Passages: My Art as an Everything

Natalia Brizuela on Nuno Ramos

translated by Andrea Rosenberg

“No sé.” “I don’t know.” That’s the response Tintin and Captain Haddock get from the inhabitants of the Andean country—vaguely reminiscent of Peru—where they’ve traveled in search of their friend, Professor Calculus, who has been kidnapped and taken there by the last descendants of the Incas. Whenever Tintin and Haddock encounter someone—all of them with indigenous features—and ask if they’ve seen their friend, the natives respond, “I don’t know.” That “I don’t know” is the resistance of the colonial subject. That negation is the power of the powerless: “You can arrest me, you can interrogate me, you can torture me, you can exterminate my people, but you can’t make me talk.” Today the phrase arrives on the shores of the Río de la Plata in the form of an embodied echo: we might, with that phrase, trace a lengthy genealogy of resistance and struggle in Latin America, from the colonial period through the terror of the dictatorships of the twentieth century to today.

Here, a few pages of Tintin serve as a springboard for Nuno Ramos’s installation of sound and performance. Tintin, the young Belgian reporter and explorer who took his readers along with him on adventures in the Congo, Latin America, Egypt, China, India, and dozens of other places, was, through the numerous translations produced, a childhood fixture for millions of children in the last century. Tintin’s travels and adventures around the world are the product of a Europe in self-aware decline, a Europe whose centuries-long period of colonial control and exploitation of vast swaths of the earth was beginning conspicuously to fall apart. For that Europe, Tintin offered a sort of fantasy of its own life after death, the transformation and translation of the most brutal and violent legacy of modern times into “child’s play.” While no adult can doubt the imperialist ideology behind Tintin, for millions of children he offered History in the form of a fantastical adventure. For Nuno Ramos, philosopher-artist-writer, Tintin is not just a reminder of childhood but one of the quintessential sites of reading, of imagination, of exploration, and, in this case, of an activation of and movement toward the political realm through art.

“Passage,” “poetic simultaneity,” “latency,” “constitutive vacillation,” “a hybrid form,” “my art as an everything”—thus did Nuno Ramos himself describe his multifaceted artistic practice a few years ago. Films, sculptures, installations, paintings, performances, music, literary works that all echo one another. A single title, a single name, a single figure, or a single idea that is repeated, in passage from one medium to another, from one material to another, in an artistic endeavor that has since the end of the 1980s been necessarily hybrid.

Nuno’s art is never a single object, a single material, a single instance. Everything he does remains in a state of latency, ready to be retrieved, to reappear, to live again. Hence the title of one his most paradigmatic books, Ensayo general. Everything in Nuno is a rehearsal; we never view the definitive version. This is also the case with our “No sé”: it was first presented in Guatemala in mid-2014; now, we are witnessing a new version, revivified by the rich texture of the local context. The performance will be recorded, and at some future date this material will be turned into a film—probably one with the same title. As the days pass, the sound-filled garden will be transformed into a passage toward death.

The material of the world enters Ramos’s universe as if it were in an alchemist’s laboratory: thus, the mutation and transformation of the material and, closely linked, abandonment and death are two of the core themes of his poetics. Some of his favorite materials are:

Lime

It was at the end of the 1980s that Nuno Ramos, then a young painter, took his art beyond the pictorial frame and began to explore space, matter, and mutation in installations of what we now clearly know to be the expanded field of contemporary art. The vehicle or material that allowed him that departure and expansion, the instrument of his shift toward another artistic practice, was lime. This happened in a show called Cal in 1987 in Rio de Janeiro: the gallery space was shared by a series of constructions of lime: a heap of lime and canvas; wooden columns 1.8 and 2 meters tall, filled with lime; a “sail” made with lime and canvas. Into the early 1990s, lime was one of Ramos’s favorite materials in his alchemical laboratory: mixed with other materials such as cotton, paraffin, and tar, it created shapeless masses of matter that spread across the floor as grime, mounds very reminiscent of garbage [Pele 1 (Homenagem a Carlos Parana)) and Pele 2 (Para Frida)]; as words, a sort of writing in lime, to literally give body to the poetic and exploratory words of Nuno the artist, who is also a writer [Canoa]; and as a title for installations that explored the mutation and transformation of material without using lime as one of their materials [O pó da cal queima o pó do corpo].

Here, in no sé (El Templo del Sol), the body leaves its mark on lime, as the artist had already done in the series of photographs included in the book Minha fantasma. A white, ghostly body: a body that straddles the boundary between being a body and ceasing to be one, a threshold between living and dead matter.

Films

All of Nuno Ramos’s films, including the three being shown at the Parque de la Memoria, have a correlate or “poetic paraphrase” in visual art: Luz negra and Casco were exhibitions, and Illuminai os terreiros an installation. In a sense, it is easy to think that they function as a documentation or record of visual work, because in effect they are. In them we see the work’s process, its staging, its drift, its transformation. But we should not think of Nuno’s films as documentaries: they are not there merely to instruct the spectator on how Nuno Ramos’s art comes to be. The films are films; they are works of art themselves.

Let’s take Casco, for example. The first sculpture with that name is from 1999. An enormous mass of laminated wood, with a shape analogous to that of a ship’s hull, embedded in a large rectangle of burned and compacted sand. That first hull has a subtitle: the name of polar explorer Shackleton, whose ship, The Endurance, became trapped in the ice. In 2004 Casco returns, but it is different now. It began as a performance on the beach in which three characters recited texts written by Nuno as the tide rose. As they spoke, the characters also cut up small wooden fishing boats and fit one boat inside the other, destroying and reconstructing the hulls. As the tide rose, the ships and their destroyed hulls looked like the remains of a shipwreck. All of this was video-recorded, and the film was made based on this material. Later, some of the shipwrecked hulls served as sculptures for the exhibit Cascos at the Banco de Brasil Cultural Center in São Paulo. These wrecked hulls were covered in tar, emerged from sheets of tar. Others, made of compacted sand, were not included in the recorded material for the film.

The films are the last mutation, the final iteration in the alchemist’s laboratory, so that the substance returns eternally as a filmic image, as a ghost of itself. They are the continuation after the end. They are what survives. What continues to arrive afterward.

Sound

With the arrival of the new millennium, sound—like music, like noise, and like song—appeared in Nuno Ramos’s art. In this exhibit, sound emerges from the bowels of the earth, issuing through underground speakers, forming an interrogation whose questions are simultaneously both meaningful and meaningless, banal and metaphysical, concrete and abstract, and their goal is to apprehend the body, to restrain and expose it. In Ramos’s 2002 sound installation Luz Negra (Para Nelson 1), the sound issued from a series of graves, now covered and filled with earth, that contained massive speakers that reproduced the voice of Nelson Cavaquinho singing “Juicio final.” In that first sound installation, as in this one, it is soil—as an organic material but also as a metaphor for the world—that speaks, or questions, or sings. In both, the voice is disembodied, obscene in that it is literally off-scene and also sublime. Soil, haunted by the dead, composed of dead and decomposing matter—which allows it to regenerate and gives it life—speaks to us, will not leave us be. Sound, in Ramos’s work, emerges from an earthly beyond, from beneath the material—sometimes, as here, from soil, but also from salt, from water, and from hay [Vai, Vai] or from within furniture and statues [Grave, grave; Tenho sede]. The voice in particular, and the sounds in general, return from the beyond. They survive all destruction—that destruction that is so constant and fundamental in Ramos’s work. They are what remains and what always is. The return of the voice from death and, in that sense—but also in other senses—the voice once more.

Language and Writing

Nuno Ramos is an artist and a writer, and the two undertakings are inextricably linked in his work. He is, then, a writer-artist, or simply a contemporary artist, for whom the material or the medium in which he works cannot be identified. This became quite clear with the publication of his first book, Cujo, in 1993. Reading that text is like being in the artist’s studio, which by that point already more closely resembled an alchemist’s laboratory. In his installations and in his writing, Nuno, like those philosophical pseudoscientists of old, investigates the material composition of the world, the transmutation both of matter and of the soul. In no sé (El Templo del Sol), we hear a dialogue or an interrogation between an absent voice and the voice of a body that is in the process of being transformed into a ghost made of lime. I distinguish between words—language—and sound because words are important in both their material and their sonic qualities. That is why we hear “No sé” and see it written in charcoal on the wall. That is why the words of that first book, Cujo, appeared as material things before becoming mere symbols, in installations in the early 1990s: forms written with lime, with petroleum jelly, on the floor, on the walls. Words acquire bodies. Words in Nuno’s work always have bodies: they are objects and they are symbols.

It is the verge or the boundary, the place where materials mingle and blend together. That same boundary appears in Nuno’s most recent work. It is perpetually in motion, resisting clear demarcation, preventing the viewer from clearly distinguishing between one material and another, between one state and another. It is the boundary of the indistinction that marks today’s aesthetics. It is also, and perhaps primarily, the far boundary of the world.

* *

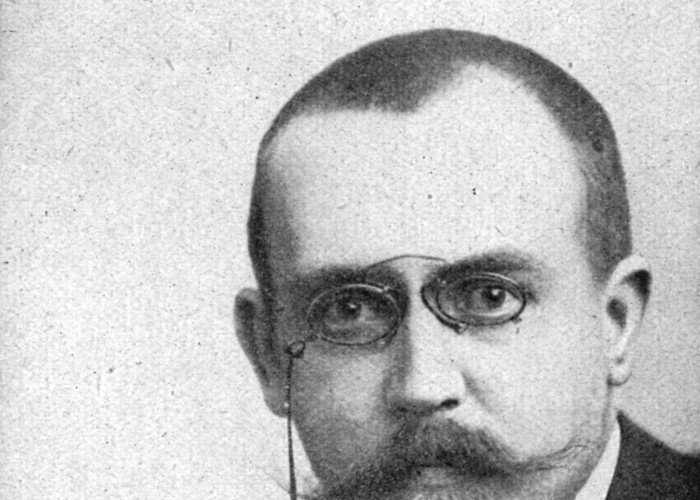

Image: from the video “Casco” (2004) dir. Nuno Ramos, Eduardo Clima, and Gustavo Moura.

[ + bar ]

Junot Díaz: “We exist in a constant state of translation. We just don’t like it.”

Interview by Karen Cresci

Read More »História de amor

Bernardo Carvalho

1.

Antes mesmo de ele completar dez anos, a mãe já o obrigava a acompanhá-la até o cais para negociar o peixe que os homens traziam de... Read More »

Die großen Bäume. Eine Juno-Novellette.

Paul Scheerbart

Die großen Bäume tasteten mit ihren langen Astarmen immer heftiger in der Luft herum und konnten sich gar nicht beruhigen; sie wollten durchaus... Read More »

Primavera – Fall 2013: Tongue Ties

This first quarterly issue of the Buenos Aires Review boasts new literary works from a variety of tongues—French, Galician, German, Portuguese, Russian, and a touch of Hungarian accompany... Read More »

sending...

sending...