John Freeman

THE HEAT

At night as the heat’s

warble strummed to

a ticking silence,

and the crabgrass

turned blue then green

then black, the branches

above would relax

and gently pluck my

window-screen, like

the dark-haired woman

who, years later, would

scratch to be let in.

**

UNKNOWING

Your father was born after the earthquake & fire.

Began work at four, buried his mother at six.

Summers he picked prunes in the valley,

the sun searing spots onto his narrow shoulders.

He lost an eye. Blew out his left ear-drum

in a packing plant accident. These things

were what one expected.

He never made friends. They were a luxury,

he could not afford. He smoked for a decade,

through college, when he worked full-time as a

teacher. Nights he dedicated to numbers. Found

pleasure in the orderly arrangement of the known

world. You were a gift, born at the end of the

depression, to his German wife—unaware of

the rubble from which you emerged.

You were a child among the many thousand trees

of Sacramento. Imported to give a desert

valley town some shade. At sixteen you were

given a ’57 Chevy, which you rolled twice

on the way home from football games. Your

license was never suspended. It was too easy

to make such things go away. Your father,

mid-climb into the airless summit of his

unexpected career, did not attend your games.

You had to learn the sting of failure

unobserved. Davis, then Berkeley, then

seminary, where, among closeted homosexuals

and anguished penitents, you felt, in God,

a familiar sense of bruised neglect.

You dropped out; worked as a prison

guard with teenagers put away

after knife fights and bar-room brawls.

One year. Your peripheral vision and drop-

step adjusted, never softened.

We were born in Cleveland, where you had moved

for yet more school, and where you sensed the sinkhole

developing. My mother, cute as a young nurse,

from an Ohio land-grant family which paid her

credit card bills. You lived in the ghetto,

wore zipper boots and drove a dropped ’69 Mustang.

A brick thrown at your head on a passing bus

reminded—you may be an outsider, but your

skin was white.

It took years to conceive. Your gratitude for children

immense. At nights, in Long Island, and then

Pennsylvania, your lips on our heads, were

so kind as to be Unnoticed. We slept unbroken.

I do not remember once having dinner after six.

Our biggest complaint, the wait before we could

race out into the humid falling dark, to hear

the ball’s pop against our new mitts.

Thirty years after you left we returned to Sacramento.

Your mother long since dead. Your father’s two

decades of world travel underway. The sun poured

down on our backs at the swim club, scorching

spots onto our broad shoulders. We trained

like professional athletes. None of us failed.

You provided in your artificial poverty by

adopting an actuarial budget. Everything

would be recorded. We started work before

our tenth birthdays.

We woke to mists, to tinny clock-radio top

forty hits. Slept-walked to the garage, klieg-

lit in the gloaming, where at five you stood

counting newspapers, sprung from their plastic

binding like newborn news. We pedaled

out into the fog as if back into our dreams.

The only sound the squeal and crank of our

wheezing bicycles.

Half-way through the route, our bags like sagged

breasts on our chests, we would come upon your car,

rear-gate agape, classical music aerating the silence.

A light-ship docked among the palm fronds

of an indifferent neighborhood. You fed

us another forty papers, packed roughly and

quickly so that we never finished later than

six. It took me far too long to understand

this was love.

**

OSLO

I’ve been here

before, the hotels

in the bluish light,

squares of ice.

Outside the

opera house

taxi tires crunch

across pavements

of salt, the first

departures. I begin

a letter describing

it all, knowing you’ll

never see it. Later,

I’m down there among

the commuters,

and, for an instant,

it’s as if

you were here. Ice,

lights, the wind’s

knowing sere.

It’s been two years.

* *

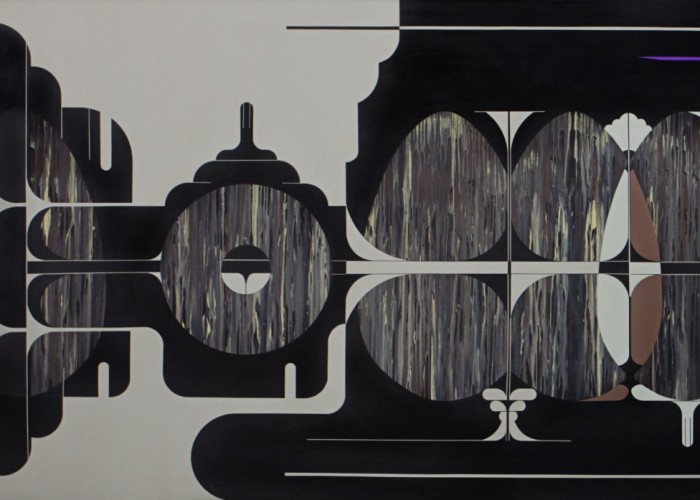

Image: Sofia Flores Blasco

[ + bar ]

Andrea Durlacher

Andrea Durlacher Translated by Anna Rosenwong

It’s something no one regrets.

Menacing rituals arrive like an avalanche

and social norms.

Their arrival scares off any afternoon idle.

Shut the doors.

We’re cast down defeated... Read More »

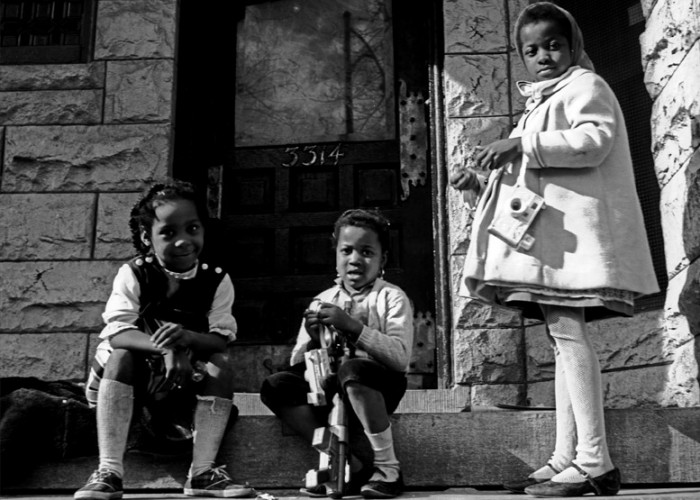

“I’m still falling” — Jeffrey Goldstein on Vivian Maier

Interview by Eliana Vagalau

Jeffrey Goldstein’s life took a very dramatic turn when he came into the possession of a large part of Vivian Maier’s artistic legacy. Now... Read More »

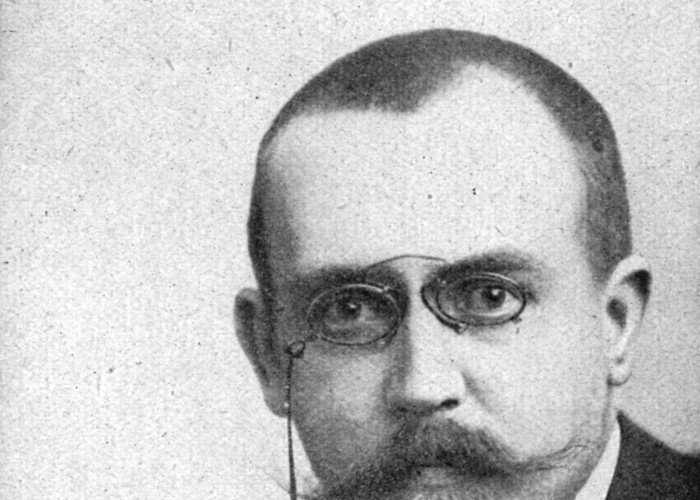

Die großen Bäume. Eine Juno-Novellette.

Paul Scheerbart

Die großen Bäume tasteten mit ihren langen Astarmen immer heftiger in der Luft herum und konnten sich gar nicht beruhigen; sie wollten durchaus... Read More »

The Prouf is in the Vermouf

James Warner

The first account our agency landed was a fortified wine called Clouf. Roland slammed a bottle on my desk and told me to think... Read More »

sending...

sending...