Everything Good That I Know I Learned from Women

Tryno Maldonado

translated by Janet Hendrickson

1

My mother is a teacher. A preschool teacher. If you want to fuck up a man’s amorous relationships with women for the rest of his life, there’s no more efficient method than this: sign him up for his mother’s preschool class. Good luck, Freud! With time I’ve developed the belief that my relationships with women are nothing but one emulation after another of this, my platonic and stormy relationship with my preschool teacher. Who happened to be my mother. The same longings, the same idealizations, the same expectations. The same scenes of jealousy. The same mistakes. Ah, Freud… One day, when I was six, my mother caught me masturbating with a pair of her underwear that she’d hung to dry in the shower. I was accused. That afternoon my grandmother Amparo told me I would burn in hell for being a pig, and she put out the embers of her cigar on the back of my hand as a taste of what was reserved for me there. Freud… I shit on Freud!

2

My grandmother Amparo liked to smoke cigars in the afternoon while she crocheted and gossiped with her daughters-in-law. They drank very weak black coffee in pewter cups and smoked. Sometimes, and only if my grandfather wasn’t there, my grandmother secretly poured a little stream of mescal in her coffee and theirs. I never understood why these women, my aunts, laughed so much and so loudly. You could hear them laughing as far as the corner store where they would send me to buy more cigars. One day I secretly drank my grandmother’s coffee. I dipped a finger in every so often and stuck it in my mouth without her or my aunts noticing. That day I couldn’t stop laughing with them, either.

3

My mother liked to invent words. Or perhaps she had learned them from her mother who, in turn, had heard them at the ranch where she was born. I don’t know. For example, my mother would tell me and my brothers that we’d “regurbled” the change or some arithmetic operation. When what she wanted to say was that we’d gotten “confused” or simply, that we were wrong. Don’t regurble it, she’d say. You write cat with a c, not a k. There were others of her own vintage, naturally. Chucitos. That’s what she called me and my brothers. According to her, I was a mix between Chucky, the diabolical doll, and Bruce Lee. Bruce Lee was my idol at the time, my role model. I would imitate his flying kicks, the ones he used to defeat Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, only I applied them against my brothers’ teeth. Bruce Lee. Chucky. Chu-cee. Chu-ci. Diminutive: Chucito. My mother. That’s what she was like. When our father would beat us with copper wire across the ass and thighs for getting into mischief, our mother (though she was on our father’s side at first) came to console us. Chucitos! she would say. And invariably, she drew a hesitant smile from the tears, a smile that immediately turned into laughter. Chucitos! And my brothers and I would laugh again.

4

I have several scars on my hands, like calluses, from burns. My grandmother Amparo gave them to me with her lit cigar every time my mother, driven to despair, went to tell her I’d been suspended from elementary school again for masturbating in class. Show me the hand you did it with, my grandmother Amparo would say, and she’d draw the lit cigar near. You’re not going to heaven, she would say. I understood: You’re going to be my ash bin.

5

I remember several of the many scenes of jealousy that wore my mother out when I was her preschool student. Certain perks, privileges came with being the teacher’s son. Also, I enjoyed academic impunity, since I was the most advanced student in class. (My mother’s sister, an elementary school teacher, had taught me to read and write a while before.) I bestowed cruel nicknames on the children whom my mother spent more time with than me, especially children with physical defects or who were particularly stupid. Like Doctor Celebrum (not Cerebrum.) Doctor Celebrum was a boy with Down syndrome who was in our class because special education schools didn’t exist in our town. Or Golden Feet, a boy with legs crippled by polio who had to use orthopedic braces to walk, with great difficulty, and who I tortured, making him chase the soccer ball at recess. I didn’t reduce my level of low-intensity terrorism against those brats who passed for my mother’s bastard children until their parents came to complain to the teacher (that is, my mother). I stole things in revenge from the richest kids, grocers’ and teachers’ kids, if my mother put a little star on their foreheads or took a picture with them at school festivals. Expensive crayons, glue in containers with blue elephants, play dough in brightly colored canisters, scented erasers… All of the prettiest and most expensive things in the classroom invariably ended in my backpack. That is, in the backpack of the teacher’s exemplary son. Those who didn’t pay tribute knew that they risked being branded the whole year with the worst nicknames or would find me urinating on them or chopping off their hair. I would sabotage festivals if I saw my mother looked pleased with this or that child’s talent for, let’s say, singing without changing the words or banging on the tambourine without fucking up too much. I had to stand behind everyone else during presentations because of my height, so I’d push the kid with the tambourine or whoever was in front of me as hard as I could; then I’d take off my shepherd’s serape and the stupid straw sombrero from the play and trample them on stage. All, of course, to get the attention of the teacher (who was my mother). Sometimes, while the rest of the children stupidly traced pages of colored circles with crayons, I would go to a corner and masturbate until my mother (that is, the teacher) came over to forbid it.

6

My grandmother Amparo was from the ranch. She and her family experienced the Revolution in Zacatecas first hand. The Revolution. An age of barbarians from the north that, to my childish mind, explained why my grandfather carried a pistol on his belt and why my grandmother could spit more swear words than anyone else this side of the hemisphere into the eyes of the first poor devil to cross her. She let out more profanity than her thirteen sons and my grandfather combined. Her wide arsenal of insults never ceased to surprise me. Some seemed so clever I’d repeat them at school without even knowing what they meant. They made me invincible. But anytime my mother caught me repeating the shit I learned from my grandmother, she’d force me to swallow a handful of dish soap and plug my nose until it all went down. My cousins, my brothers, and I all knew it was best not to make our grandmother upset. One peso short when she sent us to the corner store, an order poorly carried out, and there it was. You risked her loosing her whole battery of slander on you like insecticide on an insect. She almost never hit us, and sometimes she would even cover up for us or intercede with our grandfather on our behalf. Our grandfather would break out the leather belt at the least provocation. He’d soak it in water, order us to drop our pants to our knees, and flog us. It hurt to the bone. For days my cousins and I would be left with deep red stripes crisscrossing our asses and thighs. A week would pass before we could sit down again. But after a few days, like outlaws hardened by the punishment, we would fall back into the illegality. My grandmother, however, could trample you, could kill your ridiculous, insignificant child’s soul forever with two or three venomous words. I would double over laughing when I heard her tell someone else, “Go to hell.” Although what I understood was, “Go to smell.” My grandmother would say: “That son-of-a-bitch asshole isn’t worth shit.” And I understood: “That sandwich tadpole ate a banana split.” My grandmother, furious, would shout: “Go fuck your mother.” And I understood: “Good luck, brother.”

7

Once she got everyone in class together. My mother (that is, the teacher) had us get in line and we went out to the playground. There’s a boy in this school who is sick, said the principal over the microphone only used on Mondays for the flag ceremony. It’s a very contagious disease, she said. This sick boy likes to touch his private parts in front of other boys and girls. We’re going to have to suspend him so he doesn’t infect his classmates. That’s what the principal said, and for whatever reason, I enjoyed two weeks of vacation, starting that day.

8

I’ve been a strange case since I was a boy. That’s what the preschool principal said when I saw her again a little while ago. Strange. From the Latin extraneus, from the exterior, an alien, a foreigner, odd. I stopped by the preschool to pick up my brother’s son, and I asked the principal if she remembered me. She made a gesture of horror. She practically crossed herself. I was a very odd child, and they didn’t know what to do with me anymore. That’s what she said. I didn’t talk to other kids except to call them names or threaten them. I didn’t socialize at recess. And when there was a field trip, I would plunk down in a corner with my arms crossed, and no one (not the principal, not the gym teacher, not the President of the Republic) could move me from that spot. I would spend the day sitting in silence, waiting for the group to return. When they came back from their outing, they nearly always found me with my uniform pants and socks wet. My pride wouldn’t let me move, not even to use the bathroom. However, my grades allowed me to enter the preschool color guard, and I consented for one reason: the flag bearer, a dark, skinny girl, wore little white leather boots for the ceremony, boots that were new and very cute. On flag ceremony days, in the afternoon, when my mother and I went home, I liked to lay face down on the back seat of the Volkswagen and rub my groin against the foam, thinking of the flag bearer’s little white boots.

9

My grandparents’ street, where my cousins and I spent our childhood, appears in a Cormac McCarthy novel. The street McCarthy’s cowboys traversed was the street where we hunted rats with slingshots and played soccer. Once, one of my grandmother’s neighbors, with whom I think she’d had a falling out, came and knocked on the door. She looked angry. I was the one who got the door. I’d left class early, and my grandmother’s house was a few blocks from the elementary school. The neighbor had come to complain to me. She screamed a lot and waved her arms. My grandmother came to defend me from her hysteria. They exchanged words. Apparently one of my grandmother’s sons had done something very bad to one of the neighbor’s daughters. I didn’t understand very well, but it was clear that one of my twelve uncles had done something serious. Or even my father. I went to hide behind my grandmother Amparo’s skirts. Tell your son not to go after my daughter again. Which of my thirteen sons, ma’am? my grandmother said. Well, which one do you think. The biggest drunk of all. It would be my pleasure, ma’am, my grandmother said. But tell your daughter to be careful when she goes out. Which of my daughters? the neighbor said. Well, which one do you think. The biggest slut.

10

I never dared to talk to the girl who was the preschool flag bearer. I can’t say I liked her face or that I was in love with her. I don’t remember what she was like. From the very first day I came to the conclusion that what drove me crazy me about her, what made me anxious and kept me up at night, was the contemplation of those little white leather boots that came up to her knees. An ungovernable fever made me want to rub my groin against just about any smooth surface at all times. It was like a disease. My parents even took me to the doctor, hoping that my problem had a cure. But no. My mother didn’t know what to do with me. My grandmother Amparo gave me a cleanse with herbs and a rotten egg and had a mass said. Nothing. I masturbated in school. I masturbated in the bathroom. I masturbated in bed. I masturbated in the car. I masturbated on the street. I masturbated through the fifth and sixth innings of baseball games under the mitt. I masturbated in church on Sundays. I even masturbated in my sleep. I was a precocious hand job champion! There were literally days when I didn’t go down to eat so as not to deprive myself of the pleasure of rubbing my groin against the mattress, imagining the little white leather boots of the girl who held the flag with the eagle and the serpent. Never again in my life have I experienced a period of such fervent patriotism. When my grandmother learned about my hobby of jerking off, she burned my hand with the tip of her cigar and repeated the dispatch to hell. What did hell matter, if I could bring the memory of those leather boots with me, so white and new, marking the way!

11

Why didn’t my mother have eyes for me in class, that pretty twenty-nine-year-old all the other students fell in love with, who demanded her attention, screaming? She became another person the moment she crossed the classroom door. Such coldness! I wanted to break my head against the wall from jealousy. For example, there was a smart boy. He was a white boy from a rich family who hoarded my mother’s attention during class. His parents brought us a piñata for his birthday. An expensive piñata, one of those pretty suckers you don’t dare touch so it doesn’t go to waste. I was taller than all the other students. At kids’ parties (except at my cousins’, who were the same height as me or taller), I was always last in line to hit the piñata. Plus, I played baseball. I was famous for the threat my destructive power held against the national production of piñatas per capita. The birthday of the rich white boy, my mother’s (that is, the teacher’s) favorite, would be no exception, of course. The piñata had suffered a few feeble hits from other children and had lost a little arm or a leg. And there I went, last at bat, building momentum as if I were really in the batter’s cage. The other children formed a circle around me and sang and cheered for the piñata to break. But the commotion, the disorder, the uproar that broke out after the first hit exceeded my plans. My mother and the other teachers rushed to pick up the rich boy with the broken nose and take him to the hospital. They screamed and gestured hysterically. His preschool uniform was covered with blood. It seemed incredible that such a small, fragile, delicate creature could produce such quantities of blood. My mother held his head over her thighs before they took him. The boy’s blood stained her smock as she desperately tried to stop the hemorrhage, without success. I ran to hide in the school bathrooms, the piñata stick still in my hands, enervated by the contradictory feelings of resentment at seeing my mother hold the bloody face of her favorite student over her legs and the secret pleasure of having killed (at that moment I believed I had killed) the bastard child who was neither her son nor me, a morbid sensation like a drug that I’ve rarely experienced since. Except for a couple years later, when I ripped off a piece of my brother’s ear.

12

The day my grandmother Amparo died, I refused to go to her funeral. My mother dressed me and my brothers in the best clothes we had (which she had bought secondhand and which I would hand down to my two younger brothers when they didn’t fit me anymore.) She ran a comb with lime juice over our heads until our hair was like soup. My parents and brothers got into the Volkswagen. But I didn’t want to. We were already running late. When my father, furious, came to see where I had hidden, he found me in bed under the sheets, my hair messed up, undressed. Get dressed and get in the car with your brothers if you don’t want the mother of all beatings, he said, raising his fist. That was what my father said when he was most irate. The mother of all beatings. And I obeyed because I imagined my mother, beaten and broken like a plastic figurine that fell to the floor and shattered into a thousand little pieces and made me feel like crying. Go to smell, I said, furious. My father couldn’t believe his ears. What did you say? Just go to smell, I said. When he came to his senses after the atypical response to his command (the first act of rebellion in his house), he clenched his teeth and pulled me out of bed by my hair and gave me the worst beating of his life. He hit me hard, the way I had seen him hit other adults his weight and size when they started fights at soccer games. Go to smell, I said again, between sobs. This time, my father didn’t even look at me. He left the room, slamming the door. Then I heard my mother start the engine and the sound disappearing down the street. The whole house was silent. I was flooded with a mix of rage, impotence, and desolation, knowing that my family had left without me. They would honor the obligations that corresponded to the son, daughter-in-law, and grandsons they were. Which, by contrast, made me a swine, not only in the eyes of my family, but the world. A son of a bitch, my grandmother would say. What I felt was rage and hatred directed, above all, at myself for the terrible offense I was giving my grandmother. Not only by failing in my duty as a grandson at her funeral, but because for all the effort I made, I couldn’t feel sad or pretend to feel sad at her death. I swear I tried. I tried with all my might. It was my first encounter with death, and the truth was that now that I was so close to death, it didn’t matter. What kind of person was I? Maybe the preschool principal was referring to that when she said I was a strange boy. I was a monster. A stranger. Extraneus. An alien who contemplated human experience from the exterior. That was what I thought then, at six years old, and I couldn’t get rid of that image of myself, a freak, for a very long time. I had believed that when someone in my family died, the day would be very sad. There would be thunder and lightning and it would very probably rain, and I would go crazy before the coffin with grief. But none of that happened. That afternoon I watched Mazinger Z, my favorite cartoon, without the least remorse, despite my mother’s explicit ban on TV for the period of mourning. I felt miserable because I didn’t experience the biblical pain that I thought would split me from head to tailbone like a bolt of lightning. I would be the only one from the immense brood of grandchildren to deny my grandmother one last gesture of gratitude, the so-called last farewell. I remained on the floor where my father had left me and cried, thinking about how ignominiously selfish I was, about how I was a terrible kind of human being, since unlike my many cousins and unlike my two brothers, I didn’t feel sad at my father’s mother’s death, I was a terrible kind of human being because I didn’t feel sad at my grandmother’s death.

13

The day of the incident of the piñata and the rich boy’s broken nose, I found my mother crying in the bathroom at home. Apparently the principal had reprimanded her severely. The rich boy was the son of an alderman from the PRI, the party in power at the time, and from then on things got darker for my mother. Because of me. But I had no way of knowing, much less of understanding. They suspended my mother. Not only that. She had to change districts because of the incident with the PRI alderman’s son. In punishment, she was transferred to a preschool outside the capital. My mother worked in the outlying town where she was sent in retaliation for the rest of the days of her professional life, until her retirement. That is, for more than thirty years. Only the intervention of the teachers’ union (also connected with the PRI) kept my mother from being fired just like that. My mother never punished me for the incident of the boy with the broken nose. It was as if nothing ever happened. We never talked about it again. Neither then nor now that I’m older than she was at the time. The day of the incident of the boy with the broken nose, I woke up at midnight. I had heard noises on the first floor of the house, a tiny, two-bedroom public housing affair, where privacy between the five members of our family was impossible to maintain. I left the room with the one bed I shared with my two brothers and went to the bathroom. The noise I heard was my mother sobbing. She cried disconsolately, sitting on the closed toilet seat. She had forgotten to shut the door. My mother gave a start when she saw me but recovered right away. You’re not supposed to be awake, she said. Her eyes looked like eggplants from crying so much. I have something to tell you, I said. You can’t sleep? she said. I can, I said. Well? Chucita, I said. Chucita, I said again, like an incantation. Chucita. And for the first time in a very long time, I saw my mother smile.

* *

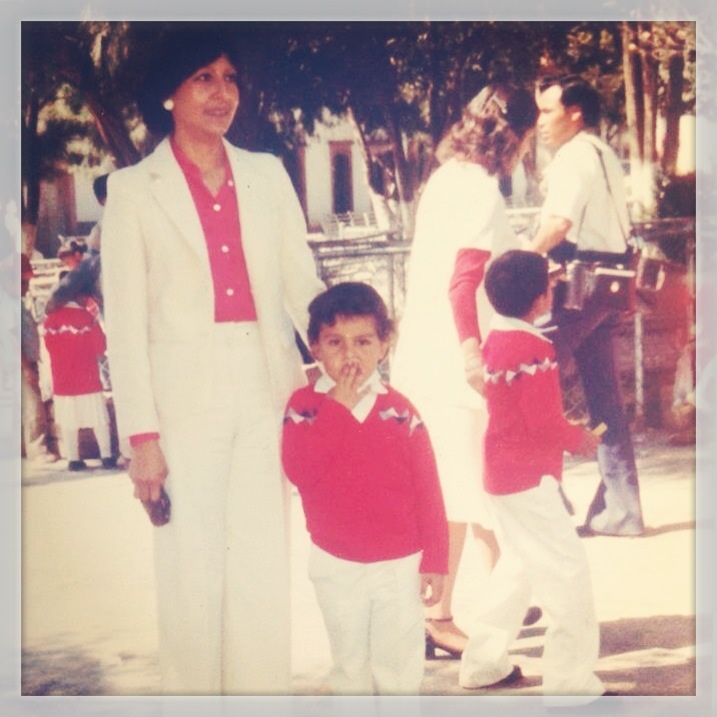

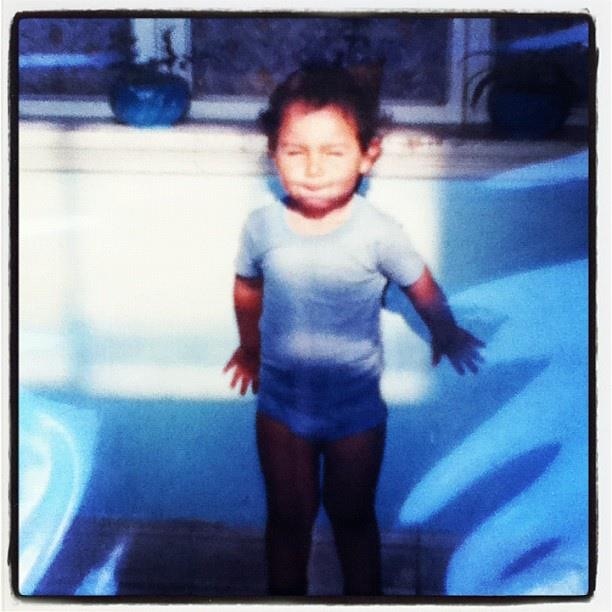

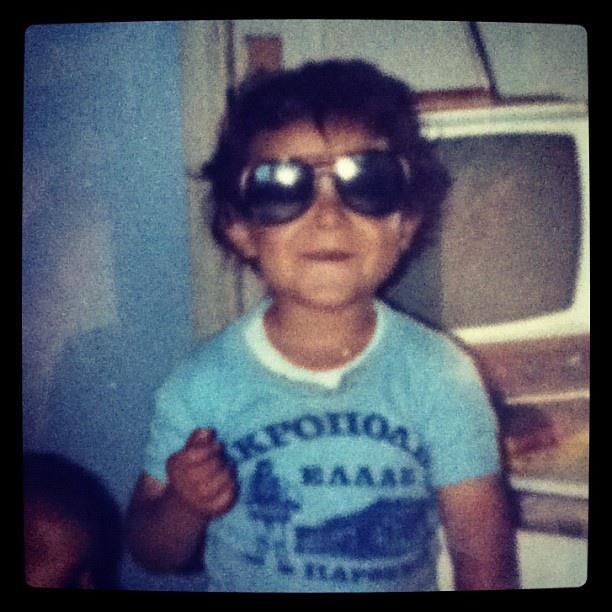

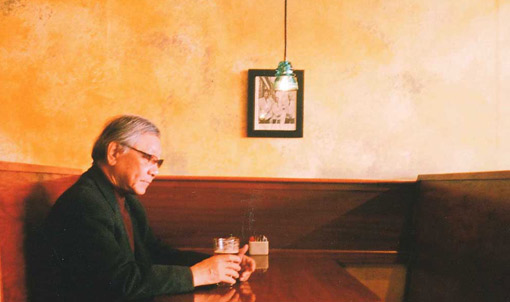

Images: Tryno Maldonado

[ + bar ]

A Mistake

Zheng Chouyu translated by Qiaomei Tang

I traveled through the South Land A longing face blooms and fades like the lotus flower with the seasons The east wind is... Read More »

Hegira

Adam Morris

Slakers shambled along the coasts, the brine in the breeze searing nostrils, lashing cheekbones and the edges of eyelids, whittling parts of faces to... Read More »

Ariel Schettini

translated by John Oliver Simon

SHADE SAILS

Not poppy, nor mandragora, nor all the drowsy syrups of the world, Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep Which thou... Read More »

The Marquise was Never Content to Stay at Home

Sergio Pitol translated by George Henson

For Margo Glantz

A feeling of disaster is haunting the world. The novel records it and, in doing so, is resplendent. The more rotten... Read More »

sending...

sending...