An American Poet’s Dream: an interview with David Shook

Interview and introduction by Pola Oloixarac

translated by Heather Cleary

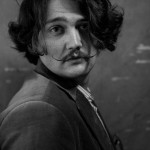

A young professor of literature in Los Angeles collects funding and poems online in order to make his dream a reality: he wants to fly over the territory, dropping poems like bombs. He believes that, in light of the recent history of the United States, cleaving the air with his own drone is the best way to protect poetry: everything else can collapse—NASA can close its doors and employees of the State can fall victim to the shutdown—but military programs remain intact, the drones still carry out their secret missions. By joining with these unmanned vehicles, poetry refuses to capitulate, David muses, twirling his long connoisseur moustache.

The son of preachers from the heart of Texas, David Shook grew up having faith in the spoken word. He studied the lost syntax of languages in danger of extinction like Kiowa and Nahuatl, and translates from Isthmus Zapotec and Zoque, the language of Chiapas. He was not able to raise the money he needed (some ten thousand dollars) on the internet, but that didn’t stop him: the song of the drones has attracted private investors, and he expects to be flying over Los Angeles with his poems within a month.

With his drones, David Shook joins the continent’s long tradition of fighting eagles. Among his inspirations he counts Raúl Zurita, who painted his poems in the air (antecedent prosthesis of Carlos Wieder, Bolaño’s fierce poet-pilot), the CasaGrande collective, which made poems rain down over London, and the Russian Futurist Vasily Kamensky, whom Shook translated from Cyrillic and who was a kind of 1930s Kanye West that saw breasts as earthquakes and life as resurrection. The canon (the poetic canons) range from English to Pashto, Saraiki, Somali and Urdu, by authors like Todd Swift, Sam Hamill, Mandy Kahn, Danielle Moody and Víctor Terán. He hopes to be able to publish the poems of Gaariye, the preeminent Somali bard who sang about nuclear weapons in 1970 and whose recorded voice circulates as contraband; the Sudanese poet Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi, a political exile living in London; along with Said Salah, Caasha Lul Mohamud Yusef, Rifat Abbas and the great Urdu poet Noshi Gillani.

He imagines them crossing the sky like geometrical insects, moving slowly 100 feet above our heads, opening their metal bellies, releasing their precious cargo. The wind is an issue, but publishing poetry is always that: tossing bits of paper into the breeze from too far up, without a care for which way it is blowing.

*

Pola Oloixarac: Obama tried to convince Congress and the G20 to bomb Syria. Whom do you have to convince in order to send out poetry drones?

David Shook: The most pressing people to convince are my potential funders, and I’m still working on that. I’d also like to convince my fellow poets that the Poetry Drone is more than just a gimmick, a look-at-me attention grab. To me it’s about more just the novelty of the poems’ distribution. It’s about the symbolism of transformation: the physical transformation of sword into plowshare. That physicality is crucial to the project—it’s as important as the poems themselves.

What’s behind the superposition of the most widespread literary genre in the USA—that is, war—and poetry, which is the most marginal? What are the implications of turning poetry into a geopolitical experience?

I like the conception of War as a literary genre. It certainly has been core to our national mythmaking. Poetry is a subgenre of speech, of language—it’s our least practical form of communication, and as a citizen of a nation often too impatient or too proud for diplomacy, poetry is a radical alternative to both rhetorical and physical political aggression.

I think it’s important to remember that all poetry is political, and that’s because all language is political. I’m not talking about Democrats versus Republicans, about political parties or principles—I think that kind of stuff typically results in some pretty uninteresting poetry. Language is political because it’s how we relate with other people—and I think that’s the important thing, that we relate with other people, people like and unlike us.

Modern warfare has worked hard to facilitate the dehumanization of our enemies—to eliminate the supposed barbarism of hand-to-hand combat, of seeing our enemies up close, of having to recognize their humanity. To recognize that our enemies are people. But drones are a perfect example of contemporary war’s very real barbarism—from the Greek barbaros, or “foreign.” We’re distancing ourselves from murder; since we’ve justified it in theory we ought not endure the ethical complications of carrying out its physical act. I think this conversation is a worthy topic for our poetry.

Do you think the people who do the bombing will read your poems?

The guys doing the bombing? The teenagers and twenty-somethings joy-sticking Predators from their bunkers in Texas/Florida/Nevada? Probably not. I’d like for them to, of course. I’d love for them to write some poems to be dropped from the drone. How amazing would it be to drop some poems over an army base? I don’t know if I’m ready for Guantanamo, though.

War is so interesting as a horizon; we live inside it, and that’s what I love about your drones: the state of poetry is right there, because war is the reality of the case (“case” in the sense of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus). How do you see this case, this war that is so different from the ones with Iraq and Afganistan?

The United States has been at war my entire adult life, my entire professional life as a poet. It’s difficult for me to know experientially how this case is different from others in the past, but I suspect that our displacement of war has reached new levels. War happens in the background, like an open window on your computer that you’ve buried under a thousand Word documents and Chrome tabs. The average American is not affected by the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, at least not in terms of their daily living situation. This is somewhat less true for those in lower income brackets, and somewhat more true for those in higher brackets. This displacement of war is dehumanizing to those who suffer its effects. War is dehumanizing, period, but we have developed an unprecedentedly effective method of dehumanizing the objects of our supposedly just wars. But here’s the catch: you can’t dehumanize others without dehumanizing yourself. Drones are a physical manifestation of that idea, an emblem of our times. Afghanistan and Iraq are conveniently just beyond the visible horizon. I don’t know a United States at peace. I don’t know that one exists. Maybe that’s true of any political state, inherent to the nature of systems, but as an artist and poet I want to be one of those—and here I borrow from the fantastic South African magazine /Chimurenga/—”who no know go know.”

Have the conditions under which poetry is produced come to resemble the conditions of war?

No. We’ve allocated $91.5 billion to the war in Afghanistan this year, and just under $5 billion to drones, which is a little more than we’ve invested in poetry.

I produce most of mine in bed on a MacBook Air, in my Los Angeles studio, with a tiny chihuahua on my stomach and a fan on my face, or on the bus, on my iPhone. Although I guess that’s increasingly what war looks like to the soldiers on our side of the drones, I don’t think I can compare my own experience of writing poems to the experience of war. I’m immensely privileged, and I think that to claim otherwise is offensive. I do aspire to do more than just document the interior life of the privileged, but I think that the ability to do so is a function of my own privilege. Maybe the conditions under which a Twa woman composes an oral poem, or someone like Raúl Rivero writing poems in prison, or Recaredo Silebo Boturu’s veiled political critique of the police state approach the depraved conditions of war, but not the conditions I write in.

Has poetry gone to war against common modes of existence? Is this a challenge it should take on?

I’m not convinced that common modes of existence are all that common themselves. Common to whom?

Poetry is huge, so I’ll speak only for myself: my poems seek to explore and subvert common modes of language, of communication. That sounds very serious, which it is, but not at the expense of pleasure. Like Biko says, “I write what I like.”

I’m not terribly keen on these types of abstractions—they often lead to very romantic and bourgey notions about writing. It feels dramatic to say that poetry is at war with anything. If it is, it’s doing a pretty shit job of it. Have you seen the soldiers? Most poets can’t swim; their feet blister easily; they’re belligerent, get drunk on the job, and are prone to desertion. That’s our charm, but drones don’t fall for it.

If Hollande ultimately supports Obama’s bid to bomb, will you include poems written in French?

I’d love to include French-language poems! So far I have poems from Arabic, English, Pashto, Somali, and Zapotec, but I’d love to include all the languages I can get. There’s an open call for submissions on my website.

In Elio Petri’s La decima vittima, Ursula Andress is chasing after Marcello Mastroianni, trying to kill him. In the end, they get married and flowers sprout from the gun. If we consider the fact that, instead of bombs, your drones drop poems, doesn’t your project end up aestheticizing war? In the context of the USA’s proposed attack on Syria, is it possible that your project depoliticizes war, and is therefore an inversion of Walter Benjamin’s ideas?

I don’t know that I’ve contributed to an aesthetics of war, though I do appreciate some art that I think has done this, like Mahwish Chishty’s visual reappropriation of drones and Yoshua Okón’s re-contextualization of war exercises (Octopus).

The Poetry Drone is an attempt to aestheticize political engagement, to aestheticize protest. It offers a symbolic alternative to my culture’s promulgation of political and economic domination, of empire. I hope.

At the same time the Poetry Drone is more than just an exercise in aesthetics, in aestheticizing protest, or an experiment in the distribution of poetry. That’s the importance of its physicality. Like Pedro Reyes’ instruments and shovels. Reyes is an inspiration; I would love to meet him.

The PoDro repurposes an actual physical object intended to be used to kill people from the safety and comfort of a military installation some 7,000 miles away.

There are some obvious practical differences—I don’t have the millions it would take to control a drone from that distance, but the model I’m hoping to acquire, which is most often used for aerial photography, can be controlled from over a mile away. The poems that the drone deploys do come from that far away—from Pakistan, Somalia, Afghanistan—and from nearer by.

I’ve joked that if anything, the Poetry Drone might kill children from boredom, but honestly I don’t believe that will be the case. The poems I’ve collected so far are great, and the physical imposition of the drone—a seemingly autonomous machine humming as it hovers in place—will make for an impressive and I hope mildly terrifying display.

I think that Benjamin’s aestheticization of politics applies more broadly to empire, not just to fascist regimes, and thus also describes today’s United States. So sure, the Poetry Drone might politicize aesthetics, but I’m hesitant to say that it does so in the heroic and antidotal mode that Benjamin envisioned. I do think that there is an inherent relationship between aesthetics and politics, but I’m no scholar and I haven’t worked out its exact nature—maybe you, Pola, could help me come up with some wild theories?

* *

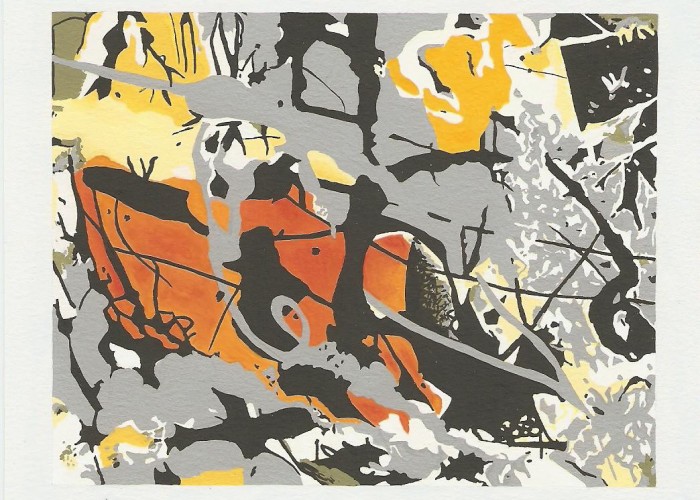

Artwork: Rosario Zorraquin, “Guerra” (2013).

* *

David Shook grew up in Mexico City before studying endangered languages in Oklahoma and poetry at Oxford. His collection of poems Our Obsidian Tongues, longlisted for the 2013 Dylan Thomas Prize, is available from Eyewear Publishing. He served as Translator in Residence at the Poetry Parnassus in London, where he premiered his covertly filmed documentary Kilometer Zero, featuring Equatorial Guinean poet Marcelo Ensema Nsang. His translations include Mario Bellatin’s Shiki Nagaoka, Oswald de Andrade’s Cannibal Manifesto, and Roberto Bolaño’s manifesto Leave Everything, Again. He lives in Los Angeles, where he edits molossus and Phoneme Media. (Photo: Crispin Hughes)

David Shook grew up in Mexico City before studying endangered languages in Oklahoma and poetry at Oxford. His collection of poems Our Obsidian Tongues, longlisted for the 2013 Dylan Thomas Prize, is available from Eyewear Publishing. He served as Translator in Residence at the Poetry Parnassus in London, where he premiered his covertly filmed documentary Kilometer Zero, featuring Equatorial Guinean poet Marcelo Ensema Nsang. His translations include Mario Bellatin’s Shiki Nagaoka, Oswald de Andrade’s Cannibal Manifesto, and Roberto Bolaño’s manifesto Leave Everything, Again. He lives in Los Angeles, where he edits molossus and Phoneme Media. (Photo: Crispin Hughes)

[ + bar ]

The Tall Trees: A Juno Novelette

Paul Scheerbart translated by Joel Morris

The tall trees groped more and more intensely in the air with their long branch arms and could not... Read More »

Hegira

Adam Morris

Slakers shambled along the coasts, the brine in the breeze searing nostrils, lashing cheekbones and the edges of eyelids, whittling parts of faces to... Read More »

The Ceremony

Inés Marcó translated by Alex Niemi

CAST

Pope Layman Guard of the Brotherhood Brothers of the Circle

The characters meet at the entrance of a large urinal. The Pope is... Read More »

Marina Mariasch

translated by Jennifer Croft

HOW WILL TERROR TAKE ROOT IN THE FUTURE?

We jump right in, head first. The beginning is incredible. Halfway through is incredible. You quit smoking. We do the... Read More »

sending...

sending...