Alternative Scenarios For Lovers

Szilvia Molnar

1. I come home to a burnt-down house in Lund. You’re back in Malmö. I’m watching my parents gather half-scorched photographs in the garden, like raking autumn leaves before winter. Their faces are covered in soot. In despair, I take my dirty luggage from the island of Nagu to Russia, where there’s neither emo nor emotion left to feel. In St. Petersburg I buy a typewriter, one of those Smith Corona’s I’ve always dreamed of and I steal a stool from a hardware store. I choose a busy street and sit down to type. People walk by and ask me for a quote, an affirmation or a recipe for princesstårta. For the recipe I make sure to add There’s no princess without the marzipan. In exchange for my typing people leave me their lunches but I rarely eat them because there’s just too much meat in them. Buns with flakes of bacon or thick parsnip soups with pork bits sinking to the bottom.

One morning I meet a dog with a mission. He doesn’t look like a scoundrel, just like a humble mutt. I try to give him a bacon bun but he politely turns it down, claiming that he’s a vegetarian. Tell me more I say and he begins a story of how he was first a Swedish Portuguese man but turned into a dog when he lost his girl. I walked from a town called Malmö, where falafels were reborn, to St. Petersburg. Emo is banned here. On my way I stopped by Budapest because you see this girl is from the land of paprika and watermelons, I figured she might be craving some, but she was nowhere to be found. When this dog, a mutt with savaged paws, said this to me I wanted to embrace him because I finally recognized him as you. And you had been missing me so much that you had forgotten what you were looking for. But I had to only remind you.

OR:

2. I live on the other end of Sweden from you. Years have gone since we last saw each other. Since those ten days in Nagu. You read an ad in the paper. An old lady feels that she will die in a day or two but she has no relatives to inherit her cottage. You decide to call her because the cottage is called Bolond (‘crazy’ in Hungarian). It’s a word you’re familiar with. She takes a liking to you because of your honest face. When she gives you her keys, they feel heavy in your hand but the weight is a comfort. Good things assured to come.

You dust off the sign on the house, stack up chairs to leave more room on the floor, clean the windows inside and out. You’re expecting company even though no one knows where you are. There’s a festival about to happen, or is it New Year’s in a couple of days? It’s something for you. Something makes you get up earlier one day. Makes you shower and shave. Floss your teeth. Cut your toenails. Prepare a meal. Light a candle. You’re practiced at waiting.

After the second knock you open the door.

OR:

3. I’m a cyborg. You’re my charger.

OR:

4. There is a lighthouse not many people know about. Actually, only two people in the world know about it. One of them (me) lives in this lighthouse, the other one (you) comes to visit. You sail in on your boat and find your way only through the light of the lighthouse. I know which days you come by the calendar I keep. My days with you are marked with an H, like a ladder with just one step, H. I climb my stairs and hit the switch. I can’t see your boat but you can see the light. We haven’t talked for years. Solitude at sea and loneliness on the lighthouse have made us mute. Instead we let the diaries speak for us. We exchange them when we meet. They catch us up on the things we missed. They are the loudest words we’ve ever read. Whose voices are we hearing?

OR:

5. Years from now I jump on the bus and sit down next to a man with a tablecloth for a shirt. I wonder for a couple of minutes if it’s you but you get off the bus before I dare to ask.

OR:

6. You’re past being middle aged but people still find you handsome. You live with your wife and 17-year-old son in the outskirts of London. Your wife was diagnosed with MS years ago and her pain has slowly dragged itself into you. You teach Hungarian and Linguistics at a prestigious university but with weariness since the students don’t seem to care. Occasionally, you spice things up during class to make them wake up. You tell them about nivkh, a language that isn’t truly related to any other language but nonetheless is included in the Paleosiberian language group. You show them on the map how they spoke it here, in Outer Manchuria, but all we have left are tapes, and then you point at the five black tapes on your shelf. The students look at you with their heads tilted to one side. No one is getting through to anyone. Then you see my face. From your small crowd of students (because who wants to study Hungarian these days?) you see me looking at you like I’m brooding on a question. But I won’t ask it in class today.

Then, over the course of a couple of weeks, contact occurs. You teach, I listen, I ask, you explain some more. You pass out handouts with my interests in mind and I’m not afraid of questioning your theories. From handouts we move on to books. You give me Frost, Didion, Brautigan, and Edna St. Vincent Millay…I pass you Boye, Tranströmer, and Södergren. We try to meet as often as possible without it looking suspicious to anyone else in the department, but it never really feels enough. Some weekends we go to the British Library as soon as it opens and sit at a booth with our work until the last lines can be read before closure. You bring me Chinese pears that look like apples but taste like sweetened water. I bring us dark bitter chocolate.

Suddenly, the months have moved past us. It’s time for me to graduate and it’s time for you to plan another academic year. We agree to keep on meeting, but we don’t even get to a third lunch because your wife calls me. She found my name in your journal and cries out that I’ve ruined her marriage, her life, a family I shouldn’t have tinkered with. I realize my selfishness and end all contact with you. Unwillingly, you stop writing to me too.

Five years on and we’re still not talking.

OR:

7. You have settled into your apartment in Värnhem, Malmö. Some days you drive a postal truck and most nights you make music. I have moved into a room in Södermalm, Stockholm. Most of my days and nights are spent reading and writing. But my place is completely empty so I’m forced to start over from scratch and do the most adult thing in the world: Buy a bed. Due to my financial situation, I turn to IKEA for a solution. I walk through the entire floor, stop at the bedroom department and test-sleep each mattress. The firmest one has convinced me; I decide to buy it. I walk down to the pick-up aisles and find my 50 kg mattress. I schlep it all the way to the cashier and there, I’ve done it. I’ve bought my first adult bed. It’s bigger than a single bed, but smaller than I’d like. It’s the size that would give us enough room, should you ever come to visit.

I stand in line for the transport service and look at an ugly baby in the arms of a stressed-out mother. She is worried that her pastel sheets won’t match the wallpaper in the bedroom and can’t seem to find a closer shade. I count to ten because I’ve heard that helps if you’re angry, but it doesn’t work. Instead I try to stop looking at the ugly baby. That helps somewhat. I put in an order to have the mattress shipped to my new place. The big-bellied man behind the booth says that the bed will arrive the next day. I prepare myself for the arrival of the bed. I dust my shelves, I water my plants, and I line up my books in a row. Then, the bell rings from downstairs. A familiar* voice tells me my bed has arrived. I run downstairs to see you sitting satisfied in the IKEA truck. Turns out you are a driver of all kinds of trucks.

OR

8. I make up stories.

[ + bar ]

The Red and the Black

María Gainza translated by Jane Brodie

I’m scared. I’m sitting on a plastic chair waiting to see the doctor. It’s a cold spring morning and I’ve come... Read More »

John Freeman

THE HEAT

At night as the heat’s warble strummed to a ticking silence, and the crabgrass turned blue then green then black, the branches above would relax and gently pluck my window-screen, like the dark-haired woman who, years... Read More »

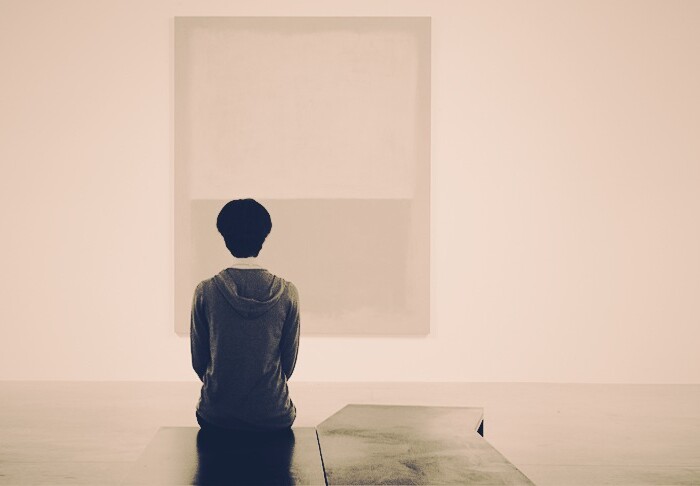

The images featured in BAR(2) were selected by Marisa Espínola and appear courtesy of:

Espacio en Blanco www.espacioenblancocultural.org

Espacio en Blanco began in Buenos Aires in 2009, when writer Francisco Moulia and... Read More »

The Riverbed

Carol Bensimon translated by Adam Morris

They so happened to be born in a rather small town between two more or less larger ones, something they couldn’t get used... Read More »

sending...

sending...