Travelers to Buenos Aires

Lucas Mertehikian

translated by Jennifer Croft

The history of the Americas has always been inseparable from the notion of travel, and Argentina is no exception to this rule. In fact, the history of Argentina’s literature can only be understood in connection with the men and women who arrived at its shores from far-off lands and wrote about that very experience.

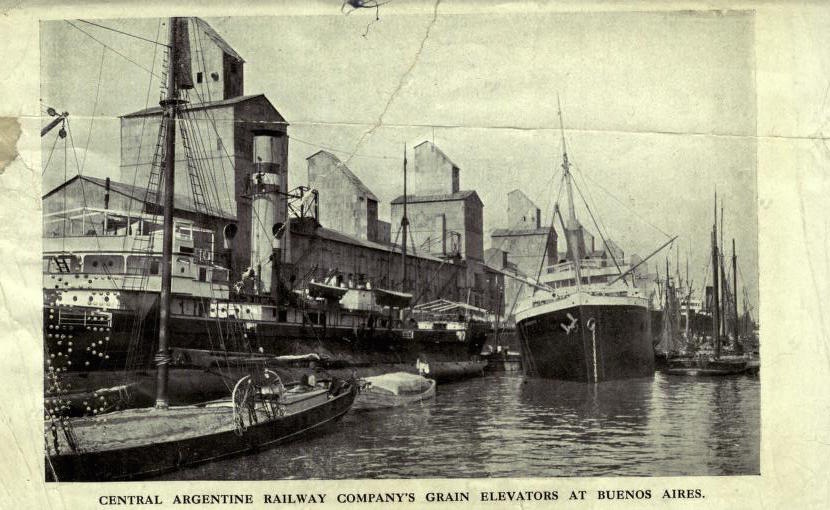

No sooner had Argentina declared its independence than it began to see travelers—many of them from Great Britain—looking to try their luck and explore the commercial prospects of the new nation. The country’s vast plans captivated this multitude of newcomers who, with their aesthetic sensibilities that tended to fall somewhere in between the naturalism and the romanticism of the era, documented this astonishment in numerous books.

Adolfo Prieto has suggested that it was those books that led the first writers of the young republic—like Sarmiento, Alberdi, Mármol—to the landscape that would become the foundations of Argentine literature. Then, in the twentieth century, a new breed of celebrity travelers, like José Ortega y Gasset, made their way to Argentina to celebrate the nation’s centennial in 1910 and didn’t stop coming after that. Those “cultural travelers,” as they’ve been called by Gonzalo Aguilar and Mariano Siskind, constitute a cornerstone of early-twentieth century literature in Argentina. The local intellectual and artistic circles eagerly awaited them and heatedly debated both them and their works, all the while hoping they’d be able to provide an answer to the same question Argentina’s earliest authors had asked themselves: what are Argentines?

Between those periods, in the 1920s, there was also another type of traveler to Buenos Aires, coming from Europe and the United States. Neither trailblazers nor celebrities, though some enjoyed a certain notoriety in their home countries. They were not anticipated by the Argentines with any particular eagerness, nor given a particularly warm welcome.

Perhaps because of this, with only a few exceptions, their writing has yet to be translated into Spanish. This series from The Buenos Aires Review aims to revive four of the authors from this in-between category and resuscitate their writings on Argentina: John Foster Fraser, Gordon Ross, Katherine Dreier and John Alexander Hammerton, in that order. Joining these four is Jules Huret, who was translated from French into Spanish at the time by Guatemalan writer Enrique Gómez Carrillo, but these translations have been widely neglected until now.

The chronicles we’ll be presenting here were published between 1914 and 1920. We are interested less in establishing a core Argentine identity than we are in enriching this question with the potency of history that the rereading of these texts, a hundred years after their original publication, demands be taken into account. What, in other words, have Argentines become?

Read the first entry in the series

Read the second entry in the series

[ + bar ]

The only happy ending for a love story is an accident (excerpt)

Hyperion [moscow]

By Marfa Nekrasova translated by Nathan Jeffers

The word Hyperion has many possible meanings; it can refer to a book, a poem, a tree,... Read More »

Luna Miguel

YOU HAD GLITTER ON YOUR FINGERS

I can hug the old refrigerator before they take it away. I can write that you had glitter on your fingers and that burning glitter... Read More »

Among the Dead

Ernesto Hernández Busto translated by Heather Cleary

The future is always a lie. We have too much influence over it. — Elias Canetti

I.

It all began... Read More »

![Hyperion [moscow]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/DSC06622-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...