“I’m still falling” — Jeffrey Goldstein on Vivian Maier

Interview by Eliana Vagalau

Jeffrey Goldstein’s life took a very dramatic turn when he came into the possession of a large part of Vivian Maier’s artistic legacy. Now the Director of Vivian Maier Prints Inc., Jeffrey is a Chicago-based artist, carpenter, and collector who has dedicated the last couple of years to promoting Vivian Maier’s photography around the world. He has also been able to use the project as a springboard for vibrant discussions about art and new collaborations.

*

Eliana Vagalau: An artist yourself, as well as a collector, you are, today, the name behind Vivian Maier Prints Inc., a project which you run passionately and which will serve as our starting point. Tell us in brief how it was that you first came into contact with Vivian’s work.

Jeffrey Goldstein: I’ve been collecting since college. As an artist, I think it’s important to collect other people’s work, as an influence, but also as sensibilities’ checks and boundaries. It’s always nice to find works that reinforce what you’re doing; I think that’s why a lot of artists’ collections look so much like what they do. I’m also a rabid flea-market-goer and antique-buyer, and spontaneously a garage-sale goer—I’m curious, so I’m always looking for things, and there are a lot of wonderful things out there.

The long and short of it is that I knew some people from a flea market I go to who were at the original auction where the Vivian Maier material came—there was no Vivian Maier at that point, she didn’t even exist. One of the original buyers owed me a substantial amount of money, and so what they did, was they made good with Vivian Maier original vintage photos, which at that time were just starting to have some value. Now that I think about it, I don’t think that a single photo had yet been sold. And so we based the original value on what one gallery owner thought that they could sell them for at a show in New York. And so that was maybe the first established price of a Vivian Maier vintage work, which at that time was $250 per print. So that’s how I started segueing into this, and I thought that would pretty much be it. Normally, ten out of ten art projects fail, and this is just different from anything else, vastly different.

EV: When did you first sense that that was the case?

JG: I was guarded for the first couple of years with this, even after we’d had a few successful shows. The concern I had was that it was just the human interest story that was propelling it forward and that the work itself was going to get overlooked. Because, ultimately, the art has to stand on its own, without the backstory. You know, when you walk into a museum, and the piece is on the wall, there isn’t somebody standing next to it telling you the history or the story of the artist. I always thought the work had tremendous qualities to it. I have this inner bell that goes off when I see pieces of work that just strike me as being masterful. And these had that quality.

As far as a defining moment, I think it was when other media started showing interest in the work, not just photographers, but other artists—musicians, authors, film makers…. Somehow, the sensibilities in the photography breached through the world of photography further into the larger world of art, and usually those different pools of art interests don’t mix: painters stay with painters, photographers with photographers.

EV: As a matter of fact, I know that you had been collecting for a long time, long before this—were you collecting photographs specifically?

JG: That’s a good question, because I’ve gone through this incredible learning curve. What I’d collected in the past were mainly prints, but not photography, lithography and etching, you know, the idea of multiples, so with those sensibilities I could segue, in a physical sense, towards the multiples of photography. But I did have to go through this curve – besides the project unfolding, reading about the history of photography, photographers, becoming more aware of perhaps more obscure photographers and photography movements. In some ways, it’s far more condensed a timeframe than, say, for painting, which goes back to prehistoric times, and through many more periods and changes, whereas photography has a well defined start date in the 1830s. And in some cases, it really shifts when the digital age starts, so that timeframe is relatively short. So, learning about that, learning about the dark room process, learning about the sensibilities of photographers, which are different from painters’.

I had a carpentry and cabinetry business that I ran for 32 years previously to this, and I worked for some of the best-known Chicago based artists, who were also friends, and gallery owners, and collectors, so there’s this triad—and I imagine it’s a very dysfunctional triad, a lot of distrust—and each element of this three-pronged wheel needs the other in order to survive and move forward. So, I’ve navigated between those three entities—both in art and cabinetry-making—and have great empathy for all three, because they each have an upside and a downside that you have to deal with. And I enjoy working with gallery owners, because I constantly hear stories about how hard they have to work, how many times they do these things that don’t work—the financial loss, the time loss, the difficulty of dealing with quirky artists. So, knowing all that, it makes things easier for me to navigate through these people.

EV: And also, I imagine, to navigate the different roles that you are now taking on as well…

JG: Yes, and they’re pretty extreme. Everything from the physicality of packing and shipping, which I enjoy, because I suppose it’s reminiscent of cabinetry work. One thing I’m sometimes frustrated with is that there’s not a tangible product at the end of my day, at the end of my week, or at the end of the year, like there is with cabinetry-making or painting. I do everything from cutting the material for packing—I have a laser machine to make the stamps that we use for packaging—setting up the frame orders, putting the frames together, and then shipping. Two days ago, we had packages at FedEx that were going to Minneapolis, Cleveland, Shanghai, and Toronto, and there are all sorts of paperwork that go with that, different packaging systems… And I have to do contracts with gallery owners, sometimes international. And then international travel, which I love to do. So, my wardrobe is very interesting, because it’s morphed from construction, over time, to suits, and coats, and pants. I just got a pair of Italian dress shoes! I have to look the part, I represent the project.

There isn’t anyone in the project who is any more or any less than another, it’s really more of a group effort, so actually the title on my card is changing. I’m officially president, because I had to incorporate a company, and I feel that that’s really ostentatious and presumptuous, and so I’m changing it to director, because it’s not such an overpowering-sounding role, and I like to maintain a great deal of equity between the people who are all part of this. Although I do have Italian shoes, and they don’t!

EV: Italian shoes notwithstanding, one thing I noticed when I had the chance to spend a little time here was that you make a concerted effort to make this project a people’s project. You make an effort to impart responsibility, delegate, and, in a sense, use it as a ramp. Where does this impulse come from?

JG: I almost want to say from not wanting to accept full responsibility, in a certain sense… But I think in this kind of a project, you’re far more fortified as a team and, given the expanse of this, I know my limitations, and the idea is to bring in professionals. This is a multifaceted project, and you bring in people who have been working with a certain facet for a lifetime. And I’m really happy to say this, and appreciate the question, because I’m a very collaborative person by nature, and I don’t feel that anybody really owns a piece of artwork, or owns a collection. You’re the caretaker, the provider for it, the idea is that each generation takes over. It’s like archaeology, there’s a job of preservation, and, if done right, it allows the next owner, or generation to glean new information from it. The idea is that of a collective coming together. The new person coming in is in her twenties, Anne is in her thirties, I’m in my fifties, Sandy, one of the printers, is in her fifties, Ron is in his seventies, we have someone here who is in her sixties, the only age-range we were missing were the forties. I think this is important because times are changing so quickly that each of these ten years is almost a generation. And they say Vivian Maier is the people’s photographer, across the board, and I think that having people from these different age-groups is instrumental in assisting that.

EV: And probably also in understanding the different stages of her work…

JG: Surely, there are different insights. When you read a photograph, you’re saying something about your personal experience, you’re projecting, and so certain photographs may be far more appealing to certain age groups.

EV: It’s interesting to hear you speak about the idea of ownership, or, rather, non-ownership of a work of art. And I am wondering if that has anything to do with the fact that Vivian Maier really did not take ownership of her work in a sense, never planned on displaying or showing her work. Did that have an influence in the way you are presenting this project?

JG: No, there is a certain sense of non-possessiveness that she has, and maybe there’s just a parallel. I’ve gone through this process once before when my close friend Ed Pashke, a famed painter, died, and I had to dismantle his studio. And it’s like dismantling a friend, a person, and archiving his work, which is, in a sense, also a dismantling process, so that experience has really helped me with this. Morally, the question that has been asked is whether this is the right thing to do, would she have wanted it. And I think that at this point it is totally irrelevant. An artist has the option, and they should exercise the option, of editing throughout their life. Her body of work is completely unedited. They also need to make arrangements towards the end of their life, or at any point of their life. If I die next week, what happens to my work? And if it’s important to them, they need to make arrangements. Most artists don’t, and they end up dumping it on their kids. There’s just no proper way of handling it. She made no arrangements; it was obviously very important to her because she kept it throughout her lifetime. Whether she had ultimate goals with it or not, I don’t know, but it was very important to her. So my job is to maintain that level of importance.

EV: Her work having been excavated so recently, what, from your perspective, has made of it such an explosive phenomenon?

JG: I think there are a handful of reasons. Part of it is that she was such a miraculously good photographer. She was able to see an image a moment before it happened. There’s a timing element. Over and over, she captures the pinnacle or epitome of what might just be a small drama in the street, but she captures it exactly at the right moment, which means that she would have to click the shutter a nanosecond before it happens, which means that she was able to see that two nanoseconds before. So she had this uncanny ability to compose, and shoot, and hit the mark with one shot. She rarely, in fact, never bracketed, it was one shot and then on to the next thing. So in part it’s the quality of her work, but also the change in technology. Photography is so explosive on its own now; anyone can take a hundred photographs now and discard ninety-nine of them at no expense. So I think it’s also the recognition of how incredibly unique and rare it is for someone to go through the process of film, and dark room, and be able to capture shots of that quality. And the imagery is very compelling, and very informative. She hits into, in a certain sense, the world of fashion, architectural photography, the gamut of what she shot—people, animals, gardens, flowers. She shot things that all of us have seen, on a day to day basis, but we never have considered shooting, and most of us could not shoot those things as beautifully as she has. A couple of examples are tomatoes on a windowsill, or a pair of dish gloves sitting by a sink. And to make those into a metaphoric statement… Last but not least, Vivian Maier gives many of “us” a sense of hope. A sense of hope in that if we don’t achieve a certain degree of recognition in our lifetime that perhaps someday, somehow, somewhere, someone would recognize through what we have made and left behind, the indications that a noble and worthy life was led.

EV: I remember looking at one of the photographs with you representing a hand clutching a dollar bill behind a person’s back, and you saying that that would be more appealing to an American audience. And yet you have had so much international travel of late—Shanghai, Poland. Have you noticed a lot of cultural difference in terms of the reception of the work, or have you developed an eye for that?

JG: I think that there’s a classical, universal quality to the work that is appealing, whether you’re in Shanghai or in ParisThe hardest thing for me with this entire project, and there have been a number of difficulties, from financial, to sleep deprivation, to getting things to places on time, was public speaking. It’s the most common fear, and I had it. But one of the most important things I’ve learned in the arts, from Ed Pashke, was that if you want something, you just have to jump off the cliff. So the acquisition of this was totally jumping off the cliff; the public speaking, totally jumping off the cliff. And, in many ways, I’m still falling, not knowing where I’m headed, but I can’t think of a place I’d rather be. And, concerning the public speaking specifically, the response of the audience is very inviting, because it’s constantly been good. I don’t think we’ve had to defend points, but people ask us genuine questions, so it’s an opportunity to describe what we’re doing, and once we do, I think people have an even greater appreciation of what’s taking place. We’re always nervous before the talks, but we realize that these are fellow human beings who have a love of art and who are curious, just like we are.

EV: As you are travelling and opening all these conversations about art, about photography, about street art, and seemingly using this project as a springboard for others, where do you see it all going? In other words, is there a secret agenda, and are you trying to take over the world?

JG: If I told you, would it be a secret? This is a really great question, and I haven’t quite yet been able to verbalize an answer yet. Somehow this project hits the chord of what is supposed to be profound about art. It’s a level of communication and interconnectedness. A level of non-verbal communication that takes place in the world of art that creates fraternity, this brotherhood, beyond gender, race, creed, religion. There is a divine feeling to this- and I’m not a religious person- of an interconnection of how close we all really are. So the one thing I may be doing right about this is releasing it, and giving it a life of its own. People are connecting with it in different ways; it’s like a snowball going downhill. People are getting on board the snowball, adding something to it, it’s getting bigger, bringing in different media, and then somehow we’re all interconnected, in this case through the work of Vivian Maier. I think it’s a profound role that art plays, adding order and beauty to our lives on many levels, and that is maybe is easy to overlook in today’s digital age. But again, I haven’t quite yet found the right words for it- profound or cosmic- they sound a bit over the top, but there is something universal about this that strikes a human chord. I’ve never seen so many people so interconnected around something, it’s magnetic.

EV: I was struck by something in your biography, which mentioned that you see collecting as an extension of your artistic practice. Seeing your experience with this project, is there really much of a boundary between the two?

JG: Not for me. Not any longer. This project has impacted me so greatly, I no longer have an idea where things start and stop. My private life and my work life, as an artist or a collector… honestly, I don’t even know what my role is. I don’t know what I do, and I don’t know what title to give myself. It’s like the tide has come in.

EV: Then would you maybe like to end with an attempt at describing to us who you are?

JG: Yes, I can tell you who I am. I am the luckiest person I know, and I felt that way for years and years, way before this Vivian Maier project. Maybe because I had a rather unusual life style and unusual events have happened to me. Being born in Florida, moving to Las Vegas in the 60s, my mother died when I was young, we moved here to Chicago two days after the worst snowstorm in the history of Chicago… Becoming friends with my heroes, who were artists and whom I’d studied in college, which is why I’d come to Chicago. I’d moved here because of the artists, and became friends with them. And I had something to offer by way of cabinetry that was different from what they were offering. I’d worked in steel plants, I’d worked for a living, I’d worked with my hands, I’d traveled fairly extensively, so I had something different to bring to this art world that was otherwise somewhat insular. I’m fourth generation carpenter, and the first one who had the luxury to be able to go to college, to study art, which is what I have the most passion for, to be able to make a living, to collect art. What more could a person really ask for? And then this project comes along and brings it all together, and there’s also something completely new that comes out of that. If I were struck by a bolt of lightning right now, I’d be fine with it.

* *

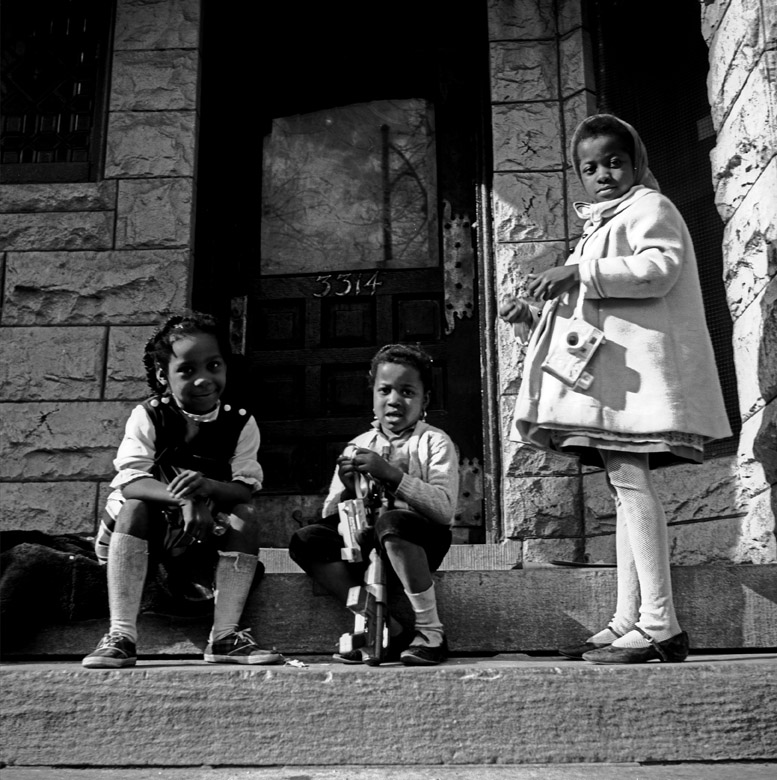

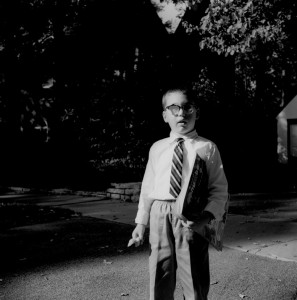

Images by Vivian Maier courtesy of the Jeffrey Goldstein Collection

[ + bar ]

Cidade Livre (fragmento)

João Almino

Minha insônia de hoje é o prolongamento daquelas horas quando, na escuridão da noite, eu ouvia barulhos de bêbados pela rua, os latidos de meu cachorro... Read More »

Prairie Lights [iowa city]

Hugh Ferrer

For as little as $140, anyone now can now buy his or her own little bookstore—for that is essentially what an e-book reader is: a combination... Read More »

La Inestable [lima]

Alicia Bisso translated by Heather Cleary

I never liked poetry. My self-imposed task of learning to read it began with a strange discovery. One afternoon, a traffic jam... Read More »

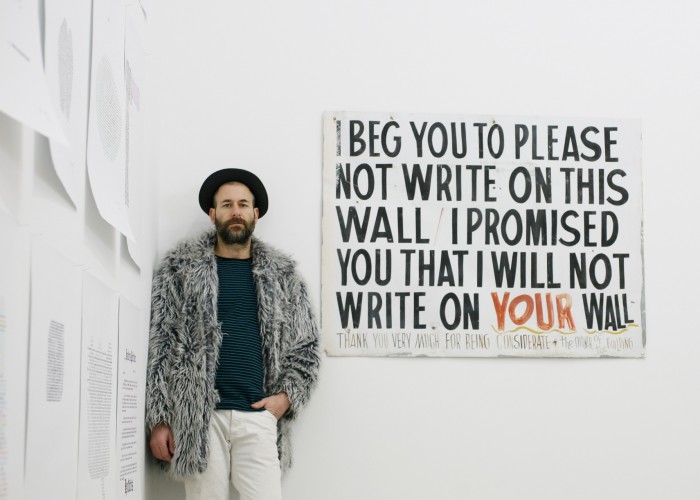

After Kenneth Goldsmith: an interview

Michael Romano and Kenneth Goldsmith

I.

I have a bunch of questions but they’re still pretty disorganized in my mind.

So let’s just shoot.... Read More »

![Prairie Lights [iowa city]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/jlc-Prairie-Lights-Facebook-Photo-700x500.jpg)

![La Inestable [lima]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/La-Inestable-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...