent Ai Wei Wei, as vast as the Chinese Empire, proliferates at the origin (in Venice, in at least three different places and circumstances) and returns at the fair. Llyn Foulkes’ deforming portraits can be seen at Punta della Dogana and the halls of the fair. Thomas Schütte’s neogothic sculptures reappear everywhere. Rikrit Tiravanija is also present in the two cities of global art. The examples could multiply (eternally?), forming what Graciela Speranza has called the “globalized checklist” that defines contemporary art today.

The question is whether the art at the Biennale and Basel can pass the test of eternal return, or whether we are standing before a repetition of another kind, the banal repetition that haunted Nietzsche in his days as a professor. In any case, and as Nietzsche would have wanted, the Eternal Return Test can serve as a measuring stick to distinguish artworks that break through the desert of ennui created by the rest, artworks that turn their gaze on us, capturing the light and shadows of the present, open to today, to the future, and to the archaic, from those frozen in the category of symptoms. In either case, faced with these two types of repetitions, criticism has something to say.

Let’s start by affirming life: let’s fix our eyes on the artworks we could revisit over and over again, for all eternity. They are few, they can be counted on two hands. Five come to mind at the moment: the aforementioned Berlinde De Bruyckere at the Belgian pavilion; the SS Hangover ship by the Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, on the shores of the Encyclopedic Palace; Mathias Poledna’s video at the Austrian pavilion; the barely perceptible performance by Tino Sehgal at the entrance to the Giardini; the mock-encyclopedia by the Swiss artists Fischli and Weiss.

I think these artworks stand out from the rest of the exhausting itinerary because they cultivate languages that set them apart from the manic pulse of the Biennale, because they make us question the grammar of the spectacle, because they highlight an emerging dissent, and offer a warped image of the circuits themselves, fostering a critical distance not always present at these events.

Their significance comes through most clearly against the backdrop of the conditions of reception of the works at the Biennale and Art Basel. The overwhelming quantity of artworks; the mingling of techniques, languages, traditions, horizons; the fact that, even at the Everest of spatial design, we are visitors to a mind-numbing heap of artworks, names and cultures. Everything conspires to make these itineraries a confusing experience in which one learns as much as one forgets, in which one’s senses and understanding are stupefied like those of an inhabitant of a megalopolis. Where one experiments not the artworks, but rather the internal logic of the itinerary: its speed, rhythm, and lack of relief. All in all, the experience is closer to that of visiting an amusement park than an exhibition at a gallery or a museum. This manic pulse is the first thing reverted by the aforementioned artworks. Let’s see how.

Right after the impressive architecture of the Arsenale, Ragnar Kjartansson’s “S.S. Hangover” surprises the fatigued visitor. After hours of walking and seeing without looking (a sort of immunological response to the confusion), his legs, head and eyes are sore. After the main event and a series of national pavilions, the view opens onto the water (the channeled sea), a surface that invites you to sit down and relax. That’s where the Icelandic artist placed his ship, a fishing boat redesigned with Greek, Icelandic and Venetian patterns. Like the visitors to the Biennale, the ship repeats a mechanical itinerary. But it does so at a pace impossible to sustain in the frenzied succession of halls and pavilions and the reflux of visitors: crewed by a sextet playing a piece for wind instruments specially composed by Kjartan Sveinsson, this “kinetic sculpture” maintains a slow pace—more like drift than travel. Indeed, the ship goes nowhere: it travels from one point to another along the wharf, in the shape of a U. A controlled, limited drift that invites the viewers to question the sense of their walks and provides them with a much-needed moment of relaxation. The grateful visitors gather in the grass by the dozen; the proof of the restorative, healing effect of Kjartansson’s work is found in the amount of time they spend there, given to contemplation, a practice seemingly banished from the rest of the Biennale.

It is quite possible that, seeing this artwork, the viewer resumes a capacity for action that the cruising speed of the official itinerary forbids, or at least debilitates.

The remaining pieces provide a similar repose, allowing the visitors to engage their interpretive apparati. The installation prepared by Berlinde De Bruyckere for the Belgian pavilion opens up like the gullet of a mythological animal. The almost blinding luminosity of the Venetian spring and the Biennale rooms finds a fierce counterpoint: the pavilion is almost completely dark. The only illumination comes from a filthy skylight, where opacity claims the advantage over transparency. The viewer’s advance necessarily comes to a halt.

Our eyes need a few minutes to adapt to this new environment; when they do, we can only move in cautious, small steps. At the center of the room, where the darkness is less dense, stands what the artist, in collaboration with JM Coetzee, has called Kreupelhout: the trunk of a zombie tree, scarcely alive, barely strong enough to search for light. It’s a sculpture that brings the dark forces of nature, the haunting whispers of the woods, into the shrine to encyclopedic vanity. Kreupelhout seems to speak both of a past that we willfully block from our sight, and of a future of ecological disaster and genetic mutation. Standing before it, the viewer’s response can only be emotional: alone, surrounded by shadows and icy currents of air, the viewer beholds the agony of a semi-living being, half human work, half error of nature. He is caught—perplexed, speechless—between the desire to flee and the will to help.

It’s no accident that De Bruyckere’s project involved the collaboration, in the form of curatorship, of a writer. The process of creating the installation, documented in the catalog of the pavilion, entailed a back and forth over emails between the artist and the writer, in which suggestions, corrections, and encouraging words were exchanged: all this was set into motion by a short story Coetzee sent De Bruyckere at the end of 2012. Here, this sporadic contact and elective affinities conspire in the creation of a monstrous work that distances itself from the “professional” supervision and bookkeeping of aseptic curators, always looking to make a splash.

The monumental, unfinished piece by the Swiss artists Fischli & Weiss also brings us to a halt, for other reasons. Their famous “Plötzlich, ein Übersicht” hides in a central room within the Giardini, only accessible via a narrow stairs. Two guards stand at the entrance, forcing the visitor to line up to see the work. The wait provides an initial deceleration. The work, a vast 3D encyclopedia of small figures made in clay, demands a detailed, slow motion examination.

The viewer’s gaze is necessarily tender: the Lilliputian size of characters and scenes lends itself to a respectful, almost intimate close up, yet the succession of scenes ends up raising a series of questions, inspiring reflection. The artists gathered together their personal obsessions, building an encyclopedic work-in-progress that calls into question the all-encompassing pretensions of the Encyclopedic Palace and mocks the enlightened ambitions that serve as the premise of that endeavor, and others. Nevertheless, what they offer is a labor of love: love for tradition (by reconstructing a humanist canon we could call romantic, ranging from the figures of Goethe, to Frankenstein’s monster, to Freud); love for certain moments of the culture industry (TV characters, the Rolling Stones); love for thought and philosophy (many of the little sculptures represent concepts like Theory & Praxis).

The two remaining artworks are unique in that they transcend the hell of repetition by making use of repetition. The animation presented by Mathias Poledna in the Austrian pavilion invites contemplation on loop. It’s a short film produced using the animation techniques of 1930s Hollywood. A character that could be a dog or a rabbit takes a stroll while singing a song. Other animals join in and sing along; even flowers wake up to say hello. Walter Benjamin has analyzed the utopian potential of prosopopoeia in Mickey Mouse. The impact of the video, in this context, is more modest, though: a new pause in the darkness, a moment of rest in which we are all eyes and ears. Peaceful, comfortable, we surrender ourselves to the mimesis of one of the first forms of cultural industry as though it were a soothing balm. The video is short. We can watch it over and over again. Get in the loop. And take advantage of this state of mind to think about the conditions under which it was made, about what sets it apart from an old Hollywood film (where does art begin and end?), about a natural landscape that is not seen as a friendly wonderland anymore. About the pleasure of senses as a horizon in and of itself, one that is typically dimmed, or banished entirely, by art seen at Biennales. The artwork is simple, candid, yet it opens up a space for questions that other monuments to sophistication don’t manage to pose.

The specter of the loop is also present in the winning performance by Tino Sehgal. Almost imperceptible, it takes place in one of the central halls of the Giardini; in a way, it disturbs the contemplation of the artworks hanging on the walls. Upon entering the hall, the visitor hears a swarm of sounds, from howls to drumming. Immediately, the viewer discovers that the sounds are made by people, by then revealed as performers, kept at bay in a corner of the room, who use their mouths as versatile instruments, improvising an unstable choreography that consists of just a few steps. This choreography and cacophony goes on as long as the Biennale is open. The continuum is repeated—if we can speak here of repetition—day by day, from the first to the last day. Rather than repetition, Sehgal in fact proposes a reflection on its impossibility. Every day, the performers are the same; what changes are the combinations—directed by Sehgal—that make up the groupings, and the sounds and movements they improvise.

Paraphrasing Hegel, Borges once wrote that music was the most perfect form of time. This intervention adds the human body to the phrase: music and dance, syncopated and erratic, yet contained in space, are offered as the most perfect forms of time for the Biennale visitor. Indeed, without even knowing what’s been seen (there are no signs indicating this is an artwork, or declaring authorship of any kind), the viewer stops at the threshold, or uncomfortably at the center, observing a narrative develop with no recognizable structure, seeming to caress entropic drift. What’s destroyed, once more, is the firm step of the visitor that seeks to remain a pure observer. An unsettling contemplation is imposed upon us that makes us question again the limits of art (or our notions of art) and the pace that marks the consumption and absorption of an artwork.

We named five works of art. It is telling that, together, the great colossus of contemporary art (Documenta completes the Holy Trinity) produces barely a handful of memorable artworks, to be treasured and eternally repeated. There is, though, an overwhelming abundance of works informed by what we could call the “wow factor.” This factor dominates the selection concocted by the curator to build up the Biennale’s Encyclopedic Palace (which, from its title, aligns itself with a politics of exclamation). What’s interesting, or alarming, is that this selection coincides on so many levels with that of the market, as manifested in Basel. We are confronted by a repetition, in the works themselves but also, beyond them, in the contemporary experience of art. Indeed, repetition determines this experience, giving it the peculiar taste of something already known. The experience repeats like an ill-settled meal.

A sympathetic party might offer the following hypothesis: duly informed of the treasures that would be on display in the Ark of the Biennale, the world’s major galleries choose to (or have to) take advantage of the exposition, publicity and legitimization (by the sector of the market controlled by curators and critics) of their artists; as such they commission a work in a sellable format for their stand, an obvious yet nonetheless astute way to commercialize the je ne sais quoi of participation in the Biennale. It’s a perfectly rational, transparent strategy, which could be observed earlier on in Buenos Aires, more precisely at ArteBA, where the auction house Roldán offered a remnant of the monumental (and repetitive) piece that Nicola Constantino would present a few weeks later in the Argentine pavilion of the Biennale.

Meanwhile, those with a penchant for conspiracy theories—not delirious ones—might argue that there are questionable ties between the curatorial team of the Biennale and the directors of the most powerful galleries on the planet, who, from their positions of power, could have influenced the decisions of the Head Curator, the President of the Biennale, or the curators of the national pavilions. One could imagine (even discover) a murky system of returns.

Both interpretations are viable, and their exploration may bear edifying fruit. But let’s look beyond the craftiness of the gallerists and the amoral shenanigans of the great art companies and their highest functionaries, and consider the structural conditions for this trite, non-sublime, repetition that fails our Nietszchean test. Indeed: which traits of the contemporary art world would explain the family resemblance between the market’s fairs and their counterparts in the realm of ideas? A Biennale is, after all, an event for thought and intellectual dialogue, a space for exchange among artists, curators, critics, and audiences.

Isabelle Graw’s High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture (recently translated into Spanish by Cecilia Pavón and Claudio Iglesias) offers some hints in this direction. The book can be read as a symptom: her attempts at defining the two worlds (the “art market” and the “knowledge market”) fail consistently throughout the book, almost like negative proof of her hypothesis. Graw alternates between insisting on the separation of what she defines as two independent worlds, and recognizing that the categories she’s using no longer serve. In a wonderful paradox, the failure of her argument brings forth the phenomenon in bold letters. Graw adopts the master narrative of many historians, brandishing post-Fordism to explain the subordination of art to celebrity culture and the growing role of the market as arbiter of art, assigning value in every sense of the word. What is brought to light is the loss of autonomy of the “knowledge market” in the face of the growing hegemony of the market as such: the fact that an artwork has a commercial value is enough to secure its value in the art world. Undoubtedly, this plays a key role in the bad repetition we’ve been talking about: artworks consecrated by the market, in Basel and at other fairs, gain visibility and become part of the cartography of contemporary art as mapped by the Biennales.

But other elements should be taken into account when thinking about this repetition, in order to paint a broader picture of the collapsing boundary between two art markets.

Beyond the celebrity status gained by many artists (such as Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Georg Condo, and Tracey Emin, among others), events associated with the contemporary art circuit have become part of the world of show business. Biennales and global art fairs are forced to fit on an international calendar that includes not only Cannes, various fashion weeks, and global parties, but also soccer’s World Cup and the Olympic games. Thus, the events of a supposedly autonomous world (art) have become part of the dynamic geography of the global spectacle, absorbing some of the key features of mass spectacle as defined by Walter Benjamin, and losing, along the way, much of what made it unique. And so the experience of visiting a Biennale feels more like visiting a mall or an amusement park than like visiting a small show in a museum or an artist’s atelier.

The key to all this can be found in the mass character of these events, as though the spectacle was the only language Modernity (and its many post- avatars) had learned for dealing with the gathered masses.

Walter Benjamin saw a political potential in these developments. The diffuse or distracted reception always allowed by architecture became, in the age of technical reproduction, a model for art emancipated from the aura, able to be politically repurposed. The motto in this famous essay was: politicize art as an antidote against the growing aestheticization of politics promoted by fascism.

Let us simply say that 20th century history documents the life of both options—that one is not enough to counteract the spread of the other. The political and the social’s growing engagement of the logic of show business is, in fact, not the exclusive patrimony of fascism, but rather a current reality, the byproduct of the industrialization of culture, what Adorno and Horkheimer would later deem “monopolic capitalism.” The vignettes in Adorno and Horkheimer’s essay, like the aphorisms in Minima Moralia, can serve as a starting point for an interpretation of the show put on in Basel and Venice; a spectacle that, without question, knocks art off its high culture pedestal—but without giving us anything in return. Benjamin’s proposal of politicizing art is practically annulled by the format that regulates both spaces. Only where a different logic and pace emerge, where viewing art is something other than taking a tour with predetermined pauses, speed and wow moments, can one find a space for reflection and thought. That’s what these artworks I listed before offer us.

It should be said that they are not alone. These artworks join other efforts silently navigating the Palace rooms and the pages of the Encyclopedia, works that the pace of entertainment encourages one to overlook. Partly because it’s hard to portray them as highlights, and even more so because it’s hard to sell them. It’s precisely those works that are not repeatable, in the flat sense in which George Condo, Ai Wei Wei and Paul McCarthy can repeat themselves. And yes, I said works: many are not even works of art. There has been much talk about the Biennale’s young curator Massimo Gioni’s choice of outsider art. Alongside the big names and emerging artists, there are housewive’s drawings, dolls devotedly hand-made by amateurs, voodoo flags, offerings to religious temples, etc. Beyond these examples of an extra-artistic impulse (in itself a way to challenge the commercial drift: how does one sell a voodoo flag collection?), we have the works of artists and intellectuals dedicated to exploring an interior world.

It doesn’t really matter that this interior world is a fiction; less powerful, interesting fictions have fostered meaningful explorations. And this is precisely what the Biennale produces in this respect, in very diverse ways (more than an interior world, one might have to speak of interior galaxies). I’m thinking about Aleister Crowley’s tarot cards, the temple-like sculptures by James Lee Byars, Carl Jung’s Red Book, Roger Caillois’ esoteric collection of stones, the mystical abstractions of Hilma af Klint. There’s something in the tone these interventions impose upon the environment in which they appear, the rhythm they set for the viewer, that sets them apart from the Palace of Entertainment. These magical objects set us in a mood, they situate us, they demand our attention.

That’s what is at stake in the good repetition, as defined by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze in Difference and Repetition: “It’s about producing in the work a movement capable of stirring the spirit beyond all representation; it’s about making movement itself a work of art, without mediation: it’s about substituting mediated representations with direct signs; of inventing vibrations, rotations, turns, gravitations, dances and leaps that cut straight to the spirit.”

Had the Biennale’s curator been faithful to the pulse of these objects and artworks, he would have made a more silent, less spectacular, probably more hermetic show, one that was much more honest and disruptive for those very reasons. Concessions to the desire to leave the viewer speechless and to art consecrated by the repetition of the market make this journey an echoless experience, like a panoramic tour of counters full of commercial products. Naturally, a visit to the supermarket can be instructive, and become an aesthetic experience on its own. But a Biennale should foster the application of other skills, set up a dance floor across which our mental faculties can move freely.

This potential, this capacity to offer a profound, authentic, sublime repetition, is latent in the art world. But it remains inert, or dormant, when those spaces that could provide certain autonomy conform to the regime of the entertainment industry. The artworks I have singled out, and all the efforts to suspend the reign of the Palace of the Spectacle, encourage us to build and preserve spaces where art can present itself as a manifestation of the unrepeatable; as that which, because it is unique, we want to see repeated for all eternity.

* *

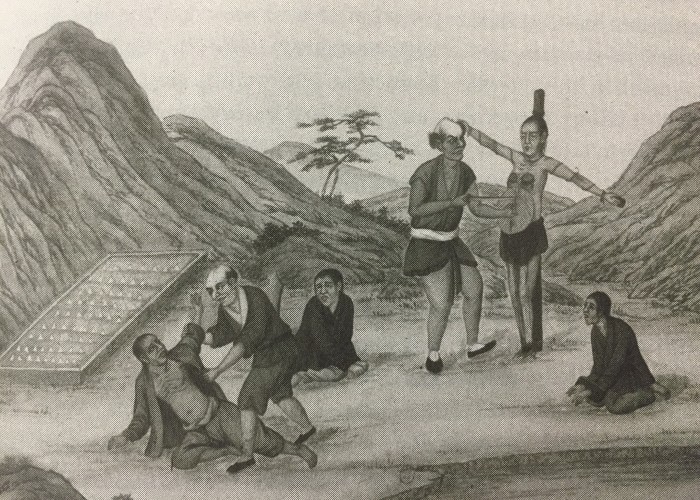

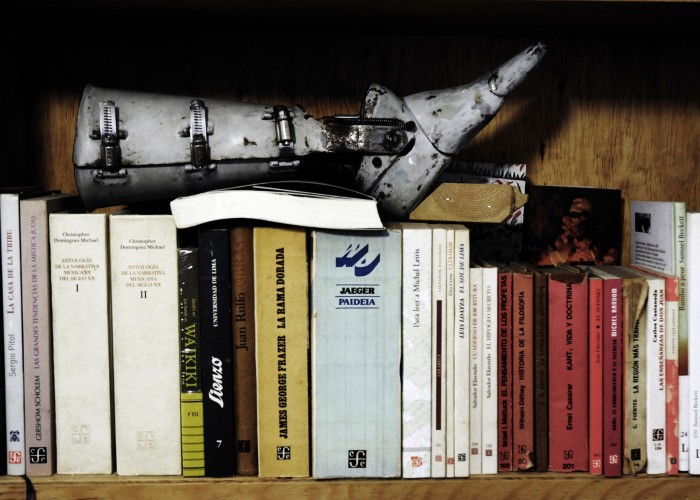

Images: Mariano López Seoane (of artworks mentioned in the text)

Counsel on the translation into English of this piece was provided by Heather Cleary

[ + bar ]

Kenneth Pobo

BERGMAN’S SUMMER WITH MONIKA

At work, she’s a game guys play between loading boxes, her home, cramped, noisy.

She and her lover sail under a high arch into an archipelago,

summer brief, a match blown out. Food gone,... Read More »

The Forgotten Sense (fragment)

Pablo Maurette translated by Andrea Rosenberg

In the winter of 1904–1905, in Beijing, a bodyguard named Fuzhuli was accused of killing his master, a Mongol prince, with... Read More »

Passagem Literária da Consolação

Julián Fuks

Chamemos de mal-estar nas livrarias. Sei que não sou o primeiro a sofrer desse infortúnio, sei que não serei a última de suas vítimas. Em algum... Read More »

Mario Bellatin: Doubles and Outtakes

Craig Epplin

Y el eco es anterior a las voces que lo producen. —Nicanor Parra

The title of Mario Bellatin’s 2008 biography of Frida Kahlo, Las... Read More »

sending...

sending...