Omnia Caro Tenebrarum

Pola Oloixarac

translated by Maxine Swann

The living and the dead at his command,

Were coupled, face to face, and hand in hand

Virgil, The Aeneid, VIII 483-88

In rock caves like these, Cicero reports (Aristotle confirms) the obscure metaphysics of the Etruscan pirates. Their domination spanned the Tyrrhenian Sea up to the Cisalpine Gaul as far as Alalia and the Latium, before the coalition of Carthage; Herodotus mentions that “their ships brandished enormous golden spiders or gigantic octopuses.” They secured the ships to rocky formations of alum, remnants of the marine floor elevated to the surface that was man’s; then they descended with ropes into the caves turned tombs.

(These grottos have been known to attract human beings. They are not indifferent to the organic. It’s the voice of the tundra that coats beings with its excretions, without distinguishing their provenance. The cave imitates the insects that enter it on intimate expeditions, in crystal formations that parasitize.)

Under the rule of their king Mezentius, the Estruscan pirates lay down the ropes and arranged the body of the prisoner vis-à-vis the corpse of a dead man. The two were tied together in such a way that arms, legs and eyes coincided in every detail, mouths grazing; the death of the cadaver inoculated the living body through a mysterious process that fascinated the Etruscans because they saw in it the explosive transmutation of the color palette, blushes and yellows followed by black tones, the veiny network becoming visible. A green stain in the abdomen swelling up and expanding, the pacts of the hard and the soft coming undone; the black victor devouring everything.

Darkness moves quickly over the body of the living person, whom the Etruscans don’t stop feeding so as not to interfere with the sacred phases of the pictorial communion between the living and the dead. Eventually, trailblazing worms open up a pathway uniting both bodies through the abdominal zone, pregnant with diminutive beings; when the black paints both bodies, they stop bringing food.

Experimental pioneers of the vanitas, the Etruscans meditated on earthly nature through their works. In his Confessions, Saint Augustine departs from the horror that numbs the pens of his predecessors and comments philosophically that it is human nature to be tied to a body that rots. Thinkers and agents of the inexorable image-movement, the map of the Etruscans merges until it disappears into the map of Rome.

Till chok’d with stench, in loath’d embraces tied,

The ling’ring wretches pin’d away and died.

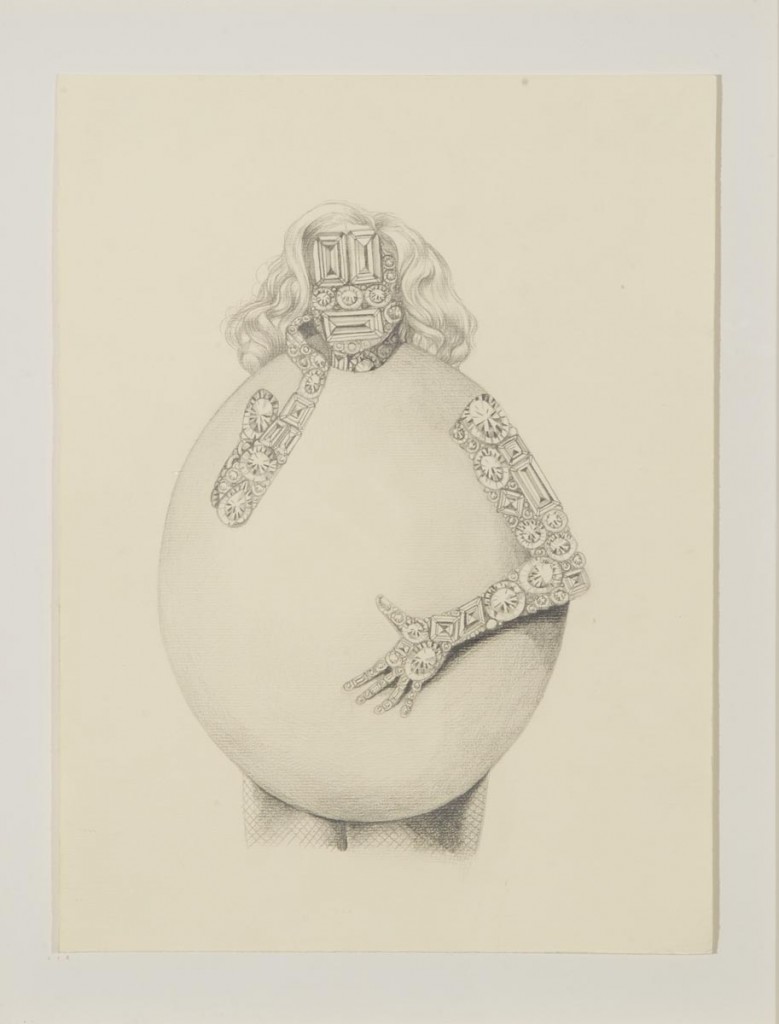

It’s probable that the moral and aesthetic suffering was truly intolerable—that the implacable metaphysics of the method killed them with horror first. The installations of Etruscan vanitas in the caves don’t eliminate this possibility: the living figure confronted with his mirror, observing close up his new face as an inhabitant of the other world. Lovers of the symmetry of gemstones (their taste for octopuses and spiders, beings whose symmetry strides two worlds, that of the radial shape of lower organisms and the bilateral towards which the human tends), the Etruscans scattered the forked monsters in the inner skin of the grotto. They created new beings with eight limbs, and populated the cave.

Virgil evokes its novelty (tormenti genus); the technique avoids the lower passions of the torturer (beatings, agitation) and introduces the innovation of death by contagion, horizontal, contiguous. The ἀγών (the human struggle, trivial) transforms itself into “agony”: the battle between two comes down to one, the condemned man devoured by the death coming from within, death that he has before him, face to face.

Stoical, the rocks of the cave observe impassibly the discolorations of the phases of the new creatures, the declensions of life radiating and decomposing. The philosophers of the Stoa, who dreamed of imitating the rock, have accepted that knowledge implied shaking off the ecstasy of ἀγών, in order to become a form of prose—the place of man in the phrase of the world. Death for death’s sake—without the mediation of an executioner.

The cave, the rope and the vigilant spectator, he who brings the nourishment.

Quid memorem infandas caedes, quid facta tyranni effera?

Di capiti ipsius generique reservent!

Mortua quin etiam iungebat corpora vivis

componens manibusque manus atque oribus ora,

tormenti genus, et sanie taboque fluentis

complexu in misero longa sic morte necabat.

Publi Vergili Maronis, Aeneidos

* *

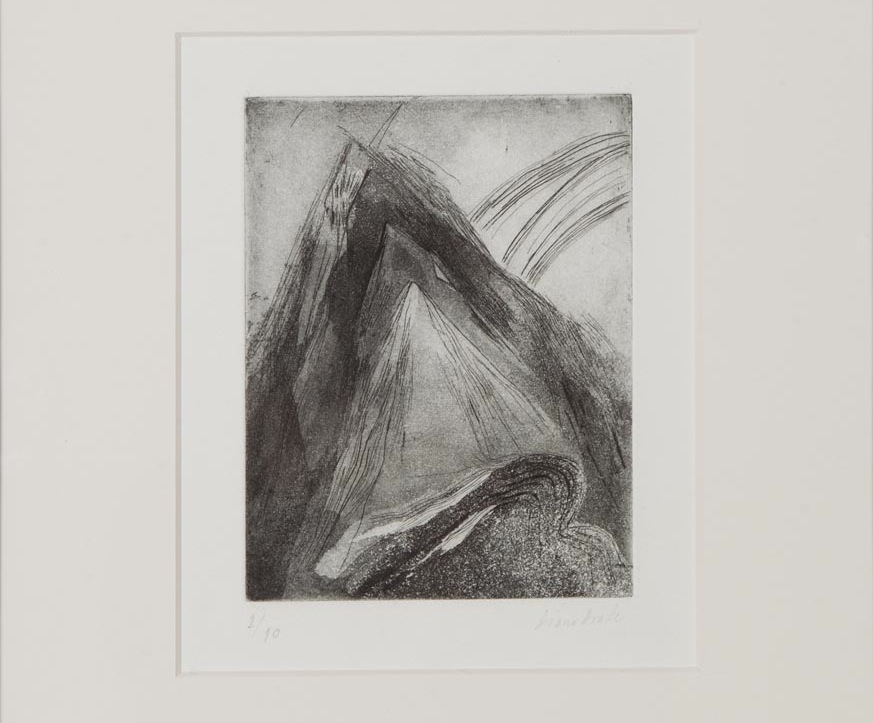

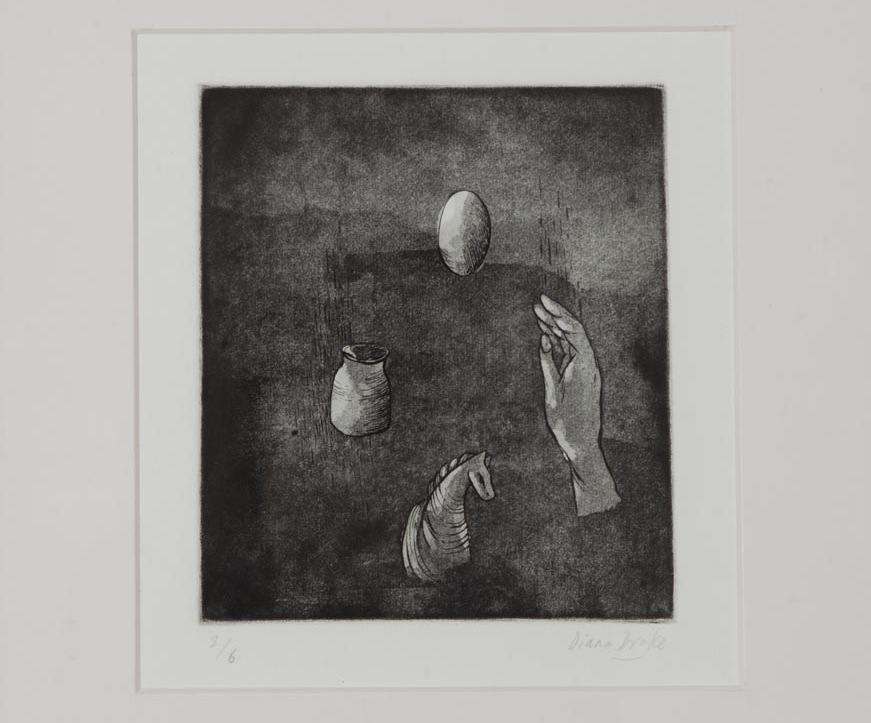

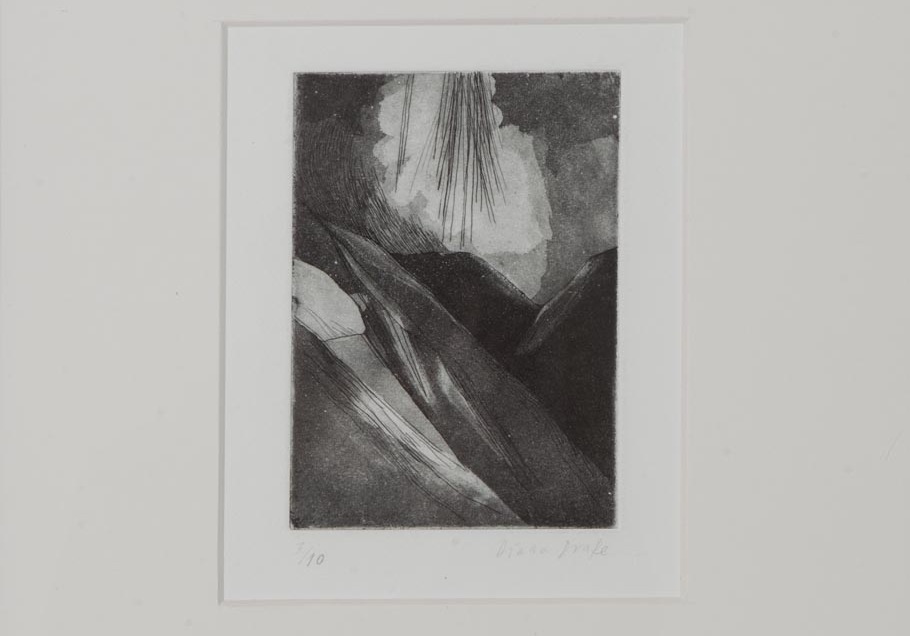

Stoa. Luciana Rondolini-Diana Drake at miau miau. Bulnes 2705, Buenos Aires. Until August 27.

Our thanks to: Esteban Bieda, Gabriel Catrén, and the artists.

* *

[ + bar ]

An American Poet’s Dream: an interview with David Shook

Interview and introduction by Pola Oloixarac translated by Heather Cleary

A young professor of literature in Los Angeles collects funding and poems online in order to make... Read More »

Lohvinaŭ [minsk]

Maryia Martysevich

The Republic of Belarus is often called “the last dictatorship of Europe,” but you’d hardly think so upon arriving in Minsk, its capital. This... Read More »

A Love Story

Bernardo Carvalho translated by Max Seawright

1.

He haggles over fish at the wharf. He’s done it since before his tenth birthday. His mother makes him. It’s no accident he... Read More »

The Reversal Spell

David Leavitt

The day that Paris was declared an Open City, I went to say goodbye to the Baron. He was one of my oldest friends.... Read More »

![Lohvinaŭ [minsk]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/bookstore_belarus-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...