On Translating a Translation

Adam Z. Levy

For all the theories of translation one disavows or keeps tacked above the bed, there remain certain unscientific gut-level questions like: Have I gone too far? Have I gone far enough? During the year that I spent working on Hungarian writer Gábor Schein’s first novel, The Book of Mordechai, I approached my author often with such questions. We met on Friday evenings to drink fizzy lemonades at an outdoor café in the Budapest district where we both lived. If it is possible to condense a year’s worth of meetings in a single phrase, it might be most fitting to call them dry interrogations: I pointed to places, in my own text and in the original, and asked whether I had understood the implications of this word or that phrase. It is one of the privileges of working with a living writer to be able to ask even the most trivial things.

Schein, whose second novel, Lazarus!, was translated by Ottilie Mulzet for Triton in 2010, puts his formal inventiveness on display in The Book of Mordechai: it is a retelling of the biblical Book of Esther, woven into the story of three generations of a twentieth-century Hungarian family. The narrative shifts in time and place from paragraph to paragraph and is filled with anecdotes, family reminiscences, source documents, and meta-narratives on translation that defy easy classification. It is as much about a country’s—and a family’s—difficult history as it is about the limits of language in preserving the memory of it.

At the novel’s center, though in many ways it has more than one, is a young boy named P. who spends the summer learning to read and write under the supervision of his grandmother. The text his grandmother has him read is the Book of Esther. She brings out an old yellowing edition that belonged to his mother, and which was translated at the beginning of the last century by Leopold Blumenfeld, a rabbi from the town where she, P.’s grandmother, was raised. (The Blumenfeld translation is an invention of Schein’s, based on an edition of the Book of Esther that Schein produced at one of our meetings; its translation credits belong to the very real Mór Schwarz.) Blumenfeld’s translation, the one presented in The Book of Mordechai, raises questions about where we draw the line between translation and interpretation: the reader learns early on that “in certain places [he] changed the text”—in one instance, by “arranging the letters of the Hebrew text from an unquestionably hard-to-understand sentence in a way that departed from the original, namely by inserting one letter, a surprising but seemingly-correct reading was attained.”

For Blumenfeld, the manipulation of the text is fact an attempt to stabilize it: his amended version flows—to borrow Péter Pázmány’s phrase from three centuries before—“fluidly, as though it had first been written by a Hungarian, in Hungarian.” Something similar happens when Blumenfeld replaces the stake on which Haman hopes to impale his rival Mordechai with a tree, so as to have him hanged. Blumenfeld goes one step further, changing the unit of measurement in the text from cubits to ell, in effect doubling the height of the tree. With the new measurements, we are told a hanging would have been impossible. The already fable-like tale is taken from the exaggerated to the absurd, since the hanging still takes place. In Schein’s vision of the book, it is necessary that it does: a translation cannot outrun the shadow of its source.

Blumenfeld’s translation of The Book of Esther poses subtler difficulties as well. There are many more modifications to the Schwarz translation than Blumenfeld (or Schein) lets on. Words are omitted or replaced with more modern equivalents; the tone of entire lines is amplified or dampened, leaving their translator to navigate between four texts rather than two. For example:

In the English translation of the Hebrew bible that I used, a section from Esther reads: “Some time afterward, when the anger of King Ahasuerus subsided, he thought of Vashti and what she had done and what had been decreed against her. The king’s servants who attended him said, ‘Let beautiful young virgins be sought out for Your Majesty.’”

The Blumenfeld translation reads: “When King Ahasuerus’ anger subsided, he thought of Vashti. He was reminded of the pleasantness of her touch, the pleasantness of her voice. But the king’s servants said, ‘Let beautiful virgins be sought out for Your Majesty.’” Most notable is Blumenfeld’s insertion of the second sentence: “He was reminded of the pleasantness of her touch, the pleasantness of her voice.” It replaces the juridical with the sentimental, allowing the buffoonish king a moment of nostalgic self-reflection not present in the original: he recognizes what he has lost and what he will not be able to bring back. The tone has also changed as a result: the formality is softened as “the king’s servants who attended him” becomes the more colloquial “the king’s servants.”

In order to match the register of Blumenfeld’s translation I tried to smooth out the edges of the biblical Book of Esther while preserving the integrity of its form. The modifications within the translation metanarrative are, in most cases, intended to go unnoticed. The changes shouldn’t stand in the light of the original; they should remain hidden in the text. And yet, in each section of the book, the intertextual framework, the constant undoing and redoing of language, reveals itself just enough for the reader to watch Schein quietly build the axis on which the novel spins. On each revolution, it asks: What is the language required for the stories we pass on?

* *

Image: Alejandra Seeber, “Consider not understanding,” courtesy of miau miau

[ + bar ]

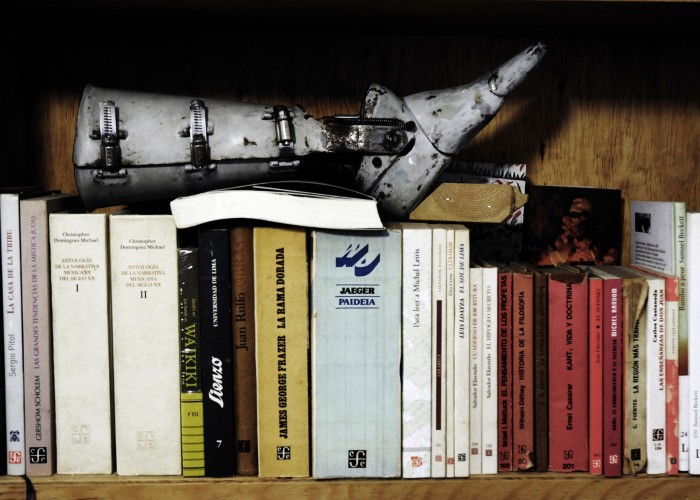

Mario Bellatin: Doubles and Outtakes

Craig Epplin

Y el eco es anterior a las voces que lo producen. —Nicanor Parra

The title of Mario Bellatin’s 2008 biography of Frida Kahlo, Las... Read More »

Tufts of Dark Hair Attached to Indeterminate Bodies

Lincoln Michel

The wind whipped salty air against Silas Woodrow’s face, but his daughter was nowhere in sight. She was always doing things like this.

Silas walked... Read More »

Dossier Bellatin

The Buenos Aires Review just turned two, and we’re celebrating with champagne and a dossier on one of our favorite writers: Mario Bellatin.

Bellatin is a luminary of contemporary Latin... Read More »

John Freeman

THE HEAT

At night as the heat’s warble strummed to a ticking silence, and the crabgrass turned blue then green then black, the branches above would relax and gently pluck my window-screen, like the dark-haired woman who, years... Read More »

sending...

sending...