Bellatin and Japan: an Interview

Mat Chiappe

translated by Anna Hardin

Mario Bellatin once said to me: “I don’t want to go to Japan.” I don’t know if we went on talking about something else or what happened, but I never got a better explanation. And so, when I was presented with the opportunity to interview him specifically about the relationship between lo japonés and his literature, I decided the most important thing for me was a response to that statement. I prepared a long list of other questions (as you’ll see, all useless), dressed as seriously as I could, stowed my computer in my backpack, and took the metro to his house. I rang the doorbell and waited until, from the other end of a long hallway, the author, filmmaker, lecturer, and translator appeared.

“Hello, Mat,” he said, holding back his dogs, “come through here, I was just making some passionfruit juice… have you noticed you can’t get it here in México?” I nodded, without mentioning you can’t get it in Argentina, either. We went into his house, the interior fluctuating between minimalist and colonial. I sat, played with his dogs, talked about how my studies were going, about his life, a recent trip, his son Tadeo, the teacher’s strike in the Zócalo, that he owed me some gnocchi. “Next time for sure,” he declared. I was a little nervous; I had seen him many times before and in more interesting situations than an interview; I don’t know why I felt perversely professional this time.

Because I’m scatterbrained, without even opening the computer I had planned to record him with, I blurted out the stupidest and most predictable question possible while he served me passionfruit juice: “So, Mario, which works of Japanese literature do you like most?” He gave me a long list, from which I remember House of the Sleeping Beauties by Kawabata and Woman in the Dunes by Kōbō Abe as the best. “The first is simply fascinating, stunning, the scenes that pass one into the other in that closed room, as if in a camera obscura… and the other, I still feel the Kafka-esque anguish of that sand they can never stop moving.” He asked if I had read A Pale View of Hills, Kazuo Ishiguro’s first novel. “No, should I?”… “Another gem… a woman in England remembers her past in Japan during the war, and the pre-war years, that other Japan, lost in time… Then, that’s all lost, and the text transforms into a typical European novel until the end.” Silence. “I don’t know what you’re doing here, you should go read it now.” He smiled.

He talked for a long time about how rootlessness, the memory of that ancient Japan, the traditional pre-war Japan, characterized the Japanese literature he liked most. “I’m also interested in intersections, mixtures, journeys.” I guessed that had to do with his Peruvian-Mexican status, the hybridization, the mixed nationalities. “Ah… I have another recommendation for you.” He reached for my computer. “Yes, yes, let’s watch the trailer, it’s great.” He took the device from my hands. “It’s called Kamikaze Taxi, have you seen it?” No, I hadn’t. “It’s delirious: two friends face off against the Japanese government and mafia: one of them is a doctor living in Peru, who builds a hospital there and then comes back with his Peruvian son; the other is a horrible guy who manipulates the first one to achieve his political ambitions… the craziest circumstances make the doctor commit ritual suicide by seppuku… His son becomes a taxi driver, meets a woman, they flee the yakuza together, she asks him to escape to Peru, to start a new life; he tells her he has a final mission, a score to settle.” I kept quiet. “Terrible,” he finished, “but the very fact that it exists, that someone could make a movie or write a novel or whatever about these intersections, these connections, seems absolutely fascinating to me.” He played the trailer again, and again. Then, the whole film.

He told me about his fascination with Japanese cinema, about Kurosawa and Kitano films, with particular emphasis on Ozu. “Seen anything of his?” No, Mario. “Alright, watch them… with Ozu, everything repeats: in one film a train passes into the distance; in another, the same scene, another train, but with a slight difference; in a third, another train. In another film there will be a family fight; you know what the daughter will say to defend herself, because you’ve seen it in another film; what you’re waiting to see is how the filmmaker will manage to insert a subtle difference in this one.” I recommended a film to him: Paprika. “Tsutsui Yasukata wrote it, the author of…”… “The one who wrote Salmonella Men on Planet Porno, yes, I loved those stories, the one about the bonsai that causes erotic dreams in those who sleep next to it is almost as Borgesian as it is pop.” Then he put on another trailer or some music (I don’t remember which). “Give me more things from Tsutsui to read, Mat, he’s brilliant: his perversions, his deformities, his strange, insecure bodies; it’s a really bizarre mixture.” I noted all this mentally. “And if this were possible… in a good translation, you see how it really is all there.”

Immediately, I pressed him to expand a bit on the subject of translation. “It must be so hard to translate Japanese literature to Spanish… yes, you’re totally insane.” (Indeed, I study Japanese and plan to translate someday). What he said was that “it’s like two worlds, a ‘there’ and a ‘here’, which are moreover fictitious, because underneath is something that unites us… it’s like two worlds created by language, and when you try to bring them together something is left over that can’t be said, fuzzy boundaries.” “You don’t have to be so politically correct, I’m not recording you.” “Ah… what I mean is that Spaniards translate like animals,” he concluded. We brought up words like gilipollas, chutar, sabéis, os, and so on. “They have nothing to do with us Latin Americans.” Then he brought up names I never thought he would know: Atsuko Tanabe, Javier Sologuren, Guillermo Quartucci, others I’d never heard of, a long list of Latin American translators and academics who specialized in Japan. I took the opportunity to interject Mexicans like Tablada and Paz, and Peruvians like Arguedas and Vargas Llosa, each one of whom included Japanese characters, elements, and themes in their works. I don’t think he liked the comparison at all, though he acknowledged he was closer to the phantasmagoria of the first set than the realism of the second. He returned to the subject of translation. “Octavio Paz was another awful translator… he could translate one measly haiku into fifty of his own lines.” We talked about Liliana Ponce, César Aira’s wife, who translated Murakami from the Japanese. “In terms of the translation, everything got worse when they started bringing in a lot of Kenzaburō Ōe… from then on, it was a total disaster.”

I asked which of his novels should be translated into Japanese tomorrow. He answered with the titles of those which made explicit reference to Japan: his Shiki Nagaoka: A Nose of Fiction, Illustrated Biography of Mishima, Mrs. Murakami’s Garden, and The Notary Clerk Murasaki Shikibu. The first is an apocryphal biography of a Japanese writer who immigrates to Peru and is tormented by his monstrous nose. The second narrates the wanderings of the decapitated ghost of the writer, soldier, and bodybuilder Yukio Mishima. In the third, the widowed and resentful Izu insists on having betrayed her artistic ideals in her youth, destroying her beautiful, traditional garden. The final novel relates the transformations of a Mexican writer into various others, including the author of the now-classic first novel in the history of literature: Murasaki Shikibu.

He served me more passionfruit juice. “Maybe the Japanese don’t want a novel a-la-Japanese, maybe they want something more, uh, Latin American,” I blurted out. “That’s true, you might have to translate a different one.” “What about Beauty Salon? It has just the right amount of Japanese-ness, what with that Kawabata epigraph, a subtle reference to the masterwork we already talked about: House of the Sleeping Beauties.” He agreed. “Just the same, this thing about lo-japonés and lo-latinoamericano seems a little outdated to me.” I asked if he knew, in relation to his novels, that various critics had voiced and repeated phrases such as “processes of decontextualization,” “strangeness,” “mechanisms of defamiliarization” in order to explain his use of elements and themes characteristic of Japan. According to them, Bellatin would use the Japanese world as an example of that farthest from his own culture. “What do you think about that?” I asked. “I don’t know… I just love Japanese literature. Maybe a few of them, when they say decontextualization, really mean escapism, which is ridiculous; this, the other… everything blends together in language.”

This “decontextualization” led to another, somewhat unexpected, topic: he started telling me about Fujimori and his youth in Peru. Regarding the former he elaborated quite a bit, with details, and even compared the former president with a samurai, whom the Japanese gave a hero’s welcome after he fled in 2000. There was Mario Bellatin talking to me about politics, ideology, like those Japanese poets of 1920 who couldn’t just write haiku or tanka like their contemporaries. Hayama and Kobayashi, among others. “My link to Japan also comes from my childhood,” Bellatin told me, or I read somewhere, “most of Peruvian society still has strong anti-Japanese feelings, a product of the U.S. propaganda from the 20th century; all Japanese were potential nationalists, and therefore a threat… So much so that my parents were always embarrassed that my grandparents had hidden a Japanese immigrant during the Second War, and Japanese food was actually forbidden in my house… I’ve lost touch with them now.” Some of his words sounded familiar; more of them I don’t know if he’d said to me or if I’d read them somewhere: “It’s more and more obvious to me that my characters are my other selves… It’s a way of understanding the world: every thing is everything, every thing forms part of everything.”

“But let’s change the subject…” Mario continued, “if you’re interested in all that about ‘decontextualization,’ the best story is Black Ball.” Son of a bitch; I hadn’t read that one, either. How can you interview someone about their links to Japanese culture if you don’t know the text he thinks is most important to this connection? “I didn’t read it…” I confessed. “Ay, Mat, Mat…” he laughed, “it’s about an apathetic entomologist, Endo Hiroshi, who finds an extinct species of insect on an expedition. He keeps it in a box, conserves it, treasures it, but the bug finally turns into a black ball… In the end, he only finds one way to keep it forever, but I’m not going to tell you what it is.” “Sounds like something from Abe, something from Shimada,” I added. “Very much so… although the story’s true significance is something else; come, follow me.”

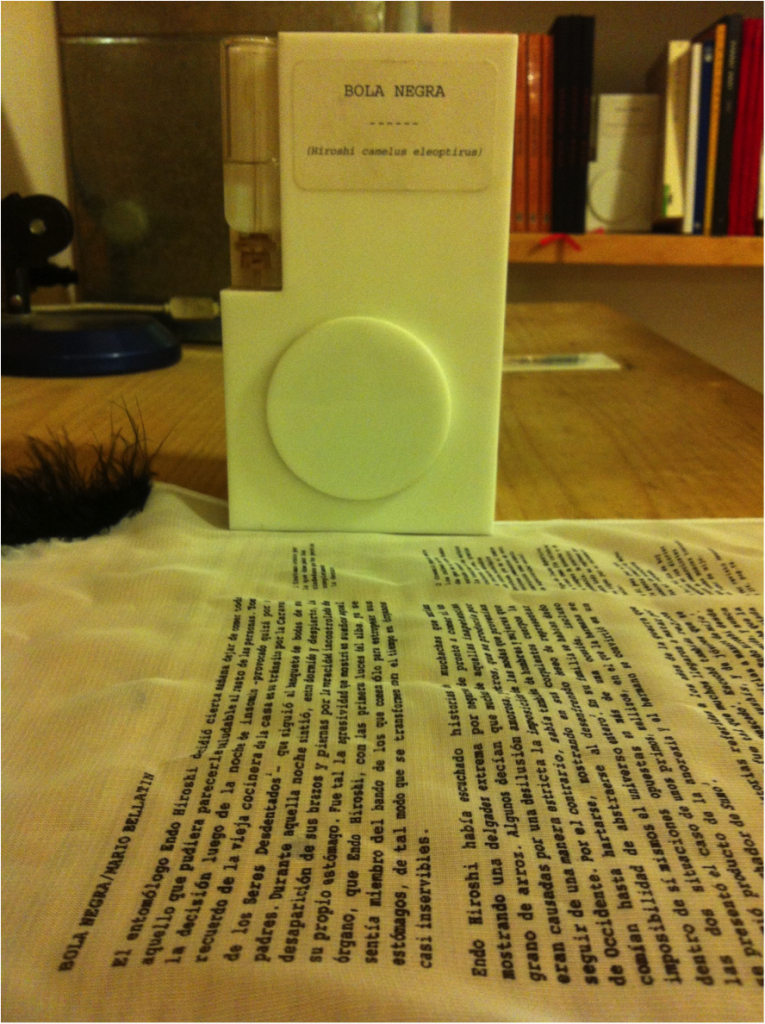

We went to the guest bedroom. On the upper shelves were the first five thousand of the famous Hundred Thousand Books of Mario Bellatin. Underneath was a collection of his making titled Writers of America, two volumes of hollow books in which (he showed me) he kept the first, signed leaves of all the books he had been given. Beyond the occasional title (Rulfo, Tanizaki, Roth), there were no books by other authors. Some were stacked strangely, placed secretively, perhaps on purpose. I got the feeling some kind of ritual was regularly performed here, like the Japanese construction of Shinto shrines, or that popular gift-wrapping practice, furoshiki. Mario moved some books, took out magazines about Japan, his illustrated books, special editions – all a delicate collection of book-objects. Then he took out a small white box and gave it to me. It was the object-edition of Black Ball. It had a vial and a bulb on one side; turning this, a small hatch opened and inside was a canvas on which the entire story was printed. It was the little box of the entomologist Endo Hiroshi:

“Black Ball is going to be a movie now,” Mario continued. “not the same, I don’t even know if it should be called a documentary or a narrative or both.” He reached for my computer again; he put on another short video with images. “The worst thing happening in Ciudad Juárez is the naturalization of horror, it’s deterritorialized, everything’s already somewhere else; horror is the norm… in Black Ball, the musical of Ciudad Juárez, and I want it to have this title, Mat, different from the story’s; what I want to do in the film is decontextualize the decontextualized, imposing a seemingly unconnected story on the city, on reality, to see if the sentences can develop a new dimension and illuminate what’s happening there in another way; new ways of getting close to the facts, of feeling them… A novel that speaks quasi-heroically doesn’t interest me; I wanted to think about what would happen with a group of young people who are part of a choir and want to make an opera there, in the land of a horror that is not only normalized, but also institutionalized and corporatized.” The images continued on the computer, a strange superposition of the hills of Ciudad Juárez, businesses, kids singing. Then I realized that the story about a Japanese entomologist, that self-contained story seemingly unrelated to anything, from the remove of its little artisanal box in a guest room in the largest metropolis in Latin America, was also a symbol for all of México.

We went back to the living room. I stared at my still unused computer and tried to make a mental note of all the names and references and quotes, everything about Kawabata, Ozu, translation, the sinister and political past and present. “Look, Mario… everything you’ve told me is fascinating, but I still have one question I want you to answer, one that I think is behind all the others.” He looked at me. “What is it, Mat?… You’ve gotten very serious.” I told him: “You once told me you didn’t want to go to Japan… I demand a public explanation.

There was another long silence; I don’t know if I’d made him uncomfortable again. He smiled. “It’s simple… I want to maintain my distorted idea of what ‘Japan’ is, a sort of essence, a constructed essence, fictitious and flawed… My interest is in what remains of those ruins, not in their origins… What remains, the residue, what translations leave behind, the mystery, the text, the characters, a whole system of language, and, above all, how this can be transmitted through the centuries—these things are enough for me. I don’t care as much about the reality of Japan as I do about that illusion, or more precisely: how we construct the illusion.” I thought of Severo Sarduy, who said something very similar in relation to India. Roland Barthes also came to mind, and his words upon returning from Tokyo in The Empire of Signs:

If I want to imagine a fictional town, I can give it a made-up name, treat it as a fantastical object, found a new Garabagne, without compromising as such any real country in my imagination (but then this same fantasy is that which I compromise in the signs of literature). I can also, without any claim to represent or analyze reality in the least (here the greatest gestures of Western discourse), take somewhere in the world (there) a definite number of features (graphical and linguistic word) and with them deliberately create a system. I will call this system: Japan.

Mario brought out cuernitos, little pastries we call medialunas in Argentina. More than defending an exotic Japan, the orientalist construction of the West, Bellatin exposes that self-same construction, puts it onstage, tells us that yes, it’s no more than a fabrication, a system, that it is what we can and want to imagine. Those imaginations say much more about us than they do about the other, more about Latin America than Japan, more about Ciudad Juárez than the entomologist Endo Hiroshi, more about the transvestite hairdresser from Beauty Salon than Kawabata’s sleeping beauties.

We finished our snack and I took one last sip of passionfruit. It was night when Mario put on another trailer for a Japanese movie from the 40s. And then I remembered: “Ah, I didn’t even record you.” “Oh, well…” “Don’t complain later if I pull quotes from someplace else and make up an interview with it.” “No worries.” We say goodbye. While I waited for the metro I remembered that form of Japanese poetry, the renga, in which Octavio Paz, Charles Tomlinson, Jacques Rouband, and Edoardo Sanguinetti dabbled. In the renga, a poet improvises some lines, then another provides some new ones continuing the previous themes or words, then another does the same, and another, and seven or eight poets link verses like this until the circle comes back to the beginning. Finally, the copyists of antiquity transcribed what they wanted, and bitter debates arose about who was the true author of the poem. Bellatin himself, in a note for The Nation titled “Kawabata: Embrace of the Abyss,” through appropriation and copy-paste, plagiarized critics and Kawabata himself, using their phrases, quotes, references. This compulsory form of re-writing, which this interview would have to be, was what I discerned getting on the metro, during the journey, arriving home. In the end, as Mario has put it: “I don’t have anything to say, I only know that I want to say something, and to do that I need to create narrative forms.” I opened my computer and wrote all I could.

* *

Images: Sebastián Freire (portraits) and Mat Chiappe (Bola negra)

[ + bar ]

An American Poet’s Dream: an interview with David Shook

Interview and introduction by Pola Oloixarac translated by Heather Cleary

A young professor of literature in Los Angeles collects funding and poems online in order to make... Read More »

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Victoria Liendo translated by Victoria Lampard

To Charles Coustille, guilty of making me love France, he who declares himself innocent of everything.

Libraries very much resemble churches: there are some that can... Read More »

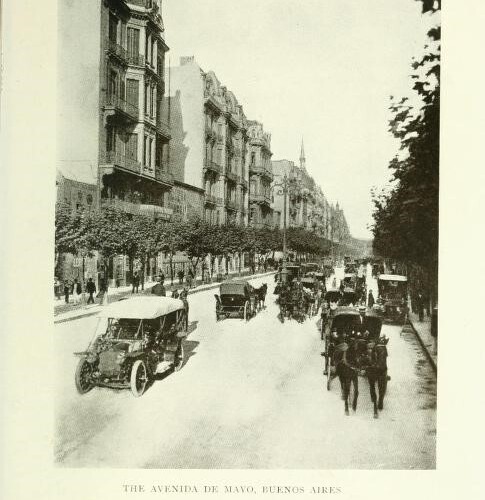

Argentina and Uruguay (excerpt)

Lucas Mertehikian

We don’t know much about Gordon Ross. We don’t know how long he lived in Buenos Aires nor where exactly he had come from. The first... Read More »

O leito

Carol Bensimon

Acontece que nasceram numa cidade bem pequena entre duas mais ou menos grandes, um tipo de coisa ruim para o conformar-se, porque assim tinham toda... Read More »

sending...

sending...