Lions

Iosi Havilio

translated by Andrea Rosenberg

And in the middle of the day came the night . . . Down the hill, all made of shadows, the Protagonist strides along the paving stones, midway between the cordon and the buildings, left, right, left. The past approaches and he gives in to it: all those moments of afternoon and freedom festering in the open air, consuming down the block, amid zombies and doormen. Nearer by, businesses, those tender galaxies of cheap hankerings, of good rates, of infinite love for the craft, record shops, discount stores, lottery ticket sellers, lingerie boutiques, all crammed together, embracing him to recall those aimless hours . . . unhurried, unhurried, ly: the syndicalist girlfriend with a satellite phone, the boy with the acid feet, the ardent interlocking of tall glasses wet with Criadores whisky, the invasion of African fleas, the blow jobs in mirrors, the slashes on cheeks, and the one-night stand. And bam. Bam. Footsteps that left marks on the parquet like hydrochloric splashes, that gave off smoke, never seen before, ever. Godzilla feet toughened by the neighborhood. The same day a well-aimed chunk of ice split open the skull of a bald and probably deceptive workman waiting for the bus to Flores. The same day the Girl Saint with the burned face showed him her little breasts while dressed as a ballerina before tossing the wartime newspapers into the void, thinking them too old. Some were saved, paradoxically, a selection of the goriest front pages.

A new stoplight, three-sided, confusing even to the most competent, now has him pausing perplexed on the corner in question. The green is taking forever and the Protagonist instinctively looks up to see an enormous airplane land on the avenue, a plane, a bird, a paper condor, a fake fighter jet, and others trailing in its wake, forming a V that passes over the tall wrought-iron fence of the church and alights almost delicately, like dancers, before the pointed-arch gate. The Protagonist doesn’t need to look up; he knows the person throwing them is Himself, four stories up, twenty-two years back, in an endless succession, in search of perfection. It is his own hand, imploring, that pokes out between the railing and the abyss, fishing for applause, but how did he do it, he wonders: How did he manage to stay crouched there this whole time, who took care of feeding him, how many new owners and tenants have passed through since then, through the concentration, ever since the storage trunk, the Russian yuans, the bunk bed, the lighted display cases, and the pocket illustrated raskooooolllnikov… He now, He then, had calculated badly, had let himself get swept up in the round number, it was many more years, and he’s not sure how it has ended up coming back to delight him, in top form, with such skill, his best weapons now an expert wrist, superpowered, bam, bam, bam, thirty planes a second, a range of throwing styles, gauging altitude, force, and direction, knots and atmospheric pressure, taking into account the positioning of the stars, the power of the winds: Had he chosen to specialize, or had he had no other option? The Protagonist on high no longer questioned it, he had mislaid talking up there, nobody ever scolded him for his behavior or asked about the newspapers that were gradually disappearing—the tenants were swept up in the idea of a natural recycling process, others had problems in the bosom of the family, with love, with drugs, with money, at work, too many worries to think about yesterday’s news. Meanwhile . . . He remained imperturbable, crouched behind the large planter, working on his holds, out in the chill of that parched land, but he didn’t live so badly there in secrecy, no cyanide pill clenched between his teeth, and it’s no big deal. It’s A Consecration like so many others, an interruption—the Protagonist has nothing to feel guilty about, taking the craft to the very pinnacle of practice, isolation, a bit of mystery, to enjoy deeply and calibrate the organic scales in daylight, so that the nighttime illuminates the ailerons and the engines and the cabin crew. And now that his mind is wandering back to the walkway outside the church, the atrium has turned into a runway covered with paper machines that do not touch or overlap, so much alike in the apparent chaos.

*

The Protagonist had risked moving to the middle of the avenue to admire his work from the median. And today, more than ever before, his Young Self up above was going to great pains to ingratiate himself. It was then that he saw how an infinite number of airplanes of different sizes, colors, and weights sketched out in the air, as if it were a work of art, Three Lions (two awake, one dozing).

But not just any Three Lions, chosen at random in the jungle: Three Lions that make sense, modeling their manes to make themselves known, Three Lions that named him gutturally, amid roars they named Him, Three Lions that greet him with smiles, though the sleepy one does so through gritted teeth; his mouth falls open too late, no time to be surprised, these Three Lions are beyond prowess, those manes exist, those gleaming fangs interrogate him, they are all too familiar with the Catalogue of His Virtues, Defects, Vices, Calluses, Weekly Horrors, they know Him by heart, have seen Him cry, masturbate, look up at the stars a massive fool, tear up at songs as the year draws to an end, hug strangers on the beach, party hard, say stupid things; they know he’s one-eyed, a poet, affectionate, and dead, Three persistent Lions, which he carries within like the fingers of the three moments he’s lived so far, his entire hermeneutics—Nothingness, Almost Nothingness, and Great Nothingness again—they saw him tan his wounds in the dry plaza, weep along the corridors of a hospital on strike, insolently stand firm before A Composer and not come out victorious, they know that one of those snooty-rich-girl dogs pissed on his shoulder while he was sunbathing and he couldn’t assert himself, played the game of nature, they were there the evening he hurled a cat against a wall, unable to endure the caterwauling of his conscience any longer, they swept up its remains with a broom and dustpan the night he said: This is my weakness . . . ! but they don’t judge or scorn him, they know how to forgive. How many times had they seen him happy? Truly happy, replete, satisfied with everything. Seven? Eleven? Thirty-six? The figures vary according to the criteria. The image begins to move. These Three Lions that he’s created now show their half-open maws, their eyes sweet, impish, terribly knowing, as if saying: Trains don’t go by carrying the same nectar twice . . . The changes pick up speed and things begin to disintegrate, manes for snouts, snouts for claws, claws for eyes—the oracles vanish without warning of a danger the Protagonist does not understand or perceive. In an instant, the show becomes too showy: immense emptiness, pure skill, virtuosity: the sadness of the year; the clamor so as not to end up denouncing what he had so often mocked on the way out of a theater, at the entrance to some concert under the bridge, listening to altered standards, that little speech he’d developed and that he knows is old but that fits him effortlessly, that pap for dimwits prepared each day by those devoted to functions and strategies. . . the result: a blow thunderous like a yeti’s slap; but after the fervor and the inflation had passed, after the grimace of irony, there was no other option; and so the Protagonist, King of the Dilettantes, shuffles across the avenue and lets some of his own inventions trail in the ether behind him as if it were no big deal: An Indian woman giving birth at the edge of a canyon; A pedophile priest killing himself on the Internet; The critical mass leaving at dawn.

The Protagonist thought: That’s the way the past is—it strives to look like shadows of brilliance, strokes of paper genius that drift away on the breeze. He took one last look; a coven had taken over everything. And he’s already starting to forget, the way you forget juggling as soon as it’s over, and he heads to the front in his daytime night, and he’d go far, except that resentment produces imponderables when the Self appears. The attack begins so subtly . . . Who would have thought a pawn would head up the onslaught? A twinge in the back of his neck pricks him, yes, but it might be nothing. A sting lost in the aura. But straight away another one. And another one. Ow, and one more. Ow ow ow. They’re backstabbing the nape of his neck. He turns to look and a thousand planes are coming at him, a brutal offensive with him as its only target, perfectly aimed as there’s no one else on the runway. He already knows, no need to check: the hand firing on him is always the same one, his hand, larger and hairier, clenched and angry, reflecting his art of vengeance, all those years sunk in that foul activity, pigeon of doom, and now this footbath indifference, but there’s no time for dialogue or considerations, those killer birds stop being made of paper, shift, grow claws, wings, predatory beaks . . . The Protagonist has no choice but to flee through a bottleneck, frantically waving his right arm as if splitting the air, the fingers of his other hand shielding the gashes on his bloody neck. And he’s bleeding, yes he’s bleeding. He’s not hallucinating—it’s what’s actually happening.

* * *

“Lions” is an excerpt of Havilio’s upcoming nouvelle, La Serenidad (Entropía, 2014)

[ + bar ]

Condensed Water

Anja Kampmann

About the Sea

The horizon is the concern here the

distance applying color the bright crackling

of surfaces of light and the spreading

of the light as it surges the... Read More »

Maxine Chernoff

For every appetite there is a world. —Bachelard

You starred in the movie with Maud Gonne and Socrates and Juliet and a flock of sparrows... Read More »

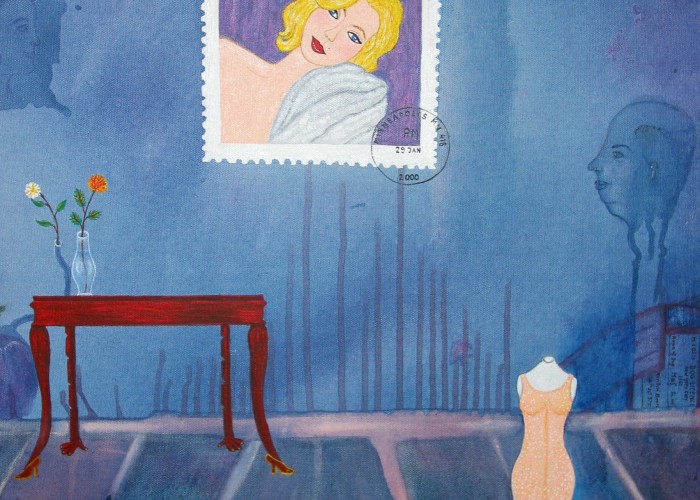

Marilyn Monroe, my mother

Neda Miranda Blažević-Kreitzman translated by Ellen Elias-Bursac

Many people wrestle with discomfort and fear when they travel by air. Dino Lučić and Veljko Linić were... Read More »

Passages: My Art as an Everything

Natalia Brizuela on Nuno Ramos translated by Andrea Rosenberg

“No sé.” “I don’t know.” That’s the response Tintin and Captain Haddock get from the inhabitants of the Andean country—vaguely... Read More »

sending...

sending...