Among the Dead

Ernesto Hernández Busto

translated by Heather Cleary

The future is always a lie. We have too much influence over it.

— Elias Canetti

I.

It all began in September of 1991, when a friend (let’s call him I.) showed up at my place with the news that we’d be able to leave the country a few days later. I vaguely recall that we celebrated (despite the superstition about doing so in advance) and then went for a deliberately nostalgic walk around the city. I realize now that I don’t have a clear memory of that last stroll, of where we were, exactly, as though all that premeditation had generated the opposite effect: an overly illuminated screen on which we could barely make out blurred figures and places.

In another country, our departure would not have been anything special. In Cuba, it gave us the right to invent stories about our charmed relationship with Fate. I was twenty-two and had travelled twice: to a youth conference in Bulgaria, and to study math in the Soviet Union. The first trip ended up being a kind of return: the Greek girl who sat next to me on the bus to Stara Zagora reminded me of an old lady I knew, and the spectacle of Gypsies jumping barefoot over hot coals had the solemn air of a family gathering. Even today, when I walk into certain places I still catch the “scent of Bulgaria”—a mix of dairy, roses, dried fruit and air conditioning—and several parks remind me of the gardens in Boyana, residence of President Zhikov, whose daughter Ludmila, the Socialist Lady Di, entertained herself by collecting children who would talk about world peace, live together under the watchful eyes of their omnipresent instructors, and go to bed early in their little fenced-in preserve. Aside from those closely monitored nights, everything seemed perfect: sweets, flags, mansions, the freshly shaved cheeks of the reporters…

Five years later I arrived in the Soviet Union, where my affinity for math was quickly decimated: I preferred taking long train trips, dragging behind me a trunk full of books that my mother had found in the dilapidated home of a relative who had fallen on hard times. When I finally returned, the case went to the house of a friend I’ve never dared to ask about it. It was covered in real crocodile, and a group of sailors from Odessa wanted to buy it from me for what seemed a fortune at the time. There it was, unmistakable out there on the pier, surrounded by three or four brawny men. Surprised by the anachronistic object, they ran their fingers over its fastenings and reticulated skin, not believing the relic could belong to that foreign kid who seemed too young for so much luggage, too skinny for an itinerant casket like that one. I didn’t sell it, and I was right not to: armed with that monstrosity, I was able to survive the wait for trains that took days to arrive as I crossed into the Russian steppe like the hero in a comedy of errors.

It might have been better, I thought then, to have left all those books behind, to have fully dedicated myself to a future “free of the superfluous,” as someone once suggested to me in a letter. But with that suitcase, I always felt I was on the verge of a new beginning, like someone who suddenly notices that a gesture they always make, reflected in the living mirror that is their distant relatives, is more a matter of nature than nurture.

After a few months, this new panorama was blanketed in the same feeling as my previous trip: the deck of a boat, the sun-kissed houses along the banks of the Bosphorus, the golden glint of a wood floor, the soft crunch of boots on snow, only recently discovered… all this seemed like part of something inescapable: “real life,” the outside world. There was just one problem: I was only passing through. Due to some kind of temporal misalignment between that reality and my other obligations, the time I spent in those settings was always too brief: something separated it from the time to which my plans—their predetermined trajectory blurred by the sudden appearance of so many new landscapes—adhered.

When I got back from Russia, the three or four friends I saw regularly began to think of me as part of a set, as part of the set of books we would pass between us. I remember feeling the comforting aura of friendship one day as I traveled with P. to Casablanca, a little town overlooking the harbor with one train station and a solitary Christ at the top of a hill. It was one of the few trips I took in Cuba, a fact I have since come to regret.

The yellow walls of the palatial house where my friend’s father lived were covered in water stains, like a giant Rorschach test. It was a nineteenth-century villa with an open patio in the center, long, dimly lit hallways, and lustrous mahogany and wicker furniture. We had gone to pick up a few books; condemned to see his library scattered among the three or four places he used to live, my friend tried to gather his most treasured ones in an old bookshelf, a gift from an antiquarian. (A strange word comes to mind: mudada, a combination of “mute” [muda] and “move” [mudanza]. Leaving a house behind is like shedding a skin: it marks the beginning of a new season.) P. talked about his trouble holding on to books as part of an older curse: few Cubans were able to build a real library—José Lezama Lima and Alejo Carpentier were rare cases. “You have the Milanés family’s meager collection, full of Lope,” he said, “you have Varela, Saco, and Casal with his Kempis Christ; you have Count Kostia’s Parisian suitcases, the novels copied by Zacarías González del Valle, Martí’s nomadic collection, Heredia leaving Cuba without his books… Del Monte left his collection with the Aldamas, didn’t he? And the books Virgilio Piñera read and gave away.” To this day, Cuban historians have only mourned the burning of our forests (strangely enough, I think it is in this context that the word “Cuba” appears in Marx’s writings); when will we mourn our charred libraries? Those fires crushed all hope of a real literary future. We seemed condemned to carry suitcases, to talk about a few books—read with the passion of those who prefer wreckage to riches—stored in some old piece of furniture.

Later on I got a group together to do a couple of improvised philosophy courses at my place. The only condition was that everyone had to contribute their best books to the communal library. It was around then that this double “need” began to bother me: having to leave places behind, having to do things. Those books transformed the future into due time. Still, I took a tape recorder everywhere I went, convinced that the mix of confessions, digressions, and pretentious reflections I captured would be useful for something, someday. Not as a way to remember, though; in those days no one took memory seriously. The past didn’t exist—there were only plans, projects, the future towering in the distance. When I listen to those tapes now, I feel like I’m spying on someone else’s life.

The headstrong gesture of gathering books and talking about them ended, once again, with empty shelves. The people who read them are now in London, New York, Barcelona, Havana… Sometimes we talk on the phone without saying anything important. There’s some kind of unspoken rule that keeps us from mentioning those days.

“The course,” as we called it, was just a pretext for friendship, that trade in identities which so often comes down to a few biases. It’s hard to live surrounded by witnesses in a place where prudent gestures become habits that disguise indifference. Philosophy was supposed to soften those disappointments, to instill a sense of order, but our curiosity about distant lives and landscapes burned just below the surface of this interest as a desire to break through the membrane of a stifling reality and rummage around in a basement it had declared off-limits. This was not a question of strength, as we had thought at the beginning; dismembering the private meant moving like Chuang Tzu’s knife: knowing the victim’s body well enough to cut through organs without brute force.

But projects and readings meant little when a few authorizations to leave appeared and the country’s unbelievably tangled red tape was lifted, as if by magic. After treading the volatile terrain of politics and religion, “the course” was left stranded in its fledgling phase, a rite of passage eclipsed by the private study into which the adolescent emigrant retreats after his social phase.

II.

I recently discovered, in a friend’s novel, the description of a unique feeling: J., the protagonist, travels constantly while making shady business deals, until one day he realizes he has left his soul behind. His most intimate double is lost in some hostile city, so J. decides to let it catch up while he waits for letters that might give him insight into the disappearance of V., a Russian girl kidnapped from a harem in Istanbul. The novel mentions the idea of “Iamblican bilocaction,” a phenomenon discussed by Iamblicus and the Neoplatonists, a simple version of which might be the story of the man who never took an elevator because he thought his soul would not keep up with his body, and preferred that the two take the stairs together.

What I admire about José Manuel Prieto’s novel Livadia is not so much its metaphysical plot as its penchant for revealing the pockmarks of experience on its face. For J., the future is, in a Proustian sense, the anticipation of a past seen clearly, the possibility of a time recaptured in and through writing. The past, in turn, takes shape because it is accompanied by written memory, the potential metamorphosis of the real into the unreal, and vice versa: of pain into the memory of pain, of the sublime into the ridiculous sketch of the sublime, of the essential into the useless image of a life to which we add almost nothing new, making time the (only) thing that goes on.

Prieto is a careful reader of someone whose work is likely a logbook for all emigrant writers: Vladimir Nabokov. There is something very Nabokovian about this character who organizes his memories as he sets out to start a new life, an existence shaped by the idealized image of V. Here, the problem of exile is not so much a matter of struggling with a new reality, but rather one of settling accounts with a past that has become a limitless font of details. Hence his obsession with the senses, with certain unrepeatable sensations. Just like in Nabokov. The famous scene in Mary, for example, in which the protagonist tries to remember the cheap perfume his beloved wore, only to end up declaring that “memory can bring back everything but perfume, even though there is nothing the brings the past to us as intensely as a smell we associate with it.”

The strange uni-directionality of olfactory recall is also a good metaphor for the limits of memory: a certain resignation, a shrug of the shoulders in response to the arbitrary way recollections reach us is part of the adult life of the emigrant. Over time, we tend to forget the immediate; instead, images that we thought we had lost reappear a ritroso as radiant allusions along the way. Because of this, memories are interesting less for the experience of their protagonist or the moment they take place than for their details (“those wonderful details!” Nabokov dixit), those recollections of a landscape on the verge of disappearing, a backlit filigree or forgotten toy, that resonate across the life of the narrator and become the possibility of reconstructing a soul.

Together, imagination and memory allow us to connect with a lost world that offers only a succession of ghosts, of fragile archetypes that crumble when we try to take hold of them. The attempt to reconstruct the past inevitably ends in the grotesque, as Nabokov has demonstrated at different moments (most notably in Glory and Look at the Harlequins!)… In “The Return of Chorb,” one of his short stories, this bid to rewind the “typewriter ribbon of time” reveals its darker, more cynical tones.

The story is about a young emigrant writer who marries a German girl. The two decide to travel through Germany, Switzerland, and the Riviera, but she dies in the middle of the honeymoon after touching an electrical wire on a highway outside of Grasse. Wanting to be alone with his pain, Chorb does not tell his in-laws about her death. Instead, he looks back over each moment of his failed romantic getaway in reverse order, archiving every trifle he saw with his beloved. When he finally reaches the hometown of the deceased, he stops at the final chapel of his pilgrimage: the cheap hotel where they hid, laughing, from her parents on their wedding night. Unable to stand the solitude in the room, Chorb hires a prostitute—not for sex, just to fill the void beside him for the night. Meanwhile, the wife’s parents, who have had no news of their daughter in a month, hear that Chorb is there. They burst into the room and… that is where the story ends.

The protagonist of José Manuel Prieto’s novel also seems destined to an absurd end, forced to accept that life is shrouded and confused by the desire for a predetermined future, that it only draws back its veil after a few direct blows from those ineffable masters, space and time. Letting go of his “assured” future, his expected horizon, the exile becomes an emigrant.

What the English call displaced persons and the French call émigrés or depaysés are those who have lost their way, who aren’t going anywhere, anymore; they are people who have reached, in a sense, the end of the road. In German they are Ausgewanderten, a word that calls to mind a beautiful book in which W.G. Sebald, also an emigrant writer, reconstructs the biographies of four characters who at one time or another each had to abandon their homeland, abandoning themselves in the process. They are modest stories, far from any “great destiny.” And yet, recounting these lives reveals a gripping, surprising world grounded in details, in memory, and in the mysterious power these have to move us.

Of course, there is a more or less hidden homage in Sebald’s book to Nabokov, who appears in each of the stories as a minor figure: the butterfly man. These apocryphal nods are mixed in with strange images and fragments of conversations, interviews, and entries from other people’s diaries. For Sebald, as for Nabokov, emotional ambiguity is the principal feature of being uprooted: the emigrant’s feelings tend to be contradictory, tied as they often are to memory, that fickle mistress. In Sebald’s work, this malaise becomes background music: phrases stretch out and are distorted, adopt a liturgical rhythm. But only to show us something more important: by beginning this recherche in the dashed hopes of his forefathers, the narrator becomes our guide through the purgatory of memory. This is why there is no hierarchy to his memories of that hazy world—there is no ordering criterion, no imperative to burden the narration; nothing disrupts the light tread of this visitor without any real identity who enjoys walking among ghosts.

III.

Over the past twelve years, I have lived in four different countries. I have felt like a stranger in each of them, though the intensity of this strangeness might vary as it is limited by routine or takes on a nostalgic air. I have forgotten many things, moving from one place to another. I take solace in the idea that the things I have forgotten are more “personal” than those memories we cling desperately to. What is unique about each of those forgotten things, the most unsettling part, always lags behind: it is this bit of fiction in our lives that just might appear in a book—ours or someone else’s—one day.

I associate this discovery with a novel by Nabokov, in which the protagonist unwittingly goes to see a movie on which he had worked as an extra several months earlier. Seeing his own gaunt image on the screen embarrasses him and reveals the impermanence and randomness of life. He leaves the theater feeling queasy, convinced that he sold his shadow out there on the fairgrounds where floodlights point like canons at the anonymous masses. As he walks, he thinks about this shadow of his, about how it is moving from one city to another, one screen to another, and how he will never know what kind of person will see it, or for how long it will make its rounds through the world.

Reading that book was a therapeutic experience for me. Not only because, having changed countries so many times, I felt like the character who sells his shadow (an idea that recalls stories by Andersen and Count von Arnim), but also because I had finally found an explanation for the “feeling that might be described as a reverse nostalgia, that is, the burning desire to find myself in some other, unknown, place.” That sensation had a name, it could be written about, and doing so brought the character and his shadow into contact; the shapeless blotch began to imitate the movements of it owner, eventually reaching a subtle, undulating synchronicity.

Since then, I have thought of exile as the paradoxical revelation of the “essential,” as though it were only possible to get a panoramic view of life far from the predictable, known, or habitual world. By some strange effect of inertia, the most important landscapes of my past are of travels and books; it is like seeing my life reflected in a distant mirror. In exchange, this inertia offers me an imaginative space in which the “important” freely makes way for the “superfluous” governed by that flow of details by which the first seed of a sensibility is formed. Thanks to the time I have spent living outside my country, my future has come to seem less like a moment in history and more like something imbued, unlike most theories and timeworn “universal ideas,” with the tangibility by which perception achieves its subtle continuity.

When we begin to suspect that life may have a predetermined course, we string together its details and feel we have to look at the world around us differently, since each sensation necessarily bears a secret logic, or so we think. But even if our “destiny” turns out to be the pale reflection of this conjecture, we have experienced the pulse of the world. It is like the morning after a night of drinking: any flash of light is unbearable, but in this apparently dulled state we nonetheless discover an unexpected agility, an image.

When we decide to reconstruct the past, we start out with an advantage: any memory is a good place to start. Memory requires no particular lineage if you have a taste for words. A dubious repository of pleasure, the past warns us that by following time’s arrow we are betraying “something,” almost always going against what “should be” done. I am not talking about personal memories, those timeworn postcards of reminiscence, but about memory as an activity that separates us from the utilitarian side of things, or rather, that exists because it can do without that side. We are used to thinking about the life we “should lead” and the things we “should do” as “objective” realities, the opposite of more or less elaborate daydreams. But whoever sharpens their senses will find in those daydreams the secret logic of all that exists. When we dig deeper into those “real” aspirations, on the other hand, we reveal their ties to vague theories and concepts (what do success, power, and happiness mean, exactly?), if not their enslavement to the spectral world of clichés.

This is why I avoid thinking about the future, which turns the world into an abstraction and makes it hard to appreciate the shimmering dust of life. The only “maturity” with any meaning would, then, be that momentary twist when memory helps us take true measure of the present, over and against its illusory depth.

IV.

In one story from in The Emigrants, the one in which Sebald gives us the biography of a certain Ambrose Adelwarth, there is a strange allusion to “Korsakoff Syndrome,” a mental illness named after Sergey Sergeevich Korsakov (1854-1900), the Russian psychiatrist who discovered it, which involves compensating for memory loss with fantastic inventions. Those who suffer from the syndrome are unable to remember events from their recent, even immediate, past; they retain that information for only a few seconds before sinking into confabulation, into detailed and convincing memories of events that never occurred. The patients have no sense of continuity between one experience and the next—these gaps affect memories a few weeks old and those from fifteen or twenty years before they fell ill, alike—and their amnesia is never complete or consistent, since “islands” of memory can be discovered through persistent questioning. It is not any sort of radical metamorphosis, but rather a no-man’s land where imagination and delirium coexist.

Is it not possible that all emigrants need to rebuild their worlds, too? Reinvent the narrative that shapes their identity? For the emigrant, could “being himself” mean having to gather the fragments of his first-person pronoun and assemble the pieces of his inner drama, even at the expense of an ambiguous truthfulness? Is literature not a similar attempt to instill a blank canvas with reality and continuity in a fleeting world about which we can only draw connections in a frenzied kind of mythmaking? Is there something dangerous about this attempt to free ourselves, to some extent, from our servitude to immediate reality by means of its expeditious conflation with memory’s creative reconstructions?

Appearances aside, every emigrant is a futurephobe. He is not afraid of any particular future, regardless of whether that future is rosy or not for one reason or another; what he tries to avoid is perspective, anything that might organize his feelings, like those checkerboard floors you see in drawing manuals. Every so often he goes through, pretty much out of habit, the dull motions of projection, though deep down he mistrusts its domesticated, inevitable time. He understands that he has lost his “natural” time and begins to appreciate a form of imagination in which style, “that sign of transformation the writer’s thought subjects to reality” (Proust), takes on the form of a temporal inversion, the exchange of the future for the past, of the predictable for the provisional. This temporal metamorphosis in the name of style also implies a change in the way we relate to the people around us. If in a world organized around the future we are all grayish citizens of “what will be,” competitors in some pointless circular race, in a world of pure memory we are all ghosts, the living dead, characters based on ourselves.

In Atlantis, Leo Frobenius tells an unusual tale of a ghost town: “When one travels a great distance, one meets people in the market—whether in Ife, Dahomey, or the land of the Ewe—who died in their own countries and have retired there to avoid being recognized. When they see one of their compatriots, they quickly scurry away and make sure they are not seen again.” I live, along with almost everyone I know, in the skin of these zombies; withdrawn in one way or another, we wander through a lost world. We generally avoid seeing one another so as not to remind ourselves of this uncomfortable condition. (Other times, following an impulse that is the mirror image of the last, we seek these peers out so they can remind us of this feeling of estrangement.)

There is no doubt that solidarity begins to crumble when one bears the weight of something lost. It is easy to misinterpret this fact, taking it for the reflection or mimicry of behaviors found where privacy is a value. The habit of collectivization has been left behind and we are “free,” completely on our own. How much of our tendency to avoid people similar to us, those who force us to travel into the past, is grounded in fear? In recent years, I have come to believe that this fear is a key element of the emigrant’s civility, the reason we turn our memories into the gravestones of our being, of what we were and were not able to be, of what we never had and what we possessed with the joy of new initiates, of what we are not and could never be. I worry that exploring the future, for those of us who are “outside,” might become a bleak tour through these gravestones, a journey along which, at the end of the day, all we can do is dig up a few incidental bones from which to form the skeleton of a ritual figure.

* *

José Manuel Prieto’s Livadia was translated by Carol and Thomas Christensen as Nocturnal Butterflies of the Russian Empire for Grove Press in 2007.

* *

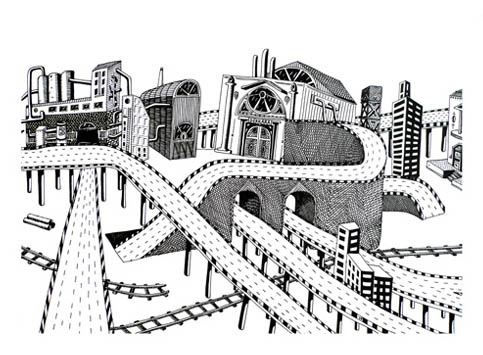

Image: “Keeping All My Ships in the Harbor” by Nadja Bournonville. Curated by Marisa Espinola for Espacio en Blanco. (More)

[ + bar ]

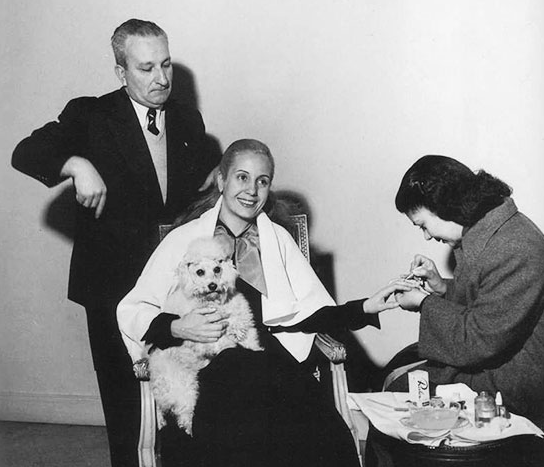

Evita Fashionista

Mariano López Seoane translated by Heather Cleary

A decade ago, the New York philosopher Jennifer Lopez gave us “Jenny from the Block,” an ode to upward mobility... Read More »

The German Lesson

Eva Marer

The German teacher lived on a street of towering trees. Their weeping boughs stroked the curb, leaving sun-dappled green tunnels you could walk through.... Read More »

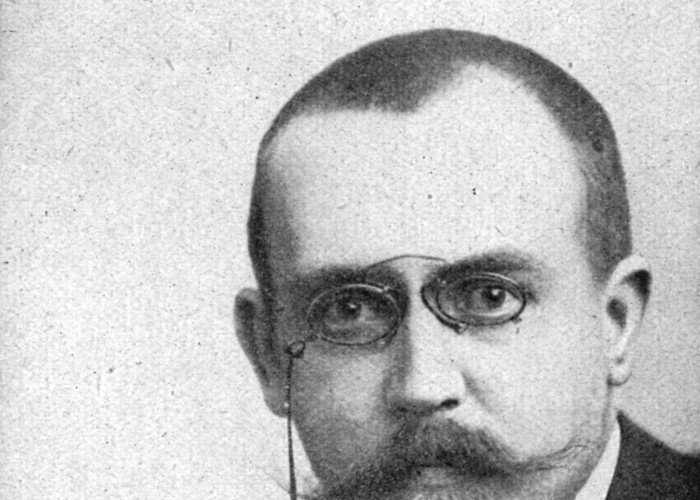

Die großen Bäume. Eine Juno-Novellette.

Paul Scheerbart

Die großen Bäume tasteten mit ihren langen Astarmen immer heftiger in der Luft herum und konnten sich gar nicht beruhigen; sie wollten durchaus... Read More »

Silence Is Meaningful

Ilan Stavans and Charles Hatfield

The following discussion of Paz and Borges as translators is part of the work-in-progress The Big Theft: Adventures of Translation in the Hispanic... Read More »

sending...

sending...