Mario Bellatin: Doubles and Outtakes

Craig Epplin

Y el eco es anterior a las voces que lo producen.

—Nicanor Parra

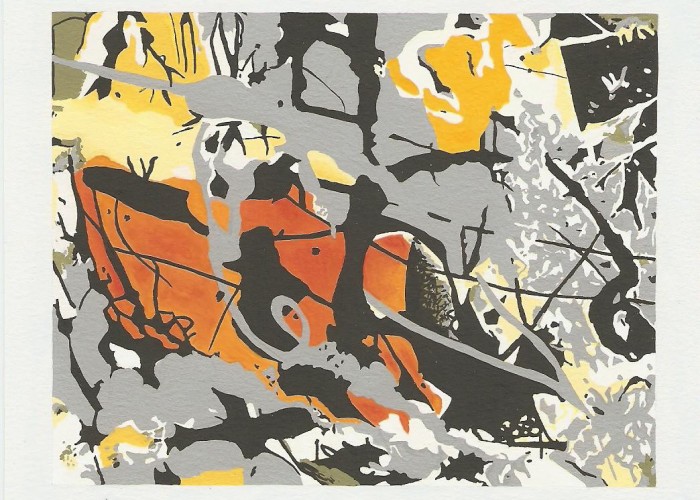

The title of Mario Bellatin’s 2008 biography of Frida Kahlo, Las dos Fridas, is unsurprising, obvious even; of all her paintings, Bellatin chooses one whose resonance with his own literature is unmistakable. Unmistakable because everything in his work seems at once doubled and modified, his endless self-portraits mapping a landscape of dissemination. The name Mario Bellatin, or more often mario bellatin, proliferates, attaching fleetingly to any sort of body, young or old, male or female. One of his most recent books, Disecado (2011), follows the model of a Baroque painting (as Federico Zamora aptly puts it), detailing a somnolent encounter between the narrator and a phantasm of himself. The book feels like an expansive fresco of the literary life of the author, one of numerous volumes in which Bellatin appears not as a specular figure, but rather as simply another being on display. His writing undergoes a similar process, as every new title seems to reinterpret the previous ones.

In other words, copies abound in Bellatin’s oeuvre, though each is slightly different from its antecedent. Every element acts as a correction or addendum to what came before, which is invariably coupled to something else. He employs numerous strategies of duplication, just as Kahlo, in this painting, ciphers various affinities between her two avatars: physical resemblance, biological dependence, the experience of touch, and the casual brush of worn garments.

The painting is one of her most famous. In it, two representations of the artist clasp hands, sharing both a bench and an artery, their exposed hearts alluding to the biological substrate beneath the multiple experience of life. Their faces are nearly identical, with difference inscribed only in their respective dresses: one is clad in colonial garb, while the other wears indigenous attire. Two Fridas and two Mexicos, in other words, linked together by the coursing of blood, blood that ultimately overflows, staining the white dress of the figure on the left. Redoubled identities, along with their excesses, here signal the irreducibility of national culture.

I wonder, looking at this image, what Bellatin thinks about it: whether he thinks about Mexican history when he looks at it, or whether he sees the red, veiny web at the top of each heart as a little hand reaching up to choke the impassively seated subject—a sign, perhaps, of the ultimately sinister designs our bodies have on us. Despite having borrowed its title, Bellatin never discusses this painting, nor does he include a representation of it in his book. Instead, it hovers in the background, like the overcast sky in the scene itself.

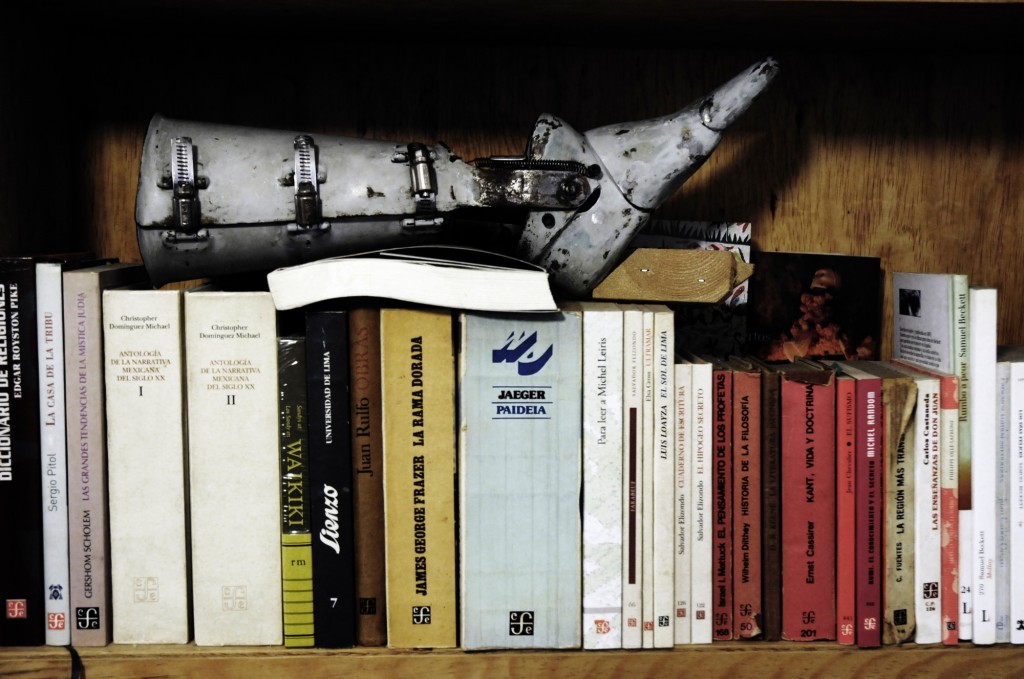

This omission does not indicate an aversion to images. A single photograph adorns each page of Las dos Fridas. These photos seem artificially aged, an effect achieved, Bellatin tells us, by his employment of a toy camera from his childhood. Most of the images chart a trip he took in search of a woman who lives in a small town and sells her wares from a stand at the local market. The woman is not Frida Kahlo, who died in 1954, but she might be. Bellatin is willing to entertain this possibility. At least this is the pretense that grounds the writing of this book.

He describes the circumstances that spawned this unlikely hypothesis in the book’s first pages. When the biography was commissioned, he requested a photograph of Kahlo, which he then circulated among his acquaintances, seeking information about the woman. Most respondents saw the iconic painter and responded accordingly, but one wrote back that he recognized the woman from her stand at the market. Several others later claimed something similar. Bellatin’s reaction, as he registers it, was skeptical but not dismissive: “The information I received,” he writes, “about the supposed existence of Frida Kahlo running a market stand did not seem credible; nevertheless, I was intrigued by the idea that someone could continue living in spite of her death.” His trip is premised on this possibility.

We read about his arrival at the small town. He approaches the market and asks where to find the woman in the photo; his interlocutors snicker and warn him against proceeding. When I read this passage in Las dos Fridas I couldn’t help but think of Pedro Páramo and other quest narratives. Similar moments of sinister foreboding are fundamental to these plotlines. Bellatin plays up this literary parallel, writing that his journey (itself literary from the outset) now mimicked “the regular outline of certain literary works. There always seems to exist an intermediate place where they warn the traveler not to continue on his path.” This point is where life and fiction become indistinguishable.

In spite of this cautionary foreshadowing, the narrator eventually finds the second Frida, the woman who works at the market. She is occupied at her stand and surrounded by assistants, but he manages to carry out an interview through the throng around her. He asks what she knows of Frida Kahlo, the artist. She responds with a succinct biography worthy of Wikipedia—dates, important life events, professional accomplishments, etc. Immediately following this passage, the book’s longest, the narrator tells us that he noticed her reading this list straight from a book hidden in her lap, perhaps a winking fulfillment of Bellatin’s own commissioned task as biographer.

It is a virtual repetition of the dynamic implicit in the Congreso de Dobles, a 2003 exhibition organized by Bellatin wherein various non-professional actors stood in for four Mexican writers, whose presence had been promised in advance. These stand-ins recited memorized scripts, channeling their avatars at a distance. Arturo Valdivia has shown—brilliantly, playfully—how the shadow puppetry of that exhibit coheres both with the strategies of Las dos Fridas—both Bellatin’s book and also, to a degree, Kahlo’s painting. As the second Frida reads what she knows about Kahlo the painter, we become witnesses to an odd scene: Kahlo’s presence is channeled, as if by a medium, but the tangible source of that channeling is underscored, not obscured.

This moment in the narrative recognizes that little up to this point has been directly about Frida Kahlo, at least not in the conventional sense of the word about. I see two possible ways of interpreting this gesture. On the one hand, we might conclude that Kahlo has served simply as a pretext for Bellatin to tell the story of a trip that meanders not in space but in memory: hence the narrator’s extended asides on his dog, friends, and Fascist forebears. In other words, narcissism is inevitable. We are always writing about ourselves, and Bellatin has simply made this unavoidable conundrum the object of his book. The play on identity and presence would be nothing but a device that enables the writer himself to take center stage.

The other way of understanding Las dos Fridas is less obvious, but might shed more light on Bellatin’s broader practice as a writer. This second option holds that the book actually makes good on its promise; that it is, in its way, a biography of Frida Kahlo, despite the fact that most of the narrative is composed of preparations and tangents, that few of the photographs seem to bear a direct connection to Kahlo or her world, and that the author takes palpable pleasure in leaving most of the standard biographical details for the last few pages.

Bellatin’s approach, then, directly engages the genre of biography and its assumption that a life can be reduced to a sequence of events closely tied to the displacements of a body, arranged chronologically and retold as a linear narrative. In this genre, birth and death provide the framework for family and professional engagements, political action and civic ambitions, and the passage through various institutions. We know, however, that life does not proceed in a vacuum, which is why the best biographies allow us to relate an individual destiny to broader historical forces.

Bellatin insists on this last point, amplifying it, not only in his own, varyingly autobiographical narratives, but throughout the entirety of his work; one strand that unites these texts is their tendency to take the notion of context to its extreme. To stick with the present case, he has decided, in Las dos Fridas, that the mystical path of his friend is somehow relevant to the life of Frida Kahlo, as are the Fascist beliefs common both to his own ancestors and to an isolated immigrant community in rural Mexico. Those are just two instances in a book that is full of such asides. By including so many seemingly unrelated narrative strands in this biography, Bellatin seeks to erase the lines that separate a given life from others and, indeed, from everything else.

That said, the inclusion of these stories is not entirely arbitrary. They emerge successively from the process Bellatin describes at the outset: the circulation of the initial photograph and the road trip that ensued. This process becomes a sort of method, whereby Bellatin seeks to approach his subject through the paths opened up by one manifestation of her image in the present. This method seeks to destabilize the basic unit of biographical writing: the neatly delineated life. In place of this rigid notion, Bellatin seems to propose that a life always extends outward, that it glimmers and reverberates in unexpected places. A project like Las dos Fridas, like much of Bellatin’s work, tries to uncover those places. The background becomes the foreground. Or, to draw out another cinematic analogy, if the traditional biography is a cleanly edited film, Bellatin would rather sit and watch the outtakes.

In other words, if life indeed extends endlessly beyond all limits, then Bellatin sees the task of the biographer as that of hearing the sudden echoes and revealing the subterranean traces of the dead through controlled situations, artificial scenarios. This is biography as séance.

The results of such an operation might turn out to be banal. They might devolve into the brand of narcissism I mention above. Is this a weakness in Bellatin’s method? Maybe, though perhaps it owes more to the fraught nature of the biographical impulse itself, based as it is on the slippery task of delineating a life. And also to the fact that this task has grown even more daunting in the present, when our likenesses proliferate widely, a point that Bellatin underscores toward the end of Las dos Fridas when he photographs a pair of Chuck Taylors silkscreened with the face of Kahlo herself. In this media ecology, traces of the dead—and the living—surface with or without the séance of writing.

Everything becomes outtakes, in other words. The reel is endless. And some of it is even compelling.

* *

Images: Photograph by Sebastián Freire; Las dos Fridas via Proyecto Kahlo.

[ + bar ]

Cardenio (excerpt)

Carlos Gamerro

They lived together on the Bankside, not far from the playhouse, both bachelors; lay together; had one wench in the house between them, which... Read More »

Good Enough for Jesus

Russell Scott Valentino

“If English was good enough for Jesus, it’s good enough for me.” —Texas Governor “Ma” Ferguson (apocryphal)

He doesn’t want to say the wrong thing. Who knows what... Read More »

Rowan Ricardo Phillips

TO AN OLD FRIEND IN PARIS

I haven’t seen the ghost of your mother. But I have seen your poems about the ghost Of your mother as she brushes by... Read More »

The Ceremony

Inés Marcó translated by Alex Niemi

CAST

Pope Layman Guard of the Brotherhood Brothers of the Circle

The characters meet at the entrance of a large urinal. The Pope is... Read More »

sending...

sending...