Ukrainian Tales of Buenos Aires

Stanley Bill

In the late 1920s somebody shot and killed a Ukrainian railway worker named Mykhaylo Marusiak on a street in Buenos Aires. The date is unknown. The circumstances are unclear. The man who pulled the trigger was a fellow Ukrainian railway man from the same southern corner of what was then Poland. The incident probably took place somewhere in an immigrant quarter of the city, which in those days teemed with fresh European arrivals hoping to ride what would later prove to be the last wave of Argentine prosperity before the Great Depression and the subsequent decades of decline. Long before Ukraine came into existence as an independent state, Marusiak was one of thousands of ethnic Ukrainians from the poorest regions of interwar Poland to sail for Argentina in search of economic opportunity. A bullet in Buenos Aires put an end to his hopes and plans.

Almost a century later – after the battering gales of total war, forced population exchanges and Soviet totalitarianism – I listen to this story in a cramped rehearsal room in the west of Ukraine over a beer with Andriy Yurkevych, the great-grandson of Mykhaylo Marusiak. Andriy works as an actor and director at an alternative theater company in the small town of Drohobych, near the present-day Polish border. His town has seen its own mini-uprising in recent months, forcing its corrupt post-communist mayor out of office in the wake of the revolution in Kyiv. As in the capital, positive change in the provinces has been heavy with the threat of violence. Young people like Andriy are anxious about the looming possibility of armed conflict with Russia or even of a fratricidal war in the eastern part of the country. In the meantime, the grind of daily economic life continues to worsen. Emigration to South America is not an option today.

Mykhaylo Marusiak made his journey across the Atlantic in the late 1920s when unemployment was high in Poland, especially in the eastern regions. Argentina’s economy was still comparatively robust. There was work for men with strong backs and railway experience. Marusiak had no intention of emigrating for good. He was no pauper on his own patch of native land. The locals called him “the American,” since he had worked a stint in Argentina once before. With pesos in his pocket, he had returned to purchase a forest near his village in the Bieszczady Mountains, which must have made him something of a minor potentate in those parts. Then he sailed back to South America to save more money for an unknown future enterprise that perished with him on that Buenos Aires street. He left a wife and two children back in Poland. The family lost the forest after the war when they were expelled from Poland to the Soviet Union along with hundreds of thousands of other Ukrainians along the new eastern border. Today, the forest may no longer even exist.

The senseless death of Mykhaylo Marusiak was not murder, but rather a tragic accident. Every Sunday, members of the Ukrainian community in the Argentine capital would congregate on the street to buy, sell and barter goods among themselves. On one of these informal market occasions, Marusiak came to exchange his wristwatch for a revolver. As he handed the precious timepiece over to the other man and reached for his new prize, the gun went off and shot him. He died on the spot. Witnesses established the unintentional nature of the incident beyond all reasonable doubt. The police did not trouble themselves with an investigation. Perhaps they simply never received any report of a dead Ukrainian immigrant from Poland. Someone made arrangements for the body to be cremated.

The other man’s response to this absurd and terrible event was both astonishing and comprehensible. He decided to make the long journey back to Poland to face the family of Mykhaylo Marusiak – to explain what had happened in person. He boarded a ship in Buenos Aires. He sailed out into the muddy waters of the Rio de la Plata, leaving the high-rise buildings and the cremated remains of his dead countryman behind him to fall away beneath the curve of the earth. Presumably he had neither the opportunity nor the right to take the ashes with him. He had no formal association with the family. Only the accidental shooting had brought them together.

The ship carried him out into the ocean, far from the great land masses and the populous cities on their edges. The voyage took three weeks. Perhaps he paced the decks day and night. Perhaps he scarcely left his bunk. Perhaps he drank and played cards with other travelers. When he reached Poland, probably through the newly constructed port of Gdynia, he set off by land to cross the length of the country, from the Baltic down to the Bieszczady Mountains, where he arranged a meeting with Kateryna, the young wife of Mykhaylo Marusiak. First, he apologized for killing her husband. Then, he asked for her hand in marriage.

She refused.

Andriy Yurkevych tells me that his great-grandmother was a beautiful woman with no shortage of suitors. She never remarried. The family survived on a pension fund from Argentina that Mykhaylo Marusiak had established through his work on the railway. In 1946, Kateryna and her two children had to leave their village and the forest that her husband had purchased with his Argentine savings. Nervous Polish security forces packed them into a transport and shunted them across the new border into a new life in the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic. They settled in the town of Drohobych, a mere fifty miles from their home village, but separated by a line on a map that deportees in Soviet Ukraine were not permitted to cross. So Andriy Yurkevych grew up in Drohobych with the family tales of his great-grandfather’s ashes resting in a Buenos Aires cemetery.

The present-day connections between Argentina and Ukraine are tenuous at best. Both countries find themselves high on the list of states most likely to default on their sovereign debt. Otherwise, they belong to separate worlds, plunged in their own very different morasses of economic, political and social turmoil on opposite sides of the globe. Argentina faces strikes and unending inflation. Ukraine is in danger of falling apart under the dual pressure of external interference and internal division. Yet, as the crises and calamities of political humanity roll on and on, I find myself thinking about the fine strands of individual lives that pass between disparate countries and continents, forming the sometimes unexpected ties that stitch the world together over oceans of space and time.

I think of Mykhaylo Marusiak and the ghostly threads of destiny that run through the swells of the Atlantic from a small town in the west of Ukraine to the Argentine capital. I think of older notions of honor and responsibility coexisting uncomfortably with the modern networks of global capital. I think of the fatal bond that ties a young theater director in post-Soviet Drohobych to the railways of postcolonial South America. I think of a forest of pesos in Poland. I think of shifting borders, while the borders have shifted once again. I think of immigrants all over the world, borne far from their families and forests by the tides of economic hardship and opportunity. Most of all, I think of a nameless Ukrainian man traveling alone by ship back to Argentina, somewhere in the middle of the ocean, with a failed marriage proposal and the death of a countryman weighing on his conscience.

* *

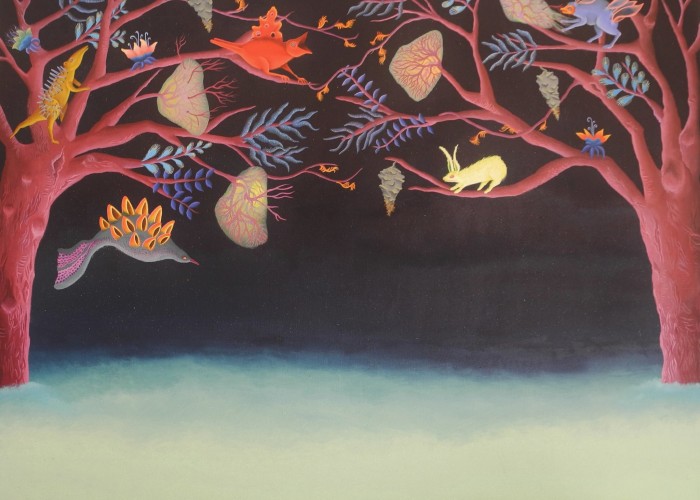

Image: Stanley Bill

[ + bar ]

Trees at Night

Ramiro Sanchiz Translated by Audrey Hall

On the outskirts of Punta de Piedra, there is a bar a good distance beyond the last line of houses. From the untidy... Read More »

O caderno de Natanael

Veronica Stigger

Opalka entrou na pequena sala da casa de seu filho Natanael e caminhou até a janela, embaixo da qual havia uma mesa quadrada de... Read More »

The World Wide Widener

Patricia Marechal

The story of Widener Library starts with a tragedy. Widener is not only a place of study and one of the largest reservoirs of books and... Read More »

Yolanda Castaño

“Aquí o que nos falla é que non nos sabemos vender”, queixábase seguido o teu patio de veciños; pero cando chegou para o quinto dereita aquel tipo que si o sabía... Read More »

sending...

sending...