The Teachings of Tour13

Caitlin Bruce

Tour Treize is a former HLM (Habitation à Loyer Modéré or rent controlled housing) building that has been turned into a 360-degree art space, covered floor to ceiling with graffiti and street art installations. Over a hundred artists from more than sixteen countries were invited to create site-specific works that transformed the housing development from living space to art space. A six month secret collaboration between Gallery Itinerrance director, Mehdi Ben Cheikh, the Mairie of the 13th, and the owner of the building ICF Habitat la Sabilière, the project explores, among other things, the relationship between ephemerality and urban space.

The nine-story building, one of many modernist style structures that went up during the second major phase of urban renewal in France in the 1960s and 1970s (following the 19th century urban renewal practices initiated by Baron Von Hausmann) was, initially, a response to the need for housing for populations at the economic margins. Largely constructed on the periphery of Paris proper, HLM housing has since become a visual trope for instability, threat, segregation, and the failure to achieve social stability through modernist design.Tour Treize emerges, then, from a complex milieu where state-supported housing is aligned with state-sponsored art making. In France, unlike the United States, the government heavily supports the arts, enabling a large degree of experimentation and genre-transforming developments since practitioners are not (as) beholden to a profit model.

Ben Cheikh imagined the project as a way to stage the ephemerality that characterizes street art as a form and to create an aesthetic experience that was free, open to the public, and impossible to sell. Accordingly, the building was open for only one month, from October 1 to October 31, 2013. The Tour13 website, created in collaboration with website designer and filmmaker Lallier, offered a virtual tour of the building, replete with interviews from participating artists. The website would only exist for ten days after the closure of the building, and could only be “saved” by viewers clicking on the website content, pixel by pixel. Any content not saved would disappear after November 10th. In suggesting an alternative mode of urban citizenship, less acquisitive and more inquisitive. the project sensitizes us to the plurality of worlds constantly in the making in plain sight and beneath the radar of more official urban production.

Visiting Tour Treize: Patience and Urgency

To visit Tour Treize, situated a quarter kilometer west of Bibliotheque François Mitterand, one had to brave a line of people that wound around a full city block. Because the building was slated for destruction and not as sound as it had been in its prime, there was a 49-person limit, meaning that the guards had to institute a one-person-out and one-person-in policy. Pragmatically, this meant that if one secured a place in the queue 50 meters from the entrance, a four-hour minimum wait was in order.

The wait on the queue tested patience, but also was a singular experience of camaraderie and excitement. I myself tried three times to enter the building, first waiting for two hours, then four, and then seven and a half. The third day I had learned what to do: arriving at the site three hours before full light, I had packed three meals, an extra scarf and hat, and a dense book to read. There was no movement during the several hours before doors opened, so people took a seat on the pavement, or on little foldable stools, and closed their eyes, listening to music, reading, or quietly eating breakfast. Some expansion occurred when the friends of early risers arrived, but there seemed to be an understanding that the place of those stalwart folks who had committed their wee hours to the line should be respected.

Above all else, however, was the exhilaration of watching visitors exit the building. Beaming, laughing, stupefied, repeated encouragements were delivered to those still in line. “It’s just…wow!” “Incredible,” and more direct support, “Bon courage!” After seven hours surrounded by the same four to six people, a sense of communitas developed, conspiratorial smiles and nods were shared as the line advanced, and later on, glances of recognition were exchanged inside the building itself.

I linger on the affective experience of waiting because it pointed up the temporariness, and singularity, of the exhibit: if one didn’t see it now, it would be gone. This experience can be understood as a form of what Greg Siegworth and Melissa Gregg describe as “sensorial pedagogy” – teaching publics to be more attuned to practices through an emphasis on experiences of the senses. In the case of Tour 13, the experience of waiting instilled in the visitor an acute awareness of small shifts in the surroundings as one advances forward, inch by inch, hour by hour. Once inside, a variety of three-dimensional reappropriations of domestic space enabled the viewer to see crumbling walls, gutted bathrooms, and empty kitchens as potential scenes for creativity. The fleeting nature of the exhibit was differently articulated in the works themselves, in which a central theme was the relationship between temporariness and creation and destruction, as matters of both content and form.

Experiencing Tour13: Internationalism, Fragility, and Memory

The building was organized loosely around national and regional affiliations. Each floor contained the work of artists from two to three bordering nations, and floors were graphically connected by graffiti that ran up and down the stairwells and hallways. Because of the limited body count allowed in the building, the viewing experience was less crowded than one might have expected. Such intimacy also conveyed the experience of being an explorer (urban exploring, or urbex is a popular past time in Europe for street art aficionados).

Entering the first floor, one is confronted with a map of Syria on the floor, made out of pita bread, above which hover a cluster of bombs in the form navy-green paint cans with little wings attached.

The metaphorical word play is critical. To do graffiti is also called “bombing,” a word used to connote the aggressive taking back of city spaces that some graffiti writers enact.

Portuguese artist Mario Belem’s “Je ne Regrette Rien,” an homage to chanteuse Édith Piaf, can be read as a manifesto for street artists and graffiti artists who produce on the street with the acute knowledge that their work may not persist for more than a few days, or even hours. “I regret nothing,” the piece declares, gesturing to the fact that the many months of production, all of which will be reduced to rubble in 2014, are still meaningful.

Pantonio’s flying/running rabbits, which also dashed across the exterior of the tower, creating a connective tissue between inside and outside, were one of my favorite elements of the project. The fluid motion was mesmerizing, and seemed appropriate given the scene of destruction (floor boards torn up) around the creatures, also pointing to something more sinister: the rabbits flee. From danger, from imminent destruction, perhaps from the patterns of urban renewal and revitalization that uproot and push out the very residents who used to inhabit Tour 13 and its surrounding structures.

A destruction-aesthetic figured in many of the apartments. Appliances filled with waste, paint cans, or foam, and floors entirely removed or reduced to dust implied immanent elimination. Katre’s room, which was covered with photographic images of architecture, lines extending from the images across the ceiling, and a breakfast table replete with a radio, glass and plate and surrounded by rubble referred to life interrupted. The radio suggests some of the rubble aesthetic of postwar East German cinema, but also the wreckage that continues to proliferate in the wake of acquisitive neoliberal agendas.

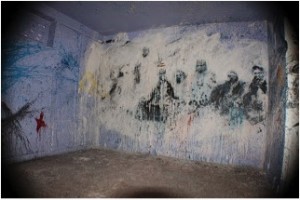

The ephemeral as haunting and haunted space was embodied by Tunisian artist Dabro. His figures, barely distinguished from their background, emerge as ghostly whispers from the walls. They suggest the erased histories and lingering memories of the building’s residents, or his own memories of home, laminated onto the space of Tour13.

Inti Castro, from Chile, further draws on tropes of memory, forgetting, and violence. The entrance to the main room has the words “Memorias” in legible typset print. Entering the colorful inner room, one sees a wall violently punctured, but the paint designs are not disrupted. Embedded in the hole in the wall is a photograph of a little girl. Shrine-like on the one hand, the jagged doorway and uneven floor also create a sense of unease, a memory not fully worked through.

Finally, in Brazilian Loiola’s piece, we are placed in intimate confrontation with anxious female figures. One notes “Don’t leave me in peace/alone.” Elements of the apartment (curtains, doors, a radiator, bathtub) remind the viewer of the everyday lives quietly, or not so quietly, lived in this building.

Distinctions between ephemerality, memory, and forgetting begin to emerge. The ephemeral, as the Tour13 website attests, does not necessarily need to be forgotten, it just cannot be tied to physical existence. The forgotten and destroyed, however, are written out historically and physically, as Inti Castro and Loiola’s pieces testify.

Afterlives of Tour13: Ephemerality as Resistance to Precarity

In her recent text, Culture Class, Martha Rosler explores the problematic linkage between artists (who frequently live in precarious economic contexts for production, itinerant in the strongest sense of the word) and the managerial class, white collar workers in the IT industry, engineers, intellectual workers at universities. According to Richard Florida, these two groups, which he refers to as the “creative class,” are linked based on their affinity for the three “T’s: technology, talent, and tolerance,” a link that Rosler suggests is more than tenuous. Pragmatically, both artists and members of the managerial class ostensibly survive based on project-based and self-directed labor. In Florida’s formulation, such an arrangement is the result of a kind of freedom to choose one’s work, enabling “creatives” to remain unentangled by extended obligations and able to pick new endeavors, a kind of dynamic ephemerality of labor. However, as Rosler reminds us, such a conflation contains the seeds of its own demise, insofar as the labor economy that maintains white collar work supports neoliberalism, an agenda that has “created a capitalism that eats its young.”

The 2011 Occupy events reminded urban citizens that space should be shared and radically public, protesting against the broad-based precarity that is naturalized by a neoliberal economic and social model. In France, where high unemployment numbers and economic slowdown have reinvigorated debates about the place of social welfare governance, this relationship between “creatives” and neoliberalism is not as tight as it is in the United States. Nevertheless, in a city still characterized by an astronomical cost of living that forces laborers, immigrants, and many artists to the periphery, unstable labor conditions (intermittence, lack of benefits, and the nostalgic narrative of the struggling artist who must hold one to four day jobs to support his or her craft) make it so that many artists are priced out of cities. Such precarity is often romanticized by businesses, city management, and media as an emblem of the “creative class” that heralds future growth benefiting all urban citizens, instead of a select few, downplaying the many who cannot or do not survive.

Tour13 affectively and aesthetically intervenes in such debates by engaging in a form of sensorial pedagogy that sensitizes viewers to the distinctions between ephemerality and precarity, memory and forgetting. It emphasizes that public aesthetic space can be shared without being commoditized and reveals the many forms of life, memory, and creative production that take place within and outside national borders, in highly visible spaces surrounding Centre Pompidou but also in dingier alleys in Belleville and in art collectives outside the city in Montreuil or Drancy. By inviting audiences to emotionally engage with work that is condemned to disappear, and giving them a chance to “save” it through memory, talk, and pixel-by-pixel mouse clicks, Tour13 offers a scene of urban pedagogy where the temporary is not reduced to the forgotten.

* *

Images: Caitlin Bruce

[ + bar ]

Grace: Alexander Maksik’s A Marker to Measure Drift

Jennifer Croft

I knew that I had shattered the harmony of the day, the exceptional silence of a beach where I’d been happy. Then I fired... Read More »

Dubitation (a selection)

Martín Gambarotta Translated by Alexis Almeida

Here, the water is different, the artichoke

leaves are different, everything is

in essence, different,

but he who takes the bottle from the refrigerator

and... Read More »

The Red and the Black

María Gainza translated by Jane Brodie

I’m scared. I’m sitting on a plastic chair waiting to see the doctor. It’s a cold spring morning and I’ve come... Read More »

Antonio Machado: Covers by Daniel Evans Pritchard

ALONG THE DUERO

A stork at the bell tower’s peak circled around its height and around the home below as the little swallows squealed. Dry winds have crossed a... Read More »

sending...

sending...