The German Lesson

Eva Marer

The German teacher lived on a street of towering trees. Their weeping boughs stroked the curb, leaving sun-dappled green tunnels you could walk through. Birds flitted through the wheel-wells of cars, which seldom passed but stood parked for hours like sentries guarding their owners under house arrest. A dog barked, a child shouted; their voices—birds and children—warbled across the occasional buckshot of a car backfiring on a distant block.

Into the silence Mimi’s sobs echoed. She cried and clung to the door handle of the blue Volkswagen bus. The crown of her head was no higher than the top of the hubcap. She twisted and writhed, kicking the tire in protest. She didn’t want to go to the German lesson. She wanted to carry on and do exactly as she was doing: inertia.

“Mommy, please!” Her shrieks echoed down the street.

Behind her glasses, Mimi’s German mother Gertrud’s eyes were magnified. “I’ll buy you a hamburger,” she said, hoisting her glasses onto her nose. She attempted to peel Mimi from the door handle.

Charlotte stood idly by, invisible in her goodness.

“Don’t you want to see Daddy again?” Gertrud tried a different tack. Mimi’s special relationship with her Hungarian father, István, was well-known.

By this time, the German teacher had emerged onto the porch, her expression neutral. She never ventured beyond the porch, but waited patiently, face framed by her Dorothy Hamill bowl-cut hair. She wore slacks and a flowing batik blouse and just a touch of blush on an otherwise pale, square face.

Charlotte’s and Gertrud’s embarrassment in the presence of the German teacher was of a different order: the mother ashamed of the bawling child, the sister of the embattled mother, as she finally wrenched Mimi from the door handle, which shone like the foot of a much-stroked saint.

With a final cry, Mimi surrendered, conceding finger by finger her grip.

Mimi demanded her aloof and dignified sock-monkey doll, himself a student of German. Her free hand flew at once to her hair, which she twisted and yanked in a punishing manner. Her hair had only grown in again after the incident with the dog clippers.

Mimi allowed herself to be conveyed to the front door into the bemused and gentle embrace of the German teacher, who countered her sniffles with a complicated sentence in the dative case. Mimi could not conceive of her German teacher Helen walking on this street or, for example, going to the grocery store, but only opening the front door, releasing the smell of chipped paint and old books onto the porch to mingle there with the odor of concrete and dogwood. As soon as Mimi entered the house, she forgot her tantrum, comforted by the monkey and the rhythmic pulling of her hair.

Inside the house, the shades were drawn against the summer heat. In winter they were thrown open to the bird feeders. Beaded curtains—God’s tears, Mimi thought—marked the entrance to the study where the German lesson was held. Mimi felt a kind of spiritual tingle when the beads cascaded over her, or lingered on her lips or hair. Helen had given each of the girls a tiny shimmering notebook in which they copied out the verbs and nouns they encountered in fairy tales. Mimi’s was an aquatic green, reflective as a mirror that she could beam into her teacher’s face and watch the light dance across her cheek. It was not garish but somehow refined. In the tiny notebook the girls scribbled nouns along with their articles: das Haus, der Bahnhof, die Strasse. Mimi was fascinated by the smallness of the notebook; it’s being hers; the effect of the cover, at once glossy and matte, impenetrable yet incandescent.

Hypnotically Mimi moved the cover under the light, the calm voice of the German teacher filling the cramped book-lined room with words from the Brothers Grimm. Her notebook was a shimmering underwater kingdom. Mimi was pulled into a deep sea of animals that floated past in slow motion like the ray, with its undulating body and perfect forward momentum. The lesson room at dusk was a pocket of stillness, a refuge like the one turned-down page between the covers of a book. Helen slowly turned the pages of the picture book and read aloud in her soft, calming voice.

Here was something interesting. Mimi could create a loop through which a single hair could be pulled: threading the needle. She could rub several hairs flat: waxing the thread. She could force the hairs to merge: tying the knot. And she could cause a single hair to snap: breaking the thread of thought. Her fingers were nimble as that of an expert angler. The trick was to yank just hard enough to produce a satisfactory pop, but not so loud as to cause others to fret about split ends. One thing that was good about the German teacher was that she ignored Mimi’s single-minded harassing of her hair; ignored the extraneous punctuation. It helped Mimi to learn better, much better than her sister who had to be reminded to change the article of her masculine direct object in the accusative case. At times, Charlotte asked her mother to be excused from the German lesson; Mimi said she would stay home too. Charlotte said, in so many words, that she served mainly as a backdrop to her sister’s brilliance, a foil to reflect her shine. At the same time she was protective of the younger. Perhaps she sensed that being pegged the smarter one was of no great avail and certainly conferred no advantage in getting a hamburger. Charlotte ate every hamburger offered her and was rounder than Mimi, who could not be relied on to take a simple bribe.

Mimi rubbed a lock of hair between her fingers. Always, between knots, loomed fear and redundant hair. She never meant to cause knots, which sometimes had to be cut out with scissors. She meant only to hold things as they were, to allay this premonition and fear of growing up and coming fully formed into the world. She meant only to make the private thft-thft-thft sound and to feel this pleasure of the fingers and the scalp, all the more pleasurable for being constant and reassuring, and above all, under her control.

But there was something private, intimate, and therefore obscene about her motions, like the blind, deaf, and mute child of her father’s colleague with whom he made her play some weekends when the girl came home from the institution. The girl rocked back and forth to stimulate herself sexually, the colleague explained apologetically, to compensate for a lack of sensation. Mimi was surprised the colleague had told her this, for she never would have guessed anything so lurid on her own.

Mimi’s hair twisting was a kind of deformation too. Last month, Mimi had fallen asleep in the back of the blue bus and absently twisted an entire battalion of toy soldiers into her hair. Pinioned to her scalp, firing in every direction, they looked like jungle commandoes or crazed deserters; Gertrud was horrified. “Wouldn’t you like to have nice, long, beautiful hair?” she asked. At home, Gertrud stripped Mimi naked, plunked her on a pile of newspapers, and shaved her head with dog clippers. It was a misunderstanding. Mimi had reckoned on new, long hair instantly, but when Gertrud stood her up on the bathroom sink—at eye level with the mirror, for Mimi was petite for her age—there was no lustrous, flowing mane, just a picked-clean scalp bobbing on a naked shivering body. Mimi bawled for days, and kept reaching for her phantom hair. Gertrud too looked crestfallen. It was she who suggested Mimi had misunderstood: she hadn’t meant the hair would grow back instantly.

Mimi got a special dispensation to wear a hat to school, and insisted on choosing it herself: the green wool ski cap Olive had knitted for her last winter. Gertrud didn’t say anything—maybe she felt guilty about having imposed her will on what turned out to be a surprisingly unsuspecting child, for all her smarts—but it was July and Mimi sweltered in the summer heat. Of course it was only a matter of time before the mean boy—the same one who had built a wooden castle around the class guinea pig only to topple the blocks when no one was looking and strike it dead—ripped the hat from her head and flung it across the room, and everyone laughed, pointing, in a circle around her.

Her hair did grow back, Gertrud was right. It looked no different than before, however, and was soon shaggy and jagged from her uncontrollable twisting. After that, though, everyone left her alone. Every other week or so, Gertrud swept up a pile of knots from behind the sofa, where Mimi, engrossed in reading, dropped them. Gertrud even placed one in her keepsake drawer.

Helen held up a German alphabet book. She pointed out an apple: der Apfel; a boat: das Boot. Mimi imagined neuter beings as dwarves with stout trunks and long limbs. Her sock-monkey doll, for example, now in repose on Dwight’s swivel chair, looked suspiciously like a neuter being. “That monkey does not talk,” her father would say when he was tired of being contradicted for the hundredth time by the monkey. Yet apropos of nothing, he sometimes directed comments at the monkey, avenging Mimi’s conception that the beast was at least a neuter being. As everyone knew, neuters maintained an affable silence. Except, occasionally, for girls (das Mädchen), who were neuter beings too.

Mimi was always surprised by the clang of the doorbell at the end of the German lesson. Time had evaporated to form beads of rain that lashed against the windows. Mimi knew the rain would go back to the ocean, which would eventually form rain clouds and later, more rain. The undersea figures of the fairy tales would remain untouched, because they inhabited the depths of the ocean and because they were not real. The cycle of rain was endless, as time too was circular, but time, it spiraled like a tornado, always up, up, growing up. Mimi’s tears streaked down her face, like the rivulets of water on the window. She cried not for the rain, but for the tornado of time that would wrench her from this place. Charlotte glanced at Mimi, who held, white-knuckled, to the table, waiting for the inevitable: Helen would rise, calm as the eye of the tornado, and answer the door to Gertrud, who would breach the beaded teardrop curtain, and, finger by finger, pry her child loose.

* *

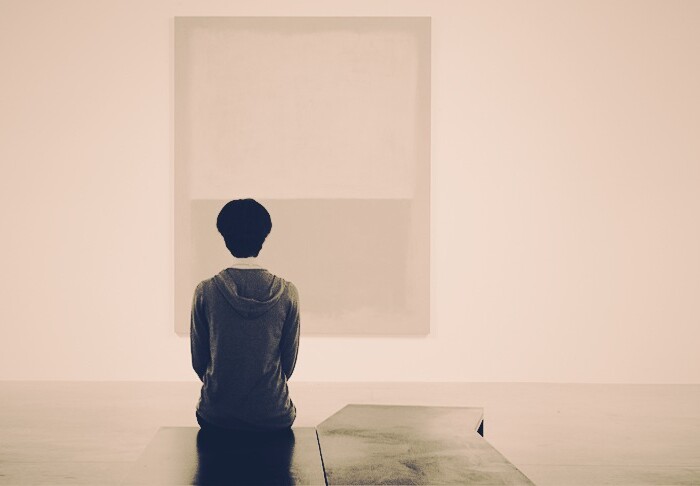

Image: “Shy Zebra” (2011) by Ruby Palmer

[ + bar ]

Lions

Iosi Havilio translated by Andrea Rosenberg

And in the middle of the day came the night . . . Down the hill, all made of shadows, the Protagonist... Read More »

Kondenswasser

Anja Kampmann

Versuch über das Meer

Es soll um den Horizont gehen den

Farbauftrag der Ferne das helle Knistern

der Flächen von Licht und die Verbreitung

des Lichts wie es... Read More »

The Red and the Black

María Gainza translated by Jane Brodie

I’m scared. I’m sitting on a plastic chair waiting to see the doctor. It’s a cold spring morning and I’ve come... Read More »

Ukrainian Tales of Buenos Aires

Stanley Bill

In the late 1920s somebody shot and killed a Ukrainian railway worker named Mykhaylo Marusiak on a street in Buenos Aires. The date is unknown. The... Read More »

sending...

sending...