Bibliothèque nationale de France

Victoria Liendo

translated by Victoria Lampard

To Charles Coustille,

guilty of making me love France,

he who declares himself innocent of everything.

Libraries very much resemble churches: there are some that can make you feel even closer to God. There are so many libraries in Paris that it’s hard to decide which to visit on a daily basis. There’s your neighborhood library, your university library, your country’s library, the Scandinavian countries’ libraries—more modern—the Grandes Écoles, the famous ones like Saint-Geneviève, the cool ones like Beaubourg, and then there is the official, unquestioned Cathedral of French Wisdom, immense, solemn, silent: the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Against all expectations, the lofty, serious BnF is the only place in which someone as restless as myself is able to sit down and study.

Before the main branch of the library was at Richelieu, near the Opera and the stock exchange and known as “BN” (Bibliothèque Nationale). They’ve since added an “F” (as in France)—apparently a needed addition—and placed it in Tolbiac, on the east side, right up against the invisible wall that separates Paris de rigueur snobbery from the banlieue. Its new location lent it freedom of form and expansiveness. The people who designed it in the 80s thought of everything. They must have said: “let it be on the riverside,” as a metaphor for eternity; “let it boast an esplanade thousands of meters in size,” in defiance of urban modernity; and—which they somehow managed to achieve—”let it take the form of a book.” The four buildings, each 80 meters in height and in the shape of an open book, form the vertices of a rectangular esplanade 60,000 square meters in size that extends to the bank of the Seine. At the center is a wild garden into which nobody is allowed to go.

To be admitted into the most exclusive rooms on the ground floor that surrounds the garden, the first step required is purification: you leave all your worldly possessions in the cloakroom, keeping only the bare essentials in a plastic briefcase—transparent, like the study rooms, the garden, and the cafe, the walls of which are made entirely of glass. Before passing through the final turnstile, you must open four enormous metal doors and go down two flights of an endless set of escalators. At times I feel as if I am following the descent of Orpheus, other times I find the Get Smart theme tune stuck in my head as I navigate the secretive doorways. Once inside, in your own area and with your materials brought from home, procrastination involves the bleak prospect of physical exertion which, allied with the guilt brought about by leisure time, quashes any desire to attempt an escape from your blank page. The bathroom is twenty minutes worth of carpet and four Maxwell Smart doors away. The café, the same again. You thus resign yourself to spending several hours under the blanket of silence.

For every room, a letter. For every letter, a mythological character. It is said that in V there are girls as beautiful as nymphs. The nerds in R will bring about good work. Their concentration is contagious, but you will fare poorly if mired in existential angst, for they are scientists, and know that we do nothing but invent things with our words. I prefer U. There is sunlight, there are friendly faces, and all the books we need are at our fingertips, although some have yet to arrive. You get all kinds of hubris in U. Dissertators flaunting piles of books they will never read. Computers abandoned for hours, yet monopolizing the only available internet cable. Latin-American work-mates who breathe heavily as they write, as if aroused by some unspecified excitement. We all need a bit of privacy when studying. To this end, many U’s secretly emigrate to S at the far end, or they cross the border—the impenetrable garden—along its perimeter, and after a long stretch of red carpet arrive at the other side, at P, at O, at M, where the frustrated or pretentious psychoanalysts gather.

Sometimes, while traversing the red carpet that connects the study rooms, the Café du Temps, and the bathrooms, I see rabbits on the other side of the glass; mother ducks with their trail of baby ducklings, flocks of birds unaware that they are no longer in the wild, but the most surprising creatures are seated on this side, in the study rooms, on the staircases in the hallways or in the café, where for five o’clock tea the intellectual fauna emerge for a sort of wild leporine display of their own. My favorites of these are the French lit folk, whose finest asset—besides their attire, taken straight from the films of Truffaut—is in responding in the emphatic negative to any question asked of them. Talking among themselves, they complain—in sly competition—about the page count of some dissertation or another, as if they were New York finance men comparing bank balances without the slightest inkling that they may well be yuppies too, in their own way. We faithful dissertators of the BnF are united by the shame of the plastic cases we carry that really look like the plastic trays you see in school cafeterias; by institutional rivalries; the certainty of an uncertain income; and academic desperation. We are divided, meanwhile, by a delicate and unspoken caste system built on the basis of literary tastes; the awareness of aesthetics or the intentional lack thereof, as evidenced in dress; by name-dropping, and by what I call “name-manner.”

Saying “béhène” (BN) is not the same as saying “béhèneffe” (BnF). The BNers—as was explained to me by a BnFian friend when I asked about the difference—are nostalgic old professors who were around during the times of the Richelieu location and who now flaunt antiquity like a luxury accessory or who put it on when they want a retro look. For our generation—said my friend, and I saw that it was true—the default was to be a BnFian, given that the acronym “BN” has been stricken from all official documents by now, the library’s employees all use the F, and the website is www.bnf.fr (it was here that my friend noted his allegiance to this group). But there is a third category: the under-30 BNers. Serious snobs or just imitators of their elders, these people affect an impossible agedness for the vile purpose of seeming to have academic credentials. “C’est très malin,” said my friend, it’s such a cheap way of basking in apparent authenticity for anyone who utters these initials in an academic conversation. Even among long-time BnF veterans, the difference helps to distinguish between the initiated—whose career paths will no doubt be admirable—and the profane—said my friend, gazing downwards—who are really shooting themselves in the foot when they say “BnF.”

But there is another type of BnFians, for whom my friend predicted a bright future (he belonged to this type). Though not belonging to any oral culture, these men of the written word insist on typing “BnF” and never “BNF,” as the vulgar do, or, even worse, “BNf,” as the posers do, hoping for a likeness to the NRf (Nouvelle Revue française). This overcorrectness can be compared with the use of “École des Hautes Études” (mark of the feisty connoisseur) for “EHESS” (mainstream), or, too, the use of “Ulm” (the name of the street) for “ENS” (École Normale Superièure), intended to make it quite clear that they, having graduated from the university’s Latin Quarter branch, are not among the icky offspring of Lyon, Fontenay, or who-knows-where-else. Even more serious is the distinction made by true perfectionists between the use of “à la Sorbonne” and “en Sorbonne” (it’s one thing to go to school there and another entirely to attend a conference held in the historic building). Here my friend refused to name names. “C’est trop grave,” he said solemnly. In sum, he said, the BNers are either ancient morons or super-duper ambitious; the BnFians are either very innocent and undereducated, or spineless and ignoble.

Entering the BnF is a real commitment; it is to engage in ritual, and to suspend the anxieties of the everyday—quite unlike studying in the swaggering Pompidou library, where pop, color, food, TV, clochards, hipsters and low muttering stand as trademarks of freedom and knowledge. In Beaubourg you feel as if you were in Brooklyn, but in the BnF you are, quite definitely, in France. Differences aside, at the end of the day we all find ourselves in the same purgatory, fighting to reach Paradise. Every dissertator experiences their own crisis of faith. Once, a despairing Italian came into the cafe crying: “I have no dissertation, my dissertation does not exist,” to which a French workmate answered, exhaling the smoke from his cigarette, “aucune thèse n’existe.”

* *

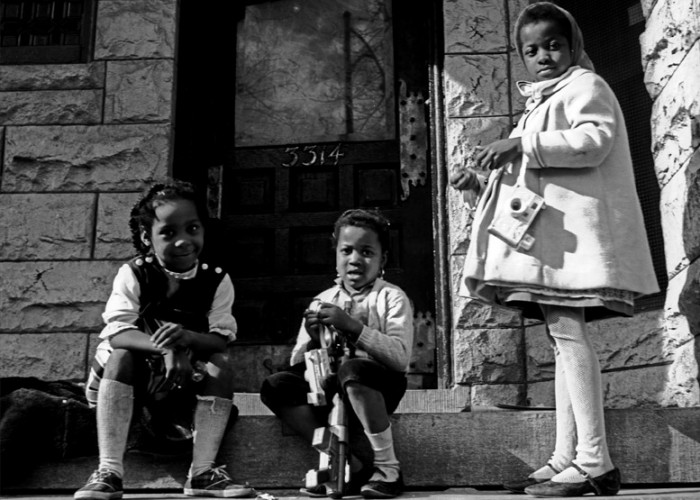

Images: Victoria Liendo

[ + bar ]

Love

Zhang Ailing translated by Qiaomei Tang

It is true.

There was a village. There was a girl from a well-to-do family. She was a beauty. Matchmakers came, but... Read More »

O caderno de Natanael

Veronica Stigger

Opalka entrou na pequena sala da casa de seu filho Natanael e caminhou até a janela, embaixo da qual havia uma mesa quadrada de... Read More »

“I’m still falling” — Jeffrey Goldstein on Vivian Maier

Interview by Eliana Vagalau

Jeffrey Goldstein’s life took a very dramatic turn when he came into the possession of a large part of Vivian Maier’s artistic legacy. Now... Read More »

Arrebato [madrid]

Juan Soto Ivars

I used to live in Madrid, but now I only go when I’m able, and feel like it. When I get there I perform certain... Read More »

![Arrebato [madrid]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/castigado-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...