Instructions for Navigating in amongst The Dead, followed by a Requiem

Paola Cortés Rocca on Bruno Dubner’s Las Muertas (The Dead)

translated by Jennifer Croft

1. Images are wily: they don’t lay out facts, don’t make any cases. They’re indolent and superficial: they would have us believe that the world is what we see, and that it’s just fine as it is already. They reside as far away as possible from Comprehension, which begins where we resist appearances and first glances.

2. “When we are afraid, we shoot. But when we are nostalgic, we take pictures,” said Susan Sontag. Photographic discourse is elegiac and crepuscular: it not only cherishes the past, but also converts into past everything it touches. Salvaging it, damning it, protecting it, asphyxiating it. Photography is an overprotective mother, sweet and terrifying. A melancholy lady in eternal agony.

3. In the new regime of technology dominated by the digital, certain characteristics that may be attributed to visual and linguistic “information”—objectified in artworks, digital books, websites, even watches with no hands—are useful, too, in establishing the way in which that information circulates, the way in which subjects—producers, artists, writers, readers, consumers, etc.—make connections, amongst themselves, with others, with words, images, and the things that support them. Everything is (read: should be, aspires to be) ephemeral and disposable and, at the same time, everything is worth being recorded, catalogued, and archived; everything changes vertiginously, aspires to be updatable, to mutate into new and improved versions of itself while also remaining static enough to incorporate discrete elements that attach to and multiply the same basic platform. The approachable, the intuitive, the easy-to-use reified sarcastically the punk utopia: billed as accessible to all, it is in reality the distillation of absolute specialization, training, and research. We are more intimate than ever before—with other people, other geographies, and other histories—and yet we have never been so distant.

4. The digital is a new regime of technology (Bishop), but it could also be called a new mode of reproducibility (Benjamin) or a new redistribution of the sensible (Rancière). What is clear, however, is that analog photography, as a citizen of Modernity, also inhabits this unstable and ultra-contemporary universe. Photography is very twentieth-century, very aged. Photography is classic, modern, bold, and every so slightly passé. “Yo soy aquel que ayer nomás decía / el verso azul y la canción profana.”

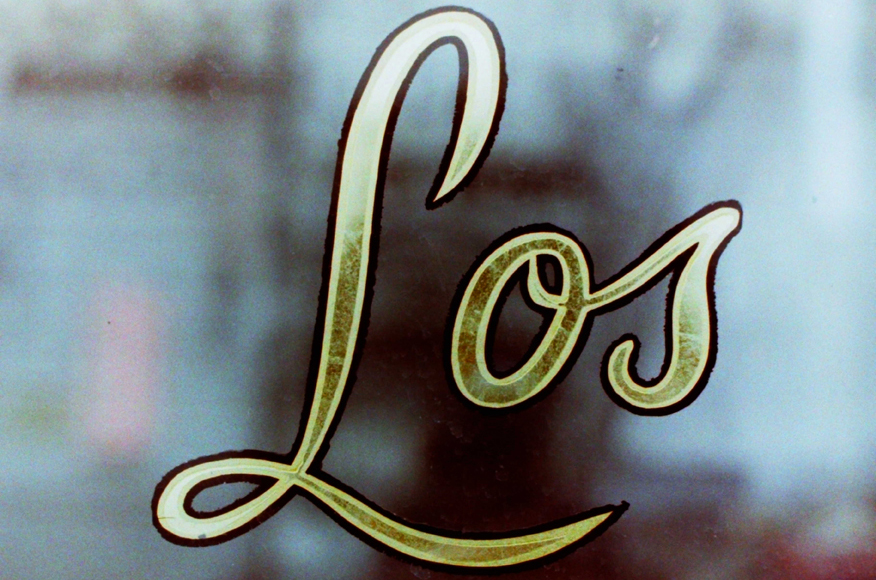

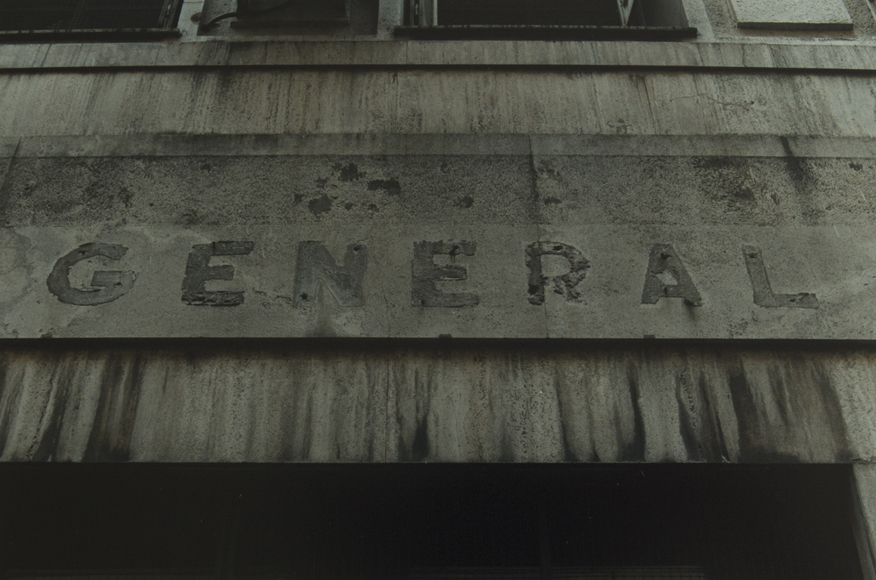

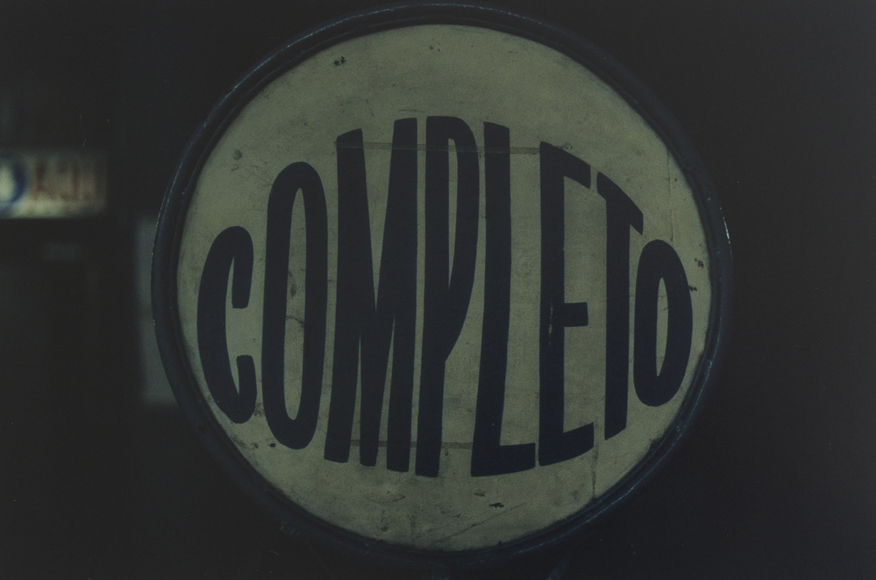

5. In his Course in General Linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure describes the sign as a psychic entity in which the signified and the signifier are unified by arbitrariness. Signage holds pre- or post-Saussurian signs. There the word is very far from being a psychic entity, be it more or less virtual. It is an object, a thing chiseled onto stone or marble, stamped across glass, resplendent, that then deteriorates and finally rots away. “Gold letters, metallic letters,” announces one sign captured here by the camera of Bruno Dubner. Furthermore, design, typography, materials are nothing if they are not opponents of the arbitrary. There is even some humor in the O of the “Lotto” that contains a lottery drum, as though the word itself were playing. Even if our vision begins to fail us, and we need to go to an optician, we can rest assured that there will be no actual reading required in the signs for them—all we have to do is recognize the typography. In signage, the word explores its analog face.

6. There are two stories present in any history of the promotional sign: the one about styles and the one about uses. The first spans the Belle Époque and Toulouse-Lautrec, Art Nouveau, Bauhaus, Russian constructivism. The second speaks to the metamorphoses of the sign from its beginnings as an instrument of advertising designed to sell things and services (drinks, plays, experiences) through its career during the World Wars as a bonds-collecting tool and an encouragement to join the armed forces. The sign is a hybrid being: it signals the meeting, in the second half of the nineteenth century, of art and market, esthetics and civil intervention. Today, when there is nothing but the blurring of boundaries between design, aesthetics, market, advertising, politics, consumption, recreation, and war, signage is a venerable old lady, an illustrious antecessor. “Hora de ocaso y de discreto beso / hora crepuscular y de retiro.”

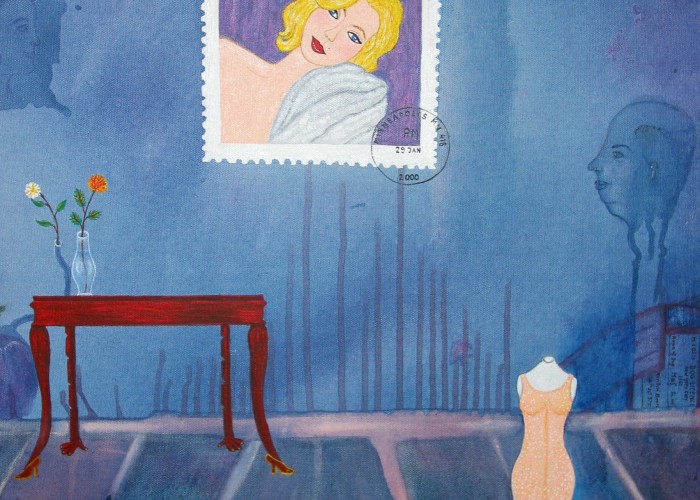

7. Asked about some of his pictures illustrating signs of Buenos Aires, photographer Bruno Dubner rejects terms like retro or vintage in characterizing his work. His thing is a liking for the old. He also maintains that his relationship with analog is not a kind of fetish (let alone gerontophilia or necrophilia). It’s part of a documentary task in which the oldness of signage is recorded by means of similar age: analog photography. He is exhibiting the results of this labor in a show entitled Las muertas (“The Dead”).

8. “This is not a pipe”: Magritte’s painting shows the ontological, aesthetic, and political distance between the object and its representation. The Dead: Dubner’s photographs head in the opposite direction. Two technologies start to look alike, making a mode of visual representation equivalent to a linguistic form, flirting with the confusion between aesthetic object and merchandise. Las muertas makes note of the scriptural character and the objectual dimension of analog photography, and at the same time, it records the visual becoming of the word in the universe of the promotional sign. “This is not a pipe.” The assertion is now obvious. What we often forget today is exactly what Dubner’s pictures point to: there can be no representation without medium, materiality, support. And that, in adding its meanings and its own history, changes everything. Who believes the word Coca-Cola, the brand, and even the beverage itself could exist in a grim Arial 12?

9. The Dead says that analog photography is traces, brand, symbols, writing. Signage is design, composition, color, highlighting, the display of meaning. The photographer documents their long-lost beauty, their glorious past, their end. He tracks them like a detective. And he finds them rusted, tattered, like the faded letters of the word “epoch” (click, a picture is taken, and it becomes forensic). This is, in fact, a funerary rite.

10. On behavior at funerals, Manuel A. Carreño writes: “Those accompanying must walk at a slow pace, and with an air of circumspection and devotion that befits both the nature of the ceremony and the situation of the mourners, for it is always a sign of good manners to show that one shares in the grief of those especially afflicted.” (Manual of Civility and Propriety Applicable to All Youth of Both Sexes, Caracas, 1853).

Requiem

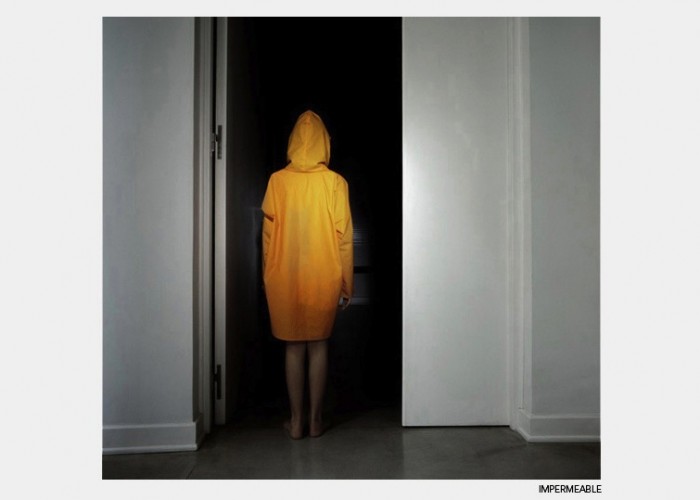

The death of god, the decline of man, the culmination of history, the end of art. These are all predictions for the future, evaluations of the present, theoretical preoccupations, urges that guide aesthetic practice, experiments, challenges, and releases. They are also melancholy celebrations, shows of fascination and of fondness. There is a vampire plot to The Dead. Not only in the hazied boundary between celebration and wake, between consecration and obsequies, but also in the moment where the death of signage is declared alongside the death of the analog image at the very same time that the former is brought back to life through the eyes of the latter. The photographer turned documentary-maker, detective, or forensic pathologist celebrates every find in games of framing, precision, and flashes of humor. Perhaps because, with its cheerful funeral and its living dead, Bruno Dubner’s work reminds us that it is just when a medium gets old that it can say anything or think everything. Thus Las muertas exhibits the paradoxical concurrence between obsolescence and utopia.

* *

Translator’s Note

The following quotes from this piece are Rubén Darío’s:

Yo soy aquel que ayer nomás decía

el verso azul y la canción profana.

I am the one who just yesterday spoke

the blue verse and the profane song

Hora de ocaso y de discreto beso

hora crepuscular y de retiro.

time of sunset and a discreet kiss;

time of twilight and seclusion

From Will Derusha and Alberto Acereda’s translation of Rubén Darío in Songs of Life and Hope / Cantos de vida y esperanza. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

* *

Images: Bruno Dubner

Las Muertas * Galería Foster Catena * Honduras 4882 * Buenos Aires * until September 2013

[ + bar ]

The Amazing Argentine [excerpt]

John Foster Fraser

Lucas Mertehikian

translated by Jennifer Croft

In 1899, Scottish writer John Foster Fraser (1868-1936) made a name for himself in Great Britain with... Read More »

Marina Mariasch

translated by Jennifer Croft

HOW WILL TERROR TAKE ROOT IN THE FUTURE?

We jump right in, head first. The beginning is incredible. Halfway through is incredible. You quit smoking. We do the... Read More »

Marilyn Monroe, moja majka

Costa Rica: The Modern as Contemporary

Ben Merriman

Costa Rica’s Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MADC) is located in a disused liquor distillery in the capital city of San José. The building still... Read More »

![The Amazing Argentine [excerpt]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/amazingargentine00frasrich_0037-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...