The World Wide Widener

Patricia Marechal

The story of Widener Library starts with a tragedy. Widener is not only a place of study and one of the largest reservoirs of books and periodicals in the world, it’s also a memorial. The act of devotion of a mother who lost her son in the Titanic shipwreck. A real Trauerarbeit. Harry Elkins Widener, Harvard class of 1907, loved and collected books. Upon his death, his mother decided to donate his enviable collection, plus a considerable amount of money, to build what today is Harvard’s most impressive library. Widener is both the geographical and symbolic center of Harvard University, and the building that every tourist wants to see. One cannot climb the thirty steps of Widener’s broad front stairs without having to dodge a tourist guide immersed in the act of narrating the tragedy of the Widener family. It’s hard to blame the overeager undergraduates that officiate as amateur guides for their excitement. How to avoid the temptation of mentioning the story of the library’s birth? It’s simply too good to be true. An aura of personal heroism, or madness, surrounds the building: legend has it that Harry Widener was about to step into a lifeboat when he remembered that he’d left behind a rare copy of Bacon’s Essais that he’d purchased in his travels around the Old Continent. So he went back to recover it, and in that attempt he “lost the boat” and his life. In other words, books killed Harry.

As impressive as the Titanic itself, Widener emerges from the heart of the so-called New Yard, an area adjacent to the old university campus where the first buildings of Harvard College, which date back to 1636, are located. Is Widener Library the most emblematic building of the New England red-brick campus? Perhaps on its best days. The building that stood out to my eyes when I first arrived was Memorial Church, right opposite Widener Library. “Universities here have churches,” I worried. My worries only increased when I came to realize that, while Memorial Church has its doors open to all, accessing Widener Library is not so easy. In fact, it’s almost as difficult to “get in” as it is for a camel to go through the eye of a needle. To access Widener one has to pass a guarded gate wielding a Harvard ID that few possess. Harvard students like to contrast the restrictive access of their library with the democratic “all-welcome” policy of Harvard’s Cambridge cousin, and at times rival, MIT. But this is merely the tip of the iceberg that serves as illustration and summarizes the Harvardian lifestyle.

If you are one of the chosen few, once you get in Widener its imperial style salutes you. Immediately you find yourself in a panoptic hall where you have to choose your own adventure: periodicals at your right, stacks at your left, and majestic marble stairs at the front, leading to a special room with a Gutenberg bible and copies of the first folio of Shakespeare. Like the Titanic, Widener has several levels. Above the ground, the splendor and poshness of the reading rooms and exhibition halls dominate. Two First World War murals by John Singer Sargent stand at the sides of the main exhibition room. Incised below one is the motto “Happy those who with a glowing faith in one embrace clasped Death and Victory.” Below the other, “They crossed the sea crusaders keen to help. The nations battling in a righteous cause.” In both an American eagle spreads its wings. As a scholar, the link between victory and death seems a ghastly prospect. Even more discouraging is the strong suspicion that one’s dissertation is far from being worthy of the label “righteous cause.” All in all, the eagle speaks to me more of Prometheus’ punishment than of glory.

The next level is below the ground. Unbeknownst to those who see it from the outside, there is a subterranean Widener: a labyrinth of tunnels where most of the collection of books is stored. To look for a volume, scholars have to descend deep down and cross narrow paths illuminated by dim artificial lights, impregnated by the rancid smell of moss and enclosed spaces, and transversed by rusty leaking pipes. The infra-world of Widener’s arteries hosts the stacks of books, stored in pliable metallic book-shelves that, to gain space, fold and unfold like an accordion. At the pressing of a button, hundreds of dusty books are revealed and become illuminated by tenuous lights hanging from the roof. I often feel as if I were in some 1940’s archive of a noir film secret police. When the shelves display their fruits, one rejoices by the finding of an eighteenth century copy of Anacreon, or a bilingual edition of Petrarch. Once the coveted issue has been found, one is ready to emerge, treasure in hand, to the luminous, sunlit exuberance of the reading-room paradise. The return from the nerdy Hades comforts and cures momentary claustrophobia: students are once again able to breath clean aristocratic air.

But the reading rooms are not always a recovered paradise for the regulars of Widener Library. For most of its inhabitants, the feeling is of purgatory. Doctoral students populate the large halls, which are lit by lamps with cliché darkened green or golden glass shades. One can smell the anxiety of “dissertating.” Open-ended writings that never seem satisfactory, piles of reserved books that always multiply like the bread and fish, but often offer no nourishment, frantic hands scanning hundreds of pages in vain. Looks of support between students mix with gazes of envy each time someone seems “in the zone.” The scholars form departmental clusters, taking over specific areas of reading rooms. In the Phillips Reading Room, the Romance Language Department gathers. Every now and then, someone asks their colleagues in a whisper if they want to take a break for coffee—not for cigarettes anymore, as the university has recently passed a tobacco ban.

It takes a little while to realize that there is a third floor (maybe paradise, finally) where private libraries are located. A Russian nesting library. The smaller libraries inside Widener belong to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, for short FAS, and are even more secure and demand yet more special permission to gain access. Not any Harvard ID can open their doors. One can only wonder what bibliophile dreams lay inside; their windows occluded by opaque 1950s khaki curtains. Walking through the narrow corridors with high ceilings where the FAS Departmental Libraries are located is like a trip to Widener’s past: the Celtic Seminar Library, the History of Science Library, the Paleography Library, the Sanskrit Library are all flanked by old library index card cabinets. The first time I walked down those corridors, it was impossible not to notice, smirk, and shiver when I glanced at some of the yellow labels indicating the first and last cards archived in each cabinet: “Moscow ~ North,” “Fisheries ~ France,” “Economic ~ English,” “Warsaw ~ World,” “Bhagavadgita ~ Businesswomen,” “Argentina ~ Bhagavadgita,” “A.A.A ~ Argentina.”

Recently, I discovered a Poetry Room. Sadly, I have no access to it.

[ + bar ]

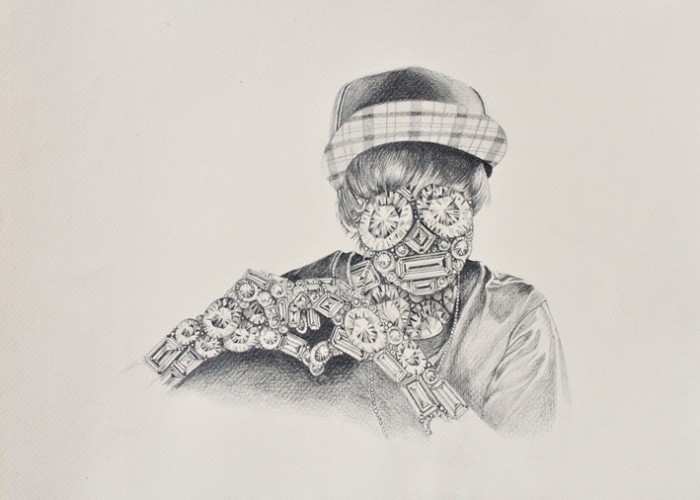

On Luna Paiva’s “Memorias Herméticas”

Andrew Berardini

Even if the meaning of ancient totems disappeared, their meaningfulness has not. A human hand altering nature with purpose, these ancient stacks of stones mark a... Read More »

I’ve Lost Everything I Loved (excerpt)

from J’ai perdu tout ce que j’aimais by Sacha Sperling translated by Addie Leak

I had decided that my name would be Sacha Sperling and... Read More »

Victoria Redel

BOTTOM LINE

As when my father goes back under and the doctor comes out to tell us he’s put a window in my father’s heart.

At last! The inscrutable years... Read More »

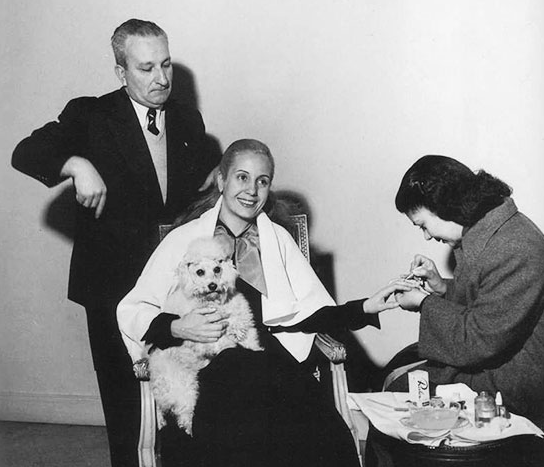

Evita Fashionista

Mariano López Seoane translated by Heather Cleary

A decade ago, the New York philosopher Jennifer Lopez gave us “Jenny from the Block,” an ode to upward mobility... Read More »

sending...

sending...