I’ve Lost Everything I Loved (excerpt)

from J’ai perdu tout ce que j’aimais by Sacha Sperling

translated by Addie Leak

I had decided that my name would be Sacha Sperling and that my life would be dazzling and spectacular.

I’d understood that the only way to exist was to become someone else.

I’d written a book.

The book was a success.

It was translated into languages I didn’t speak.

For two years, the foreign versions accumulated in my bookcase. My face was on some; on others, young Asian boys in suggestive poses. Most of the covers looked like the anti-tobacco posters stuck to the walls of school infirmaries.

The book was simple. It was a bunch of scenes telling the story of a lost teenager in love with his best friend. A fourteen-year-old boy almost mechanically recounting the dissolute lives of his little band. The book included passages later described as “off-putting,” “pulp,” or “hyper-violent.” (A chapter describing a thirteen-year-old girl at the heart of a three-way had particularly marked readers. Then there was the palace suite orgy, the weekend at Eurodisney on Xanax, a conversation about a man who was set on fire, etc.) It was the picture of lobotomized youth, passive and ecstatic. The portrait of blasé kids during the Sarko years, wandering from fast food joint to fast food joint, from easy pleasures to fast ones, in a sort of semi-coma. In the space of just fifteen minutes (I should say for fifteen minutes), I’d become a small-time literary star. In the space of just fifteen minutes, I found myself living my dream. Everyone wanted to meet me, to interview me. There were pictures of me in jeans in Elle, in a torn t-shirt in Le Grand Journal, wearing my Nikes in L’Express. The titles of the articles were “Hello, Melancholy” or “Monstrous Sacha.” There were pictures of me and my super-cool friends, at my super-cool party, in the super-cool swimming pool of the Hôtel Costes, filmed by the super-cool program Paris Dernière. They asked me questions on the phone, in cafes. And I said things like, “It’s an extraordinary opportunity,” or “It’s an incredible luxury to be able to write.” I was constantly repeating stupid shit like that. Today, I can think of a thousand other phrases just as insincere but much more original. At the time, I wasn’t trying to be original. At the time, I just wanted to “continue to have the chance to meet interesting people.” I’d written all these things that were so shocking, so vulgar, and my responses were so clean and neat that they threw the reader off the scent. The truth is that I didn’t give a damn about the questions or the answers. I was simply fascinated by the noxious golden vapor that seemed to float in the wake of my seduction.

That’s how I became your little sister’s favorite writer.

I remember my editor: “Do you realize, Sacha—they’re ordering a thousand a day!”

“And is that a lot?”

I’d decided that my name would be Sacha Sperling, that my life would be dazzling and spectacular. I made this decision between two mouthfuls of orange juice. One morning, I decided to change my name, and then I went to brush my teeth.

I was eighteen and looked thirteen.

I’d decided that I had to become someone, and fast. I had to exist. Because on one hand were the complications of childhood, shadow, and frustration, and on the other, an infinity of illuminated paths. Street lamps, stars, it didn’t matter… There was something that looked like light. On one hand, endless waiting; on the other, all these people ready to love me.

But after a while, my life was neither dazzling nor spectacular. After a while, the lights went out and there was no longer anybody there to love me. In the blink of an eye, only the journalists and talk show hosts were left, as intrigued, annoyed, or aggressive as I had been in my book, and their interest seemed more and more like contempt. Because in addition to the stories of parties, above and beyond the laundry list of illicit substances, what put readers off was the profound apathy with which the book’s narrator seemed to watch the world burn around him. How could he witness all that without reacting? How could he be so young? That was what they started to reproach me for. As if I’d exaggerated. As if I were laying it on too thick. But when you’re eighteen, you don’t choose to reveal yourself. I was far too young to recognize the immodesty necessary to write. I had no filter. That’s why there was something terrifyingly sincere in the book that excited teenage girls and frightened their parents. On Monday, I was a promising writer; on Wednesday, the idiot puppet of a publicity coup; by Friday it didn’t matter anymore because the book was selling and that was the only thing that never changed, week after week.

For more than a year, they had a photo of me in the Virgin megastore. From the Champs-Élysées, you could see my head inside the store. Eyes that seemed to look you right in the stomach. The poster stayed there for what seemed to me an abnormally long time. Nothing justified it staying there that long. I think the Virgin employees just forgot to take it down. So every time I walked between Monoprix and Quiksilver, I passed Sacha Sperling, and his look said, “This is it, we’ve made it! We exist! That’s what we wanted. Look how bright the path is now. You achieved your dream, dammit, look at us! Come on, don’t screw it up by being moody. You wanted your mug blown up for a photo, well here it is! Order up, buddy!”

And I looked at this rather cute, slightly unpleasant guy with his little smirk. And every time I passed him, he smiled at me. And the more I looked at him, the more the smile scared me. Because it wasn’t mine. It wasn’t me anymore in the photo. It was him. He was the happy one who didn’t want this to end. He was the one who looked like a sated beast. The invisible little boy, made up as an adult, nasty as a kid the day after Christmas. I’d wanted my slice of eternity, the photo of my face blown up, and yet it was his that I saw on the poster. I wasn’t there anymore. In the driver’s seat, an ambitious young man yelled at me to open my eyes. He was saying, “No matter what, don’t stop. No matter what, remember you’re happy, that this is what you want.” But that voice was weaker and weaker, dreamlike, as far away as childhood. I started by scorning that voice, and I finished by completely ignoring it. I was going 200 km/hr in a blazing new muscle car, gleaming, loud, all in the body and nothing in the motor, and I wanted to throw myself out of the car. They talked about Sagan. Sagan, set in the paint and golden dust. Sagan so alone. The phantom that everybody comes across without ever seeing. And me, little Sacha Sperling, nobody, unwitting ersatz, splinter of media quartz. “You’re very Beigbeder, very Ellis, very Minou Drouet, very Minnie Mouse. Have you read Death in Venice? Larry Clark? Is this raincoat a tip of the hat to Houellebecq? Does your haircut look like Zeller’s? Are you gay? Is this a genre? What’s your lucky accessory? Your favorite book? WHO ARE YOU?”

It reeked of sulphur. I had the right face, the right book. The winning horse. Royal flush. And I couldn’t take it anymore.

I’d understood that the only way for me to exist was to become someone else.

I’d written a book.

The book was a success.

It was translated into languages that I didn’t speak.

One day, they took down the poster at the Virgin megastore. One day, I passed by the enormous doors of that old bank, and my photo was gone.

Sacha Sperling wasn’t looking at me anymore.

He had… disappeared.

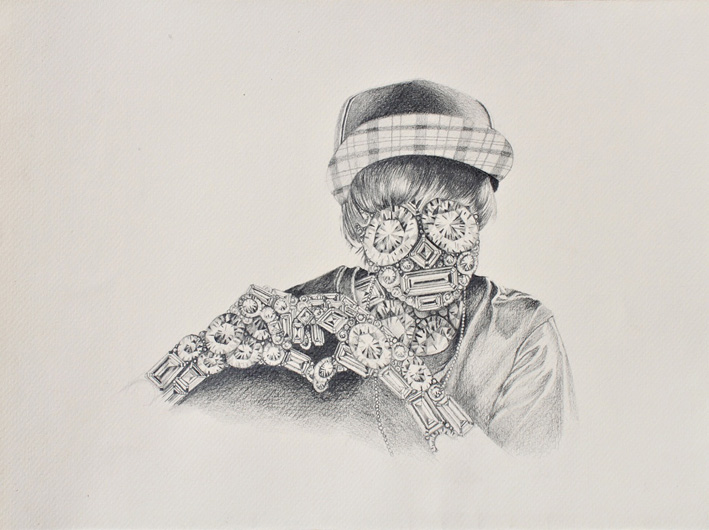

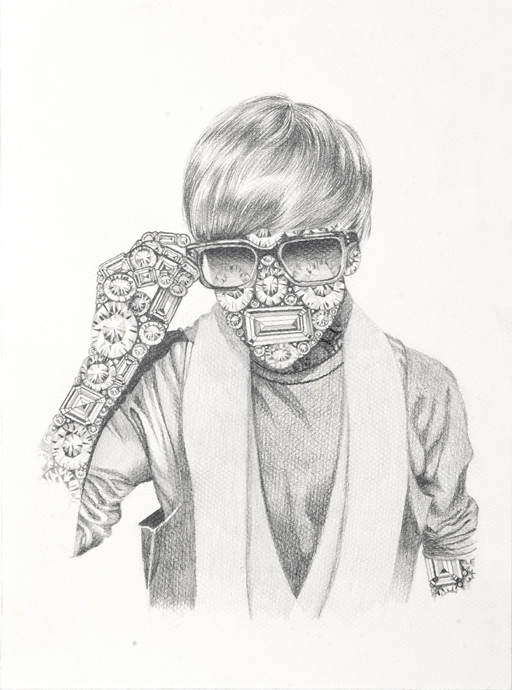

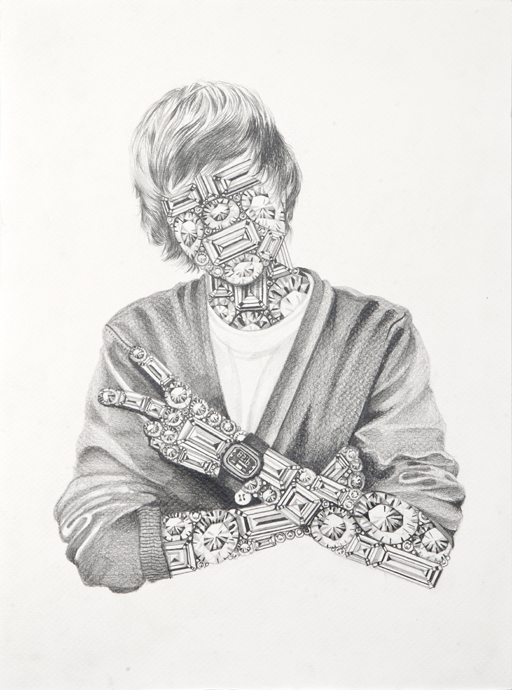

Artwork: Luciana Rondolini “Justin” (2012), courtesy of miau miau

[ + bar ]

Zanzibar: an excerpt

Thibault de Montaigu translated by Lara Vergnaud

Some people will no doubt feel this work lacks precision and that it’s impossible to write a decent book about a criminal... Read More »

Orellana [valparaíso]

Álvaro Bisama translated by Julia Ostmann

My favorite bookstore is a ghost bookstore. It was called the Orellana and was located in the center of Valparaíso. It closed a... Read More »

A Love Story

Bernardo Carvalho translated by Max Seawright

1.

He haggles over fish at the wharf. He’s done it since before his tenth birthday. His mother makes him. It’s no accident he... Read More »

The images featured in BAR(2) were selected by Marisa Espínola and appear courtesy of:

Espacio en Blanco www.espacioenblancocultural.org

Espacio en Blanco began in Buenos Aires in 2009, when writer Francisco Moulia and... Read More »

![Orellana [valparaíso]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/la-foto-crop-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...