The Prouf is in the Vermouf

James Warner

The first account our agency landed was a fortified wine called Clouf. Roland slammed a bottle on my desk and told me to think something up before he got back from lunch. Knowing nothing about vermouth, I started to bang out a jingle on our office piano, under the impression the product was a cleaning detergent.

When Roland returned, he poured some into a six-ounce glass. “A beautiful nose,” he said, “subtly andrognynous with intimations of hyssop.”

I tried some. Clouf pretty much tasted like cleaning detergent to me. It was wine steeped with gentian root, myrrh, bitter orange peel, hops, and various secret ingredients, then fortified with brandy. It contained more glacier wormwood—Artemisia glacialis—than other vermouths, perhaps not much of a selling point.

Like field operatives, Roland and I visited the seediest Soho pubs we could find, ordering strangers free Cloufs. Women were more willing to drink the stuff than men were. In 1970s London, wine was still something for toffs or rock stars. A publican confided to me that even cocktail drinkers were scared of vermouth, and it had been steadily declining in popularity for decades, a trend Roland and I were somehow supposed to reverse during a time of economic stagnation and high unemployment.

We agreed we’d have to highlight the product’s exoticism, and storyboarded an ad set in a bar, where a woman passes various men in suits and sits instead beside a gorilla, who is topping up two glasses. I forget if it was Roland or I who came up with the line, You’ll know him when he pours you a Clouf. The joke is that the gorilla stands out for other reasons, such as his wearing a purple wig and a space suit.

It was illegal to show people drinking in alcohol commercials, which Roland liked since it kept us focused on the moment before consumption, the point of transition to a zone of relinquished responsibility. Julia was our actress. She and the Clouf gorilla clashed their glasses together and then deftly exchanged them—a trick she learned at drama school. A bartender told me that as long as the ad was running, someone would try to imitate this trick every night, broken glass being the invariable result.

Julia had innocent eyes and spoke with a slight seafaring accent, and she struck a chord with the viewing public from the first, receiving fan mail from all over the country. She was one of those sprightly British media personalities who grow fiercer over the years, obviously destined to wind up dispensing absolutisms on topics like gardening or dog training. She and Roland dated for a while. But while the ads were popular, sales were largely unaffected—it was Julia the pubic cared about, not Clouf. When Julia actually tried some Clouf it made her throw up, although we made sure that news didn’t get around.

Like many things of genius, Clouf tended to give a first impression of being perversely wrong somehow. The bottle I gave my parents, I found still unopened in a dusty cupboard decades after they divorced.

*

We took on other accounts, but Roland was determined to retain Clouf as our signature brand. He worked on the backstory whenever he was stoned. Roland believed elaborate backstories were fundamental to a campaign—the Clouf gorilla was a spy from an ocean planet submerged in Clouf, and had come to Earth to find people willing to drink it.

A bishop accused us of sacrilege, alleging the Clouf gorilla, an extra-terrestrial who gave people wine to drink, was a travesty of Jesus. An Open University professor retorted that Christ himself was only an avatar of the Greek wine god Dionysus. Roland said this was all good publicity.

We hoped to establish Clouf as the drink of the well-connected, after a trend-setting caterer served Clouf cocktails at a key industry party. But as our storylines got stranger, with Julia picking out the gorilla in a police lineup and then in a beauty contest, our ads began to lose traction.

By the 1980s, the suits Julia so consistently spurned in our ads were cool again. Eventually our agency was bought up by a larger one. The Clouf brand itself was acquired by a French private equity firm, and we lost the account. For a while I mostly worked on shaving cream commercials.

Roland denies that he was doing a line of cocaine when he fired me.

Unemployed, I grew to resent all advertisements. Naked hard-sell tactics were back in vogue, and recruiters I showed my portfolio to found it too whimsical. I worked unsuccessfully on movie soundtracks and drank far too much Clouf—now my favorite drink. Perhaps I was subliminally persuaded by the copy from my only award-winning campaign, framed on the walls of my dingy flat, assonant slogans like don’t be so uncouf and beauty is trouf, reinforced by the image of a gorilla proposing a toast. I had a desperate need to believe there was more to a thing than how it was sold, and now that I lacked any professional connection to the brand I was free to urge people to consume it without feeling I had ulterior motives.

Few listened. A new agency reinvented the Clouf gorilla as a cartoon superhero, but the vermouth category remained moribund. In 1985 only three thousand cases of Clouf were sold in the United Kingdom, and I probably drank about half of those myself. Clouf did however enjoy a revival across the Channel.

Around 1990, I saw Julia act in a provincial production of The Merry Wives of Windsor. Her ambition had always been to be a Shakespearean actress, and it irritated her that it was for the Clouf ads she still was still most remembered. When she first came on stage as Mistress Page, a drunk had to be ejected from the theatre for yelling “Where’s the gorilla?”

When I talked to Julia in a restaurant afterwards, she told me Roland was planning to join the monastery in Clouf, where they first made the drink.

“I see what he’s up to,” I said. “He must be thinking of writing a Peter-Mayle-style aspirational lifestyle book, My Year Among the Monks or some other ingenious tie-in.” Clouf was in Savoy, part of France that was once part of Italy, the two most PR-worthy nationalities.

Julia asked the waiter for another bourbon and Coke. When I ordered a Clouf, the man looked at me blankly, until Julia and I went through the ritual of exchanging our glasses. I even made some gorilla noises, but the waiter was too young to snag the reference. What he brought me instead was a Cinzano, a vermouth with a limited range of flavors, in my opinion, saddled with one of those campaigns that wound up losing sight of the brand. Bars rarely stock reliable vermouth anyway, and for this I blamed only myself.

It was the first time in a decade I’d seen Julia when she happened to be between marriages – as long as she was unavailable I’d imagined I had a crush on her, but now I wondered how much of that had only been the glamour of our shared campaign for Clouf. She and I made out in the parking lot for a while afterwards before agreeing to call it a night.

*

It took me many letters over the course of several years to secure the abbot’s permission to shoot a documentary at Clouf, even though by the late 1990s I managed the leading website for connoisseurs of artisanal vermouth. Yes, there is such a website. At the last moment, Roland called from Normandy, where he now lived, and insisted he go with me.

Despite a prolonged midlife spiritual crisis, Roland hadn’t become a monk. He wrote marketing books now, with titles like Brandscendentalism: the Alchemy of the Product Line, and had lost all his hair, although he wore octagonal glasses that made his baldness seem almost intentional. Julia now had her own TV series, explaining how to prepare a house for viewing by prospective buyers, and could sometimes be spotted engaging in witty banter on recondite quiz shows—neither Roland nor I had been in touch with her for a while, and we avoided mentioning her.

1990s France, as we motored across it, was covered with Clouf billboards, surreal portrayals of vermouth-based life forms arising from some primordial plonk. My peeved first impression was they were the work of someone who lacked an intuitive appreciation of the niche product, but by the time we got near Savoy, I appreciated their suggestiveness.

The billboards themselves seemed to be impelling us Cloufwards.

You reach the monastery by driving through a wooded gorge. The village has a shrine to the Virgin and a school of watchmaking, where I bought a postcard to send my mother. The monastery, a complex of buildings of weathered stone, stands on a cliff overhanging the village.

Roland and I stayed in a small building in the middle of the medicinal herb garden. We watched the monks gather wild gentian plants, with their yellow flowers, and slide down scree to pluck fragrant glacier wormwood. We heard the scraping of their crampons as they ascended precipices to forage for berry-bearing shrubs. The wine was macerated with stinging nettles, wild strawberries, fennel seeds, and unripe walnuts in oak casks, then left to evaporate and mature, exposed to the elements. It was said that no monk ever knew the full recipe.

Since they no longer owned the trademark, the monks weren’t allowed to call their artisanal vermouth “Clouf”—the drink they made no longer even had a name. Roland wanted to persuade them to let him promote it for them, but the abbot just looked at him the way Julia looked at the men in suits—we were a lineup that lacked a gorilla.

That afternoon, while Roland and I sat looking down at the village, the cellar master trudged towards us in the slanting winter light, hugging an immense flagon. It turned out that he was from Stoke Newington. “I came here as part of a taster weekend,” he told us. “A cheap holiday, and you find out if the vocation is for you.”

The liquid smelled like the purplish medicines I was forced to drink as a child. The original recipe was from a medieval manuscript, and was meant to kill off intestinal worms—so it really was a sort of cleaning detergent, after all, something to purify your insides. Standing uncomfortably close to the cliff’s edge out of aging male machismo, Roland and I drank to Julia and the housing market. The taste was piercingly floral, like taking a swig of an ecosystem. There were psychotropic effects, too, which left me with sharpened senses and a faint paranoia that lingered for days. Maybe it was the Artemisia glacialis, maybe the altitude. There were also notes of bergamot and rain-dampened earth, a heart of star anise and a bottom of white amber, and drinking it seemed to wrench me into the presence of everything I needed.

* *

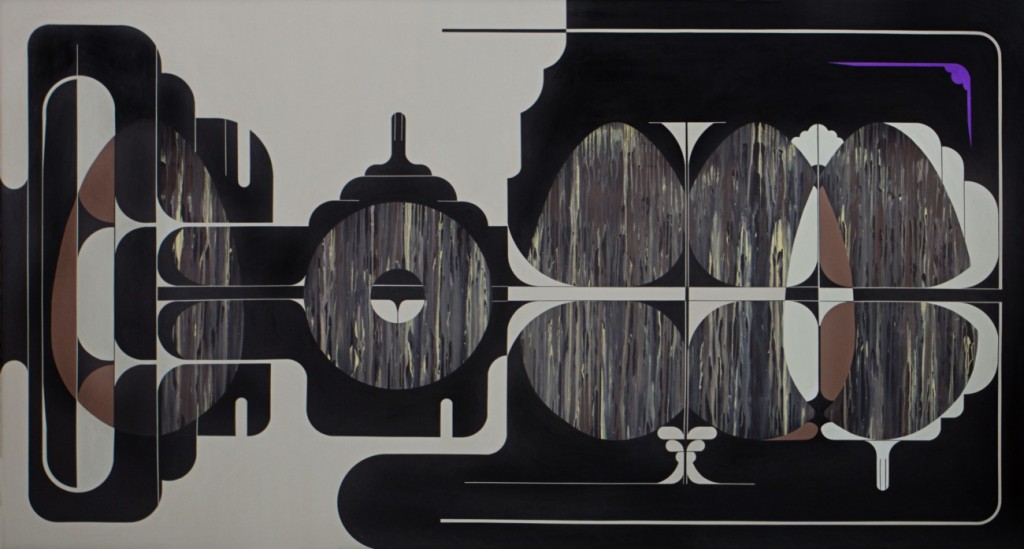

Image: Julián Prebisch, Untitled (2013), courtesy of miau miau

[ + bar ]

La Inestable [lima]

Alicia Bisso translated by Heather Cleary

I never liked poetry. My self-imposed task of learning to read it began with a strange discovery. One afternoon, a traffic jam... Read More »

from The Sofa Sages

Eitán Futuro translated by Jennifer Croft

Lara began to kiss me. I hadn’t kissed her first because I thought you couldn’t kiss them on the mouth. I touched... Read More »

Antonio Machado: Covers by Daniel Evans Pritchard

ALONG THE DUERO

A stork at the bell tower’s peak circled around its height and around the home below as the little swallows squealed. Dry winds have crossed a... Read More »

Pilgrims Book House [kathmandu]

The fire began surreptitiously, away from the bar’s carousing punters, but soon crept into the kitchen. There it licked at the piled gas cylinders, unleashing a conflagration of such... Read More »

![La Inestable [lima]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/La-Inestable-700x500.jpg)

![Pilgrims Book House [kathmandu]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/IMG_0085-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...