Argentina and Uruguay (excerpt)

Lucas Mertehikian

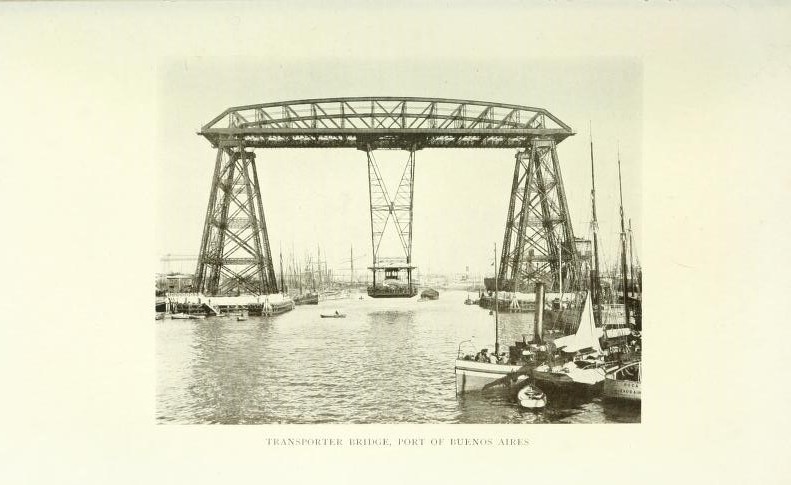

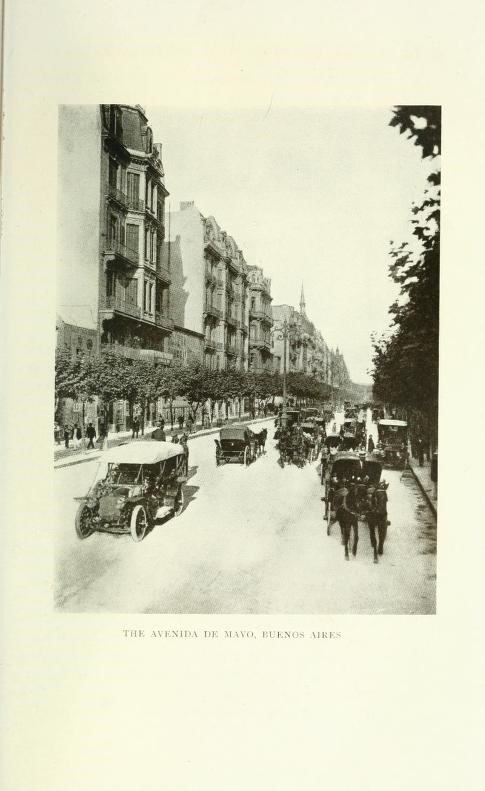

We don’t know much about Gordon Ross. We don’t know how long he lived in Buenos Aires nor where exactly he had come from. The first pages of his book Argentina and Uruguay only tell us that he served as an official translator for the Fourth Congress of the American Republics, held in 1910, and as a financial editor for The Standard, a journal addressed to the English-speaking community of Buenos Aires, first published in May of 1861 as The Weekly Standard and which kept coming out, with slightly different titles, until 1959. The editors had made their initial statement in the first issue of 1861: “The Weekly Standard in unfurled to the four winds of heaven, not as the emblem of a party or the watchword of rivalry, but as the bond of fellowship between the various members of the Anglo-Celtic race.” Argentina still hadn’t received the overwhelming wave of immigration that it would later receive at the turn of the century, but The Standard was already an early witness of the process that would shape the country’s social physiognomy forever.

This is precisely of one Gordon Ross’ main concerns. First published in New York in 1916, and later republished in London 1917, Argentina and Uruguay was actually written in the midst of that deep process of social transformation and, therefore, poses a question which is impossible to answer: what will become of the future Argentine? Perhaps because of his work as a financial journalist, Ross can’t help to relate the Argentine’s features with the business opportunities that flourished in the country at the beginning of the 20th century. However, he notices the same basic features that John Foster Fraser had observed before him and Katherine Dreier would highlight soon after: a widespread lack of organization, a wild and rather irrepressible nature, and the tarnished role of women in local society. Also, like Foster Fraser and Dreier, he outlines a genealogy for the Argentine people that goes back to the Spanish conquerors and their Oriental heritage. Unable to predict what was about to happen, in this first excerpt Gordon Ross focuses on a different question, hoping that an accurate answer, combined with his knowledge of the past, would allow him to glimpse that obscure future: What are Argentines like today?

Racial Elements and Social Conditions

Gordon Ross

What will be the result some generations hence of the enormous influx of immigration from all parts of Europe to Argentina and in, as yet, a much less degree to Uruguay? What manner of man will the Argentine of the future be when he has completed his development as a national type? This is a question often asked, but as to which only the most shadowy answer can yet be given. The elements which are going to his formation are so many and the qualities of those elements so difficult to reckon in regard to their respectively possible likelihood of survival in the settled type. The most that can be done here is to enumerate the chief of such elements in their approximate quantitative values.

The true Argentine of the past is the descendant of the Spanish conquerors with usually some admixture of native Indian blood derived from a remote ancestress, while another less remote has perhaps given him a tinge of black blood in remembrance of the days when African slave labour tended his great-grandfather’s sugar canes and maize.

But Spanish blood is predominant and Spanish qualities distinguish most of the Argentine, and all of the Uruguayan, leading families of to-day. Ceremoniously courteous to a fault—the fault of deeming it rude ever to refuse a favour asked; regarding it as a strange lack of savoir vivre on the part of the suppliant should the latter not understand the granting as a mere polite formality, in no way to be taken as a serious engagement.

An Argentine will ask a favour of another as a mere hint that he would be very glad if the latter granted it; a stranger ignorant of Argentine manners and ways might ask it really expecting to receive a substantial response to his request. Both would be met with a charming if vague assertion that nothing would give the person asked greater pleasure than to do anything the asker desired. Each might attain his object or not, as other considerations dictated; but whereas the demand would be credited to the former as finesse, contempt for boorishness would be the lot of the latter did he present himself expectant of the immediate fulfilment of the promise. Almost as well might he turn up unexpectedly to lunch at the home of an Argentine who on first receiving him had said with a graciously comprehensive wave of his hand, “This house is yours.”

As a matter of fact an Argentine’s home is a very difficult castle for a stranger to enter.

This probably for two chief reasons. For the first of these we must trace racial elements back to the Moorish civilization of Spain and the jealous seclusion of women from all male eyes but those of close relations. The second is a general lack of orderliness (also an Oriental characteristic) usually pre vailing in even the richest Argentine households ; which makes it inconvenient to receive except on special and specially prepared occasions.

We must follow up the Arab-Semitic blood brought in the veins of the Spaniard to the new world through mingling with Native Indian and Negro blood before we come to the heroes who fought for and won independence from Spanish rule now over a century ago. Since then what intermarryings, mostly with natives of Italy but also with British, French, German, Scandinavian and Belgian men and women.

Guthries, Dumas, Murphys, Schneidewinds, Christophersens, De Bruyns, Bunges, not to mention bearers of the historic patronymics of Brown and O’Higgins, are now among the landed aristocracy of Argentina; though, still, the crème de la crème consists of the descendants of the Spanish families of Colonial days. Among the middle and lower classes, especially in the towns, the Italianate element is now overwhelming; though recently again Spanish immigration has begun to exceed Italian. All this goes to make a strange racial mixture; of which the first generation born on Argentine soil knows little about and cares nothing for the language of its parents, but grows up with a pride, comical to the detached observer, in the glorious Wars of Independence (fought at a period when its own ancestry were, as likely as not, peasants in one or another comer of Europe, and wholly ignorant of the fact of the existence of the River Plate) and patriotically devoted to the blue and white Banner and National Anthem (an Italian composition, by the by) of the land of their parents’ adoption.

Everyone born on Argentine or Uruguayan soil is Argentine or Uruguayan of his own very decided will as well as legally; furiously so with the exclusive fervour of the convert. He cannot or will not speak English, French, German, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish or Flemish as the case may be ; nothing but Spanish, River Plate Spanish, that is to say, is worthy of his tongue, and he has a truly Galician contempt for the lisping Spanish of Castile.

Contrarily to a generally accepted but quite superficial view, an Uruguayan differs from an Argentine almost if not quite as much as a Portuguese does from a Spaniard; the reason being that the early immigration to the two countries was drawn from different parts of Spain. The first settlement of what is now Uruguay was chiefly drawn from the Canary Islands and the Basque Provinces; the latter origin being easily perceptible from a glance at any list of the names of prominent Uruguayans, past or present. To this fact of early settlement and because Uruguay has, until quite recently, offered much less attraction to the stream of European Emigration which flowed past Montevideo to Buenos Aires, is due the possession of the high degree of many sterling qualities which distinguishes Uruguayans from their cousins of the other shore of the River Plate. These qualities have sustained the National and individual financial credit of Uruguay throughout all troubles and political vicissitudes. She as a Nation and her individual traders have always paid loo cents gold to each dollar and her commercial community has successfully negatived any attempt on the part of her Governments to depart from the strictly gold basis of her monetary system. The Uruguayan dollar is worth slightly more than that of the United States. This significant fact is due to the uncontaminated preservation of racial qualities derived through the old Colonists from the Northern parts of Spain; especially from the Basques, than whom no honester, nor perhaps more obstinate, people exist.

[…]

In passing from comparison to particular analysis one is at once confronted with the difficult question, “What is an Argentine?”

[…]

The true Argentine, be he patrician, estanciero or gaucho peon is never boorish even when he’ seeks to pick a quarrel with studied insult; and if his humour and language would, at times, severely shock European ears polite, he is studiously careful to keep that sort of talk for the intimacy of his own household and associates. If you are admitted to that intimacy, well, so much the worse for you, if you are of a prudish disposition, but you can console yourself that your privilege is a very special and rare one; bestowed on you by virtue of some exceptionally sympathetic quality with which your host’s kindly imagination has endowed you. He is a kindly, charitable man, the real Argentine: an odd mixture of infantile vanity and strong common sense, hospitable to any one arriving at his house through force of circumstance or if he can find a reasonable excuse to himself for breaking through the rule of almost hareem-like privacy of his home and intimate family affairs. Courteous himself, he expects courtesy, and will not brook clumsiness of speech or manner. Leisurely in his ways, he will not be hustled over any business. Try to hurry him, and he not only resents your lack of good manners but also suspects that you are endeavouring to lead him into some kind of sharp-dealing trap. Anyway, he not only will not budge an inch from his own deliberate attitude but most probably will oppose the inertia of a closed front door to all your further endeavours to approach him. This Argentine characteristic is a rock on which many a Yankee hustler has seen his best thought out propositions founder.

In any business or other intercourse with a true Argentine you must not expect him to keep verbally made appointments nor to apologize subsequently for not having done so. Usually you need not trouble to keep them yourself. What ever you have in hand with him will prosper better and progress just as, or even more, quickly if you are content to take the matter up where you left it at your last interview, the next time you happen to meet him by chance at any at all convenient place or time. Do not talk him to death about it, he is very quick at understanding your wishes and proposed plans from the merest hint. If not, he will ask you very plain questions.

But he must conduct the negotiations, he must clothe your ideas until they bear a respectable appearance of being of his own originating. That is his vanity; but only then may you venture to strip them of certain new features which on close examination will be seen to be more favourable to his interests than your own.

During the changes which your propositions will inevitably undergo in the course of negotiations, he may, if you are not careful, get the better of you in the deal. That also is his vanity; a vanity to guard against without ever committing the solecism of a too bluntly apparent discovery of his aim. If he finds you always politely firm as a gentleman should be, you will have gained his friendship and respect—often valuable assets even if your original business should not go through.

In a word, in Argentina, as elsewhere, one must respect the native customs and conventionalities unless one wishes to encounter opposition. And the vis inertia of the opposition which an Argentine can and does offer to persons and ideas with which he is out of sympathy is invincible.

Such persons or schemes will be remitted by him to a “Mañana” which never comes. That is the true inward meaning in Argentina of mañana; a polite excuse for temporarily or definitely postponing matters which have not made a favourable impression. It is not, as is so often thought, a mere lazy pretext for not doing to-day anything that possibly can be put off till tomorrow.

[…]

Argentine women? This is a subject on which one is not only tempted but almost forced to confine oneself to the usual platitudes concerning beauty of the Spanish type: large-eyed and opulent and at its apogee during the decade between 15 and 25 years of age. It is seldom that an Argentine woman of any class troubles her head with business matters; still less with theories concerning the rights of her sex. She is usually content to do her most apparent duty in the sphere to which it has pleased God to call her.

She manages her household in a quasi-Oriental haphazard way; if of the wealthier classes does little but order that household in such ways as may correspond to her momentary caprice, if of the poorer, naturally, she does the work herself, but in the same capricious fashion.

Saturday is the great day for domestic cleaning up throughout all classes, Sunday a feast day whereon little work is done.

Apart from these general fixtures, household duties may be said never to be begun and never finished. In all houses one may see the servants or the housewife, as the case may be, besom in one hand and mate in the other at any time of day. What is not done to-day is finished to-morrow, that is all; and what can one do more?

To newly arrived Europeans these methods give an idea of continual discomfort, but the sooner such Europeans become accustomed to the ways of the country in this as in other matters the better for their own peace of mind. Of one thing they may be assured from the commencement of their stay on the River Plate, viz. that it is not they who will change those ways by an iota, and that therefore they may as well abandon all notions of what they would consider as reform of good grace to begin with instead of at the end of a more or less lengthy nerve-racking struggle.

The servant difficulty is particularly difficult in these sunny lands where no one need, and very few do, know what it is to suffer the real pinch of want or of hardship other than such as custom sanctions. The European lady who worries her servants with, to them, new ideas of how her household should be conducted will simply cause them to quit her employ with wonderful unanimity and celerity.

They won’t stop, that is all. She may give them sleeping or other accommodation which they may never before have enjoyed nor probably even dreamed of. These attentions strike no sympathetic chord if they be accompanied by what the native Argentine considers silly pettiness of interference with the way in which he or she is accustomed to do his or her work. Any Argentine servant would sooner sleep, as many do, on a mattress thrown down at night in any passage way in the house of a native Argentine family and suffer the alternate friendly familiarity and impassioned scolding of a mistress whose ways they understand and who leaves them to theirs, than occupy the nicest possible servant’s bedroom in a more strictly ordered establishment. The true and main lesson of all which is that the Argentine, to whatever social class he or she may belong, is a child of nature to whom disciplinary fetters of any kind are unbearable and to the freer nature of whom the monotony of much of the punctual regularity which Europeans are apt to consider a necessary factor of real comfort is impossibly burdensome.

* *

Gordon Ross. Argentina and Uruguay. New York, The Macmillan Company, 1916.

[ + bar ]

I’ve Lost Everything I Loved (excerpt)

from J’ai perdu tout ce que j’aimais by Sacha Sperling translated by Addie Leak

I had decided that my name would be Sacha Sperling and... Read More »

Edipo [buenos aires]

Milton Läufer translated by Heather Cleary

It’s true: Edipo is an ugly bookstore. And yet, though this may seem like a contradiction, its most notable... Read More »

Dubitation (a selection)

Martín Gambarotta Translated by Alexis Almeida

Here, the water is different, the artichoke

leaves are different, everything is

in essence, different,

but he who takes the bottle from the refrigerator

and... Read More »

After Kenneth Goldsmith: an interview

Michael Romano and Kenneth Goldsmith

I.

I have a bunch of questions but they’re still pretty disorganized in my mind.

So let’s just shoot.... Read More »

![Edipo [buenos aires]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/Screen-Shot-2013-04-20-at-11.16.56-PM-700x500.png)

sending...

sending...