The Internet as Novel

On Carlos Labbé’s Piezas secretas contra el mundo (Periférica 2014)

Samuel Rutter

A recent interview in El País identified Carlos Labbé (Santiago de Chile, 1977) as a writer at the forefront of a generation returning to the complex relationship between avant-garde literature and political engagement. In keeping with this characterization, Labbé’s latest novel, Piezas secretas contra el mundo, published in March by Editorial Periférica is an ambitious declaration of principles for a new understanding of the novel in the twenty-first century.

Those familiar with Labbé’s growing and challenging body of work, beginning with the hypertext novel Pentagonal, will recognise in this latest novel some of the tropes the author continues to address. There is a particularly textual nature to the worlds Labbé creates, where the acts of reading and writing form an essential part of the fabric of reality in which his protagonists exist. The increasingly political edge to the author’s prose manifests itself in this novel through its ecological themes, which have come to include the status of indigenous cultures in Chile. Labbé’s prose, full of surprisingly juxtaposed registers and genres, matches its form to its content and embroils the reader in the fusion of these competing elements in order to construct a meaningful, overarching narrative.

Presented in the form of a “choose your own adventure” novel, it is the reader and not the author who actively constructs the narrative of Piezas secretas. There are obvious affinities here with Cortázar’s Rayuela, which celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year, but while Cortázar gave the reader a roadmap and left the ludic structure of his novel outside the narrative, Labbé’s work begins with a gnomic prologue that immediately involves the reader and layers the metafictional instructions inside the story, often providing the reader with several options for movement within its pages. As such, the experience of reading Piezas secretas is disruptive and alluring at the same time – as the reader constantly moves back and forth through the pages, it is impossible to know exactly how deep into the narrative one is at any given point. Considering the mechanics of Labbé’s prose is like pulling the case off a desktop computer and watching it tick—there is a constant hum of activity, with bulbs blinking in the darkness and a mass of plugs and wires leading in all directions, and just like the virtual memory of a computer, Labbé manages to give his narrative more scope than appears possible in a conventional 220 page novel.

In Piezas secretas, the reader is confronted by a seemingly endless array of plotlines. To name but a few, there is a report compiled by the pluriform author 1.323.326, a videogame written by a spurned lover, and the decay of thousands of salmon from the disastrous artificial farms in the south of Chile. There are references to Gabriela Mistral’s Poema de Chile, the literary preferences of Alonso de Quijano, Gregor Samsa, and Emma Bovary, as well as a thwarted claim for colonial compensation from the King of Spain by a hypothetical author named Carlos Labbé, who may or may not live in the state of New Jersey. The geographical setting of the novel is just as diverse. While much of the action revolves around the aptly named town of Albur in Chile—which the reader can choose to destroy in a literary inferno, much like Onetti’s Santa María—, downtown Santiago and the library of a university in Bergen, Norway could also play a prominent role, depending on the volition of the reader.

The achievement of Labbé’s novel, for all its peculiarities, is that it marries form and content in such a manner as to sustain itself as a narrative, while opening a dialogue about what the novel might come to mean in the digital world: if his earlier work Pentagonal is a narrative published on the Internet, this feels more like the Internet itself as a novel. Piezas secretas is plugged in to a hyperlinked reality where there is a symbiotic relationship between reader and writer, consumer and producer. Exactly where the intersection between literature, politics and ecology in the new millennium lies is a question at the heart of this novel whose structure hints at a possible answer—in many different places at once, just a few clicks away.

* *

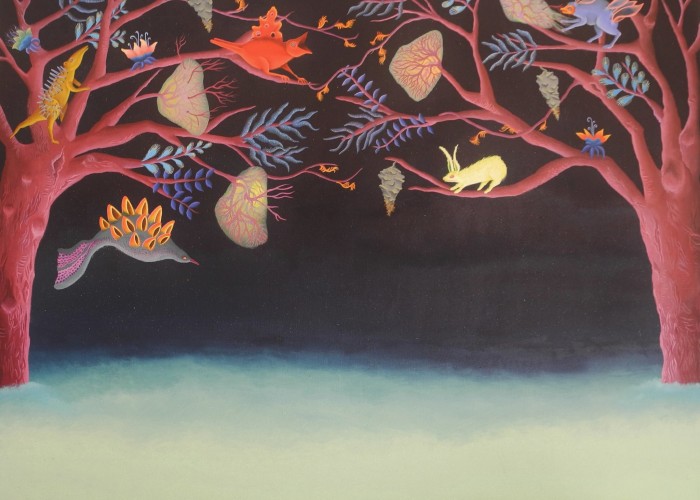

Image: “Blinded” by Love Lundell. Curated by Marisa Espínola of Espacio en Blanco. (More)

[ + bar ]

The Reversal Spell

David Leavitt

The day that Paris was declared an Open City, I went to say goodbye to the Baron. He was one of my oldest friends.... Read More »

Trees at Night

Ramiro Sanchiz Translated by Audrey Hall

On the outskirts of Punta de Piedra, there is a bar a good distance beyond the last line of houses. From the untidy... Read More »

The images featured in BAR(2) were selected by Marisa Espínola and appear courtesy of:

Espacio en Blanco www.espacioenblancocultural.org

Espacio en Blanco began in Buenos Aires in 2009, when writer Francisco Moulia and... Read More »

O único final feliz para uma história de amor é um acidente

Não posso vê‐la esta noite

Tenho que desistir

Então vou comer fugu

Yosa Buson (1716‐83)

1.

Antes do sr. Atsuo Okuda abrir a caixa, tudo estava... Read More »

sending...

sending...