Evita Fashionista

Mariano López Seoane

translated by Heather Cleary

A decade ago, the New York philosopher Jennifer Lopez gave us “Jenny from the Block,” an ode to upward mobility in the key of bling. In the hook, she syncopates what would become a mantra of the mamis of global latinization:

Don’t be fooled by the rocks that I got / I’m still, I’m still Jenny from the block.

In fewer than twenty words, Jenny gave FM hip-hop not its social truth (it had been clear since the 80s that a main theme of the music would be gaining access to consumer goods that had previously been off limits), but rather a possible political stance. The single, released at the Everest moment of Jennifer Lopez’s ascent into the pop firmament, is meant to turn her power into something not only recognized, but also accepted. Miss Lopez tells us: I don’t just want to sell millions of albums and call shots in the complex world of the entertainment industry. I also want to have authority among the masses—not the Machiavellian authority of an ice queen, but the esteem of a benefactress. To rule not by terror, but love. In these two lines, the star gives herself over to a populist strategy we know all too well: she acknowledges that she is nothing without her followers and, in a manner shaped by the ethics of street cred, she sets out to forge allegiances and inspire the active support of her audience. In the key of politics: she takes a page from hegemony’s playbook.

Eva Perón could have opened a manifesto on gender equality with these very words. In fact, there are nearly identical phrases in My Mission in Life (La razón de mi vida), which is meant to rewrite the biography of the Spiritual Leader of the Nation according to the political imperatives of the moment (which include Perón’s highly probable second term and the likely physical absence of his companion). The book is part of a larger set of strategies designed to ensure the active support of the Peronist masses, to encourage their participation and mobilization in defense of their social and political victories. And yet, the defense of these transformations is, in the Peronist epic, the defense of the leader behind them. And so the hegemonic strategies of Evita-ism, accused of being a fanatical cult of personality by a peevish middle class, are all designed to elevate the mother of the descamisados, to present her as both familiar and larger than life. Hence the worn image of Evita as a fairy godmother.

There is, in fact, a bit of magic to this series of operations. Creating hegemony is a process in the tradition of alchemy: activated by a political message, the symbols of social class change hands, value, meaning; they reveal themselves to be unstable, contingent on the accent they pick up in their new context. And so diamonds, those signs of senseless luxury, become, in Lopez’s verse, the proof that she’s arrived… but only recently. Turning the master narrative that at once elevates and vilifies the nouveau riche inside out like the leg of a stocking, Jenny asks, “Ladies, can’t you see I wear these rocks because I’m still just as common as you?”

Evita worked with the same narrative; her love affair with luxury, above and beyond her own personal indulgences, should be taken as a political gesture. It is well known: no one understood the concept of hegemony better than the Peronists. The figure of Evita is rightly associated with concrete victories of the Argentine working class, and with material and symbolic reparations that define the term “social justice.” But these reparations alone do not explain her ascent as an icon, her transformation into a pop heroine, or the intense demonstrations of support she inspired. Again: the alchemy of hegemony is at work here, in pitch-perfect harmony with the economic, social, and technological movements of the time. On the one hand, Evita brings to the region something that has recently been called “the politics of sentiment,” a strategy prevalent in My Reason for Being, which goes to work on the affect of a political collective that fell into rank behind its leader, and which the sobriquet “the mother of the descamisados” brings to the fore. On the other hand, and more in line with Jenny’s glitz, Evita emerges as one of the first South American examples of what Susan Sontag, after Walter Benjamin, has called “politics as spectacle.”

In her indispensable article on what she calls the “fascist aesthetic,” Sontag diagnoses the transformations produced in politics by the emergence of mass culture (in the key of production: capitalism under the Fordist model). These are transformations that Benjamin had already pointed out in several of his best-known essays, but Sontag expands upon them to posit an aesthetics of contemporary political styles. Mass culture demands that politics transform its language, adapting it to the channels of mass communication in which face-to-face interactions disappear and contact is mediated by the latest technologies. Foremost among these, of course, is that of the media, which allows a message generated within the institution and, in the populist tradition, amplified in the plaza, to reach the furthest corners of society. The politician, then, must follow in the footsteps of the actor or the journalist; he has to learn to speak the language of the media, to shine, to rise above the mire and produce his own truth, his narrative, as we’d say today, in tune with the technological conditions of his time.

The finest examples of this sort of political adaptation come, of course, from the fascist bloc. Tied for first place are Hitler and Mussolini, both experts at modifying their message to make it more appealing, and more enthralling, to the listener. Sontag describes meticulously the choreography typical of Germany’s “fascinating fascism,” in which the populace offers itself up to itself as spectacle. At the center of this choreography was a leader who, as if by osmosis, absorbed and redirected the currents of power that circulated among the masses. The leader, for his part, left nothing to chance: it is well known that Hitler’s gestures and hairstyle, along with the tone of his voice and his clothing, were understood and strategized as matters of State.

Evita’s fashion sense, then, is no less than a local take on this historical phenomenon: it is the new world order interpreted with Argentine cheek. It’s worth noting that this does not mean to imply that Evita was a fascist (a label thrown around as though, like a piece of prêt-a-porter, it could be made to fit anyone). Ultimately, fascism and Peronism are more or less contemporary, though divergent, responses to the crisis of representation that comes with mass culture.

And of course no one could occupy this emerging space better than a star on the rise. The channel between the communicating vessels of politics and the world of the spectacle finds, in Evita, its standard. A specimen in transition, a changeable emblem, Evita was an actress before she became a political figure. This biographical detail has been repeated ad nauseum, but its political dimension is not always emphasized. We live in a world in which the media is second nature. Not only politicians, but citizens in general seem ready to take their place in front of the camara at the drop of a hat. It’s worth pointing out that this was not the case in the mid-twentieth century, when media communication still had to be learned, still required training. It is precisely this leap that Evita takes: as a television and radio actress, she learns to fashion herself as an icon, to deck herself out as an object of desire, to present herself as a blank screen on which collective needs and desires can be projected. Politics as spectacle thus implies, first and foremost, the transformation of the leader into a character in a structured narrative that adheres to the codes of the media, a character that speaks the language of telenovelas and tango (Perón was often known to refer to their lyrics), moves like a movie star, poses like a mannequin and dresses like the images of power that circulate in the media.

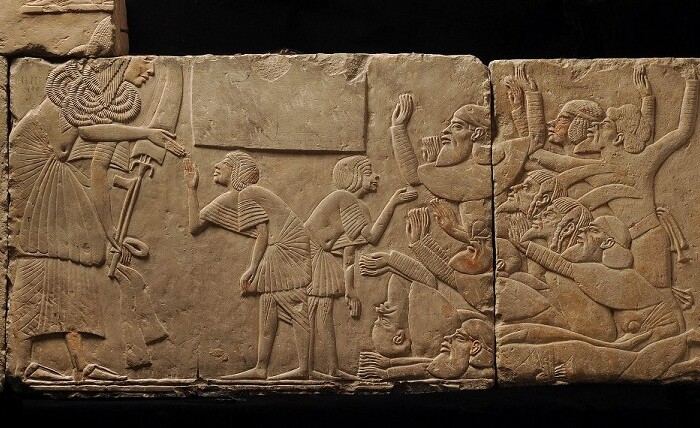

The fact that power is fueled by its own representation has been clear since at least the time of the pyramids in Ancient Egypt. The point here is the way in which this representation changes when new technologies are introduced, and the nature of the political possibilities that they generate. So, then, if the country’s founding fathers were depicted as the secular versions of the European monarchs they claimed to be fighting, Eva Perón finds her handbook of style in Hollywood and in its local translation. Just as we can imagine someone in Cristina Kirchner’s entourage scanning the less daring sections of style.com, it is clear that Evita and those who advised her on her image (a group led by Luis D’Agostino and Asunta Fernández, but which included, particularly in her years as an actress, the fashion guru Paco Jamandreu) were dedicated students of the films of their time. Biographies tend to point to one key moment in this process of translation: when the young Eva Duarte decides to go blonde after seeing Marie Antionette, released by MGM in 1938, and coif herself in the style of its leading lady, Norma Shearer. It is interesting to break down the chain of mediations at work here: a leader in the process of constructing her political authority in a democracy draws inspiration from the mass media’s representation of one of the key figures of absolutism. She is, however—and this cannot be emphasized enough—a queen permeated and shaped by technology. Eva Perón understands that this is the figure of authority most accessible to men and women alike as the era shifts; an image of power that all can identify with and accept. And she sets about turning herself into the local version of this collective dream.

This is the aspiration that Andrew Lloyd Weber captures so magnificently in his rock opera Evita, when he has Eva sing, “So Christian Dior me from my head to my toes/ I need to be dazzling, I want to be Rainbow High… So Lauren Bacall me, anything goes/ To make me fantastic, I have to be Rainbow High,” and so on. The political figure models herself after these accessible, clear images. Piling designs from Henriette, Paula Naletoff, Balenciaga and Dior on top of one another, wearing jewelry commissioned for her through Van Cleef & Arpels by a magnate named Alberto Dodero, Evita hones her skill at enthrallment, creating an image of herself that puts her on par with the most glittering icons of cinema’s Mecca.

Christian Dior’s praise of these efforts is now legendary. Asked about his personal favorites among the members of Europe’s royal families, the brilliant designer declares, “I have only had the pleasure of dressing one queen: Eva Perón.” Dior and Evita starred in their own kind of romance, driven by the aspirations of both. Dior was beginning to introduce the daring details that would define the new look, a return to the princess femininity of the end of the nineteenth century (wide skirts, tiny waists, prominent busts, sloping shoulders), which required a vast amount of fabric and was thus fairly shocking in the context of Europe’s desperate situation after the war. He presents his first collection, a line called Corolle inspired by the silhouettes of flowers, in 1947. Eva Perón meets him in the northern summer of that same year, during the tour that takes her to Spain, Italy, France and Switzerland. From that moment until her death, the House of Dior would keep a dress form with Evita’s exact measurements, on which exclusive designs would be made and then sent to Buenos Aires on Aerolíneas Argentinas planes, where they had their own special compartment (the dresses were shipped upright on mannequins to avoid wrinkles). Dior admired and strove to become an avatar of Charles Worth, who outfitted the Empress Eugénie during the Second Empire; like Worth, Dior finds a political form that combines power and audacity, a mix that critics on the Left have identified as, precisely, the problematic aura of Bonapartism. For her part, Eva not only had to represent, through her dazzling wardrobe (much of which debuted in Europe), the relatively stable position of Argentina on the postwar stage; she also needed, through ermine stoles and silk dresses, to tell the story of her rise into the upper class, waging a symbolic battle along the way with the grand dames of the Argentine aristocracy.

“I want to be beautiful for my little commoners.” The phrase, most likely one of Evita’s responses to criticism of her excesses, suggests that her supporters were part of this logic of splendor. And that Eva was decking herself out primarily for them, as the standard-bearer of the humble masses. In effect, what she represented was not only her own upward trajectory, but rather the newly won well-being of an entire class. It wasn’t she who saw herself as queen, it was the entire Argentine working class, who now enjoyed the benefits of state protection, mass consumption, and vacations in Mar del Plata. “I want them to get used to living like the rich… to feel worthy of the greatest wealth… in the end, everyone has the right to be rich in Argentina… and all over the world. The world has enough wealth in it to make everyone rich.” This is how My Mission in Life formulates the impossible project of Peronism, committed to bending capitalist society to the point it folds in on itself. In this context, Evita’s preening should not be seen as a sign of hypocrisy, or as the most visible manifestation of the contractions that riddled a political program. Ultimately, the Spiritual Leader of the Nation’s affair with fashion is a nod toward a promise that capitalism makes and that Peronism, by sheer willpower, would try to make it keep.

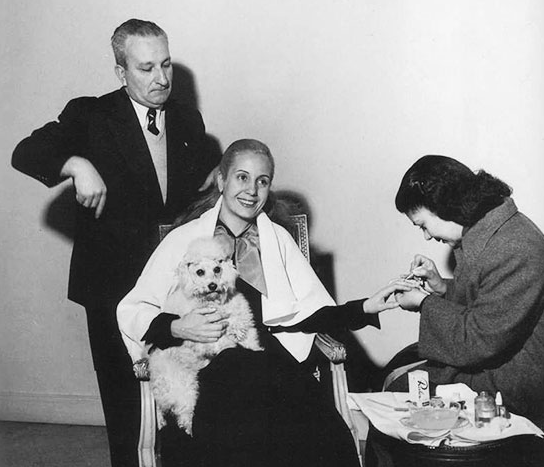

Image: Gisele Freund

[ + bar ]

Kondenswasser

Anja Kampmann

Versuch über das Meer

Es soll um den Horizont gehen den

Farbauftrag der Ferne das helle Knistern

der Flächen von Licht und die Verbreitung

des Lichts wie es... Read More »

Good Enough for Jesus

Russell Scott Valentino

“If English was good enough for Jesus, it’s good enough for me.” —Texas Governor “Ma” Ferguson (apocryphal)

He doesn’t want to say the wrong thing. Who knows what... Read More »

Rowan Ricardo Phillips

TO AN OLD FRIEND IN PARIS

I haven’t seen the ghost of your mother. But I have seen your poems about the ghost Of your mother as she brushes by... Read More »

Passagem Literária da Consolação [são paulo]

Julián Fuks translated by Sarah Bruni

Call it bookstore anxiety disorder. I know I’m not the first to suffer from this affliction, and I won’t be the... Read More »

![Passagem Literária da Consolação [são paulo]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/fuera-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...