Good Enough for Jesus

Russell Scott Valentino

“If English was good enough for Jesus,

it’s good enough for me.”

—Texas Governor “Ma” Ferguson

(apocryphal)

He doesn’t want to say the wrong thing. Who knows what might happen if he did? Everyone is so tense, so upset all the time, despite the holidays. The heat probably. Getting Praetor up so early was not a good idea. This is just the second time he has been allowed inside, even with his many years of service. It’s cooler here and not nearly so dusty, but Praetor is no happier. His migraine of course.

“What did he say?” Praetor asks, and the interpreter repeats the word “king,” though then he says “or steward” because the word the accused employed does not seem to mean “king” at all, not in the way it is usually used, though “steward” doesn’t seem quite right to him either. It could be something more like “prince” in some instances, but this is perhaps a nuance Praetor will not appreciate, so he leaves the last one out. Nuances like this, he has learned, are often unnecessary, especially when people are waiting.

“Well, which is it?” Praetor asks, and now Praetor is angry, “king or steward?”

He begins to translate Praetor’s question, partly in order to give himself time to think, but Praetor stops him. “You don’t have to have a conversation with the accused to translate what he has said for me! You talk with me, not with him. What does he say, king or steward?”

He looks at Praetor, then at the accused, then back at Praetor. Praetor clearly wants one word, not a treatise. He puzzles through the rest of what the accused has said as fast as he can, so as to make the right choice. The politics of kingship is bothersome to him and seems to be interfering somehow. Steward of another realm? King of another community? Chieftain of the dominion of the spirit? Oh, that sounds awful. But “not of this world” isn’t bad, even if the meaning is murky. He wonders about the word “polis” as a possibility for a second—the city as the world, the world as the city, the world city or cosmopolis, as in the teachings of Chrysippos, and maybe that’s what the accused means, after all, perhaps he has traveled in those parts and understands these teachings—but there isn’t time to think it all through. A king without a kingdom doesn’t seem too threatening. Perhaps Praetor will be less angry with that.

“King… I think,” he says, upon which Praetor smacks his shoulder with the wooden cane he carries everywhere, and the older man lowers his head, holding back the tears.

“So, king then,” Praetor says, smiling grimly.

The interpreter raises his head, makes eye contact with the accused but cannot read his expression.

Praetor looks at the interpreter sideways, adds, “You think.” His voice is a low hiss now, and the old man realizes he will have to say something definitive.

“King,” he says with as much certainty as he can, and glances once more at the accused, who nods almost imperceptibly and mumbles, in Aramaic, “Good. Good enough.”

“I see,” says Praetor, calling loudly for the priests.

Upon which the interpreter begins to feel hot. Not from the weather hot. It’s in his ears and neck, then his chest, stomach, and groin, a sinking wave of panicked embarrassment. His legs begin to tremble, and he nearly stumbles backward. Has he said the wrong thing? Found the wrong word? He could not imagine another in the brief span of seconds he had to work with. He did his best. He listened, tried to understand, and made his choice. Oh, if only he could explain! This word, like all words, was like the other, but it was not the other. Neither Praetor nor anyone else would see that he was not providing an equivalent; he was painting a new picture with paints whose timbres the source language might or might not have. And what if he didn’t quite understand correctly? What if there were a timbre in the source that he had never heard or seen before? Something from the accused’s childhood, or village life in a village he’d never been to, or a mumbled prefix like pseudo or demi or quasi, or a suffix swallowed altogether that made a positive into a negative or a negative into a positive? What if he had extrapolated too much based on his own paltry understanding of such things and the world? He is no expert, not in this sort of conversation, or in anything really. He knows only words. Imperfect yet precise, and so powerful. What if the words he used were harmful in some way he could not know now?

He feels another wave of heat in his ears and weakness in his legs, and he glances quickly around the room to see what is happening with all the noise in the courtyard. As his eyes, brimming with tears, pass over the accused once more, the younger man speaks again, under his breath, so that only he can hear, and the words, gentle as they are, make the old interpreter want to cry all the more.

“Don’t worry,” whispers the accused. “No one will remember your presence here anyway.”

* *

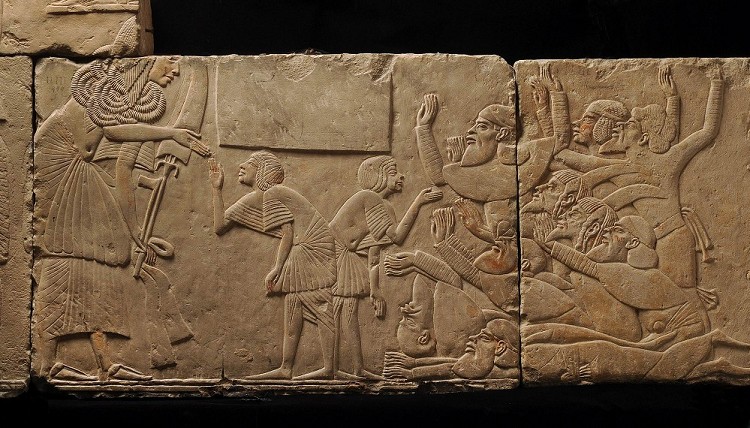

Image via the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, suggested by Ellen Elias-Bursac

[ + bar ]

La Inestable [lima]

Alicia Bisso translated by Heather Cleary

I never liked poetry. My self-imposed task of learning to read it began with a strange discovery. One afternoon, a traffic jam... Read More »

Passagem Literária da Consolação [são paulo]

Julián Fuks translated by Sarah Bruni

Call it bookstore anxiety disorder. I know I’m not the first to suffer from this affliction, and I won’t be the... Read More »

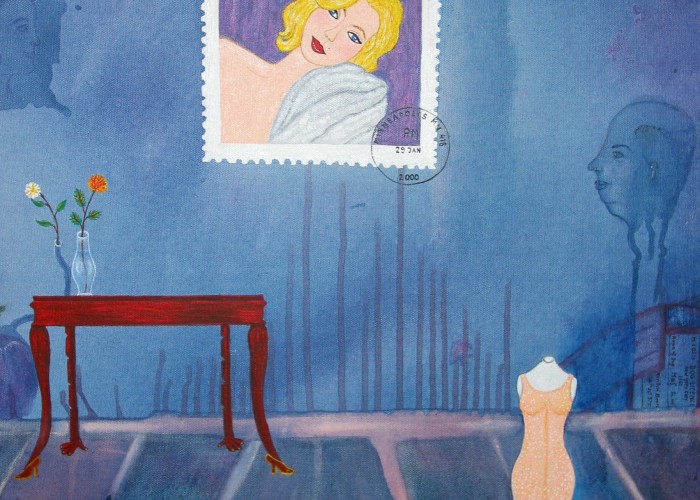

Marilyn Monroe, my mother

Neda Miranda Blažević-Kreitzman translated by Ellen Elias-Bursac

Many people wrestle with discomfort and fear when they travel by air. Dino Lučić and Veljko Linić were... Read More »

Marina Mariasch

translated by Jennifer Croft

HOW WILL TERROR TAKE ROOT IN THE FUTURE?

We jump right in, head first. The beginning is incredible. Halfway through is incredible. You quit smoking. We do the... Read More »

![La Inestable [lima]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/La-Inestable-700x500.jpg)

![Passagem Literária da Consolação [são paulo]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/fuera-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...