Smoke

Giovanna Rivero

translated by Rachael Small

The pointless memories are the most beautiful ones. I must have been, what, eight years old when this guy with a bird’s name, Piri, came to my grandparents’ house. He’d come to help my grandmother with the little sausage and bakery business she’d set up in her third courtyard. It sounds unbelievable, I know, but the house really did have three courtyards and in the third, as I said, my grandmother had set up a real life steam-powered manufacturing line for chorizo and bread. If you showed up very early in the morning, you could imagine the smoke belched out by the grinders, ovens, crushers, fillers and pots being, logically, the smog that rose in a frenzy from the First World’s last generation of machines.

In what should have been the house’s hall, my grandfather had set up a civil registry where migrants from the interior would document their newborns, newly deceased and newlyweds. Piri called it a job for slackers: pushing the buttons on a toy as though your life depended on it, stopping poor people from giving their children gringo names like Johnny, Chuck or Michael and, for entertainment, cheating against yourself at solitaire. He found the concept of a “writing machine” completely ridiculous, since we were used to the brutal machines that converted meat into a shapeless, reddish blob and then into chorizo.

In the afternoons, Piri’s job was to measure the lengths of hog casing to be used throughout the day. Talking about this may not be literarily correct, but it has to be done. Piri would set the bucket on the floor and, sitting up very straight, using both hands to stretch each section taut, measure out the meters of this transparent fabric that my grandmother would need to fill with ground meat. At the time it didn’t make me sick. There was an indescribable pleasure in the liquid snap the skein of innards made inside the bucket with water and vinegar, and in the serious look on Piri’s face as he used what little math he knew. I noticed that Piri would always keep a little scrap of that viscous membrane in his pants pocket, even though the gut sometimes still smelled like shit. He’d put his finger up to his mouth so I wouldn’t say anything and I didn’t say a word.

One afternoon, my grandmother sent Piri off to run an errand in the capital. He should have come back that night, but he didn’t. My grandmother threw herself heart, soul, and life into investigations worthy of Sherlock Holmes. She interrogated a pair of potential girlfriends, had a true-or-false conversation with a man who bet on cockfights, talked about debts and threats, and finally had to accept the initial statement she’d been given by the driver who was the sole witness, a man from Montero who was kind of touchy but had a good memory. It was really quite simple. Piri had gotten on an interprovincial minibus and paid his way up to Santa Cruz even though he could have gone to Warnes, a town along the way. This, according to my grandmother, only demonstrated that the boy hadn’t planned with premeditation and malice what would later be called in family legend “Piri’s inexplicable escape” or, in the barest terms, “how Piri went up in smoke.”

My grandmother eventually shut down her business, not just because she was sick, but for mysterious reasons beyond this story.

What I know for sure is that we never figured out why Piri got off in the middle of nowhere, in an area with no roads or farms or crops, just grass, trees, and the Sun, floating in the slow death of summer.

A few years later, when our town got its first asphalt road, I went with my grandmother to the capital for a doctor’s appointment—her lungs, the x-rays said, were two damned chunks of coal. Our minibus stopped somewhere and an emaciated boy with a backpack on his shoulder got out and started walking through the grass, between fat cattle and squealing sows, like he was walking toward the Sun.

I pressed my forehead to the window so I could see him better. Would the world end if you walked and walked all the way to the edge? I wanted to get off, too. The evening was immense and warm and in the distance I could see the gleam of a few oil wells, which were said to burn endlessly and occasionally swallow people up in one gulp, like hell. My grandmother read my mind and squeezed my wrist in her calloused hand. She held me back—me, or my desires. Then, as though it were relevant, she said: “men use hog casings to keep from having babies.”

She was certainly good at that: filling something up with magic or ground meat and then destroying it.

* *

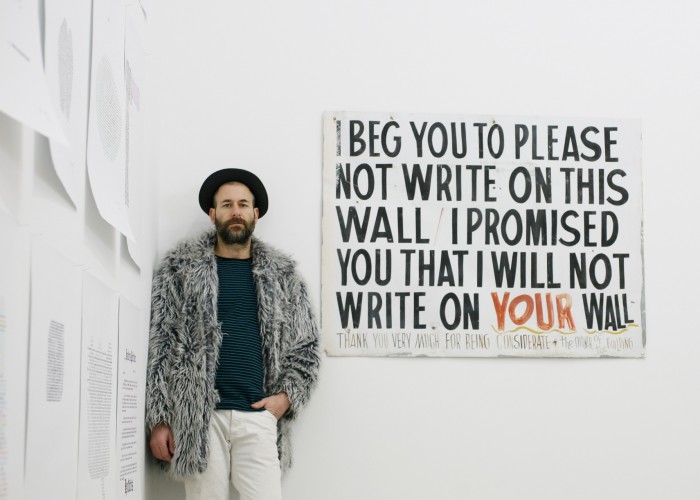

Image: Eduardo Carrera

[ + bar ]

Black Ball

Mario Bellatin translated by Andrea Rosenberg

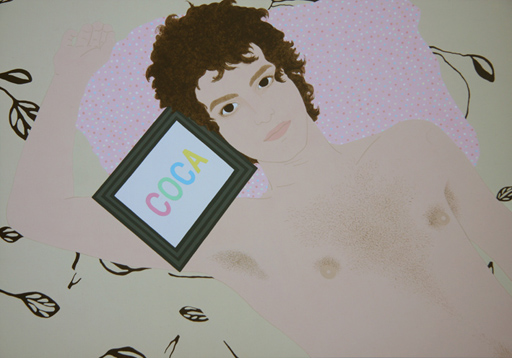

1- BLACK BALL RELOADED

Author’s first look at the bande dessinée Black Ball

Yesterday I received some information about the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal. I... Read More »

After Kenneth Goldsmith: an interview

Michael Romano and Kenneth Goldsmith

I.

I have a bunch of questions but they’re still pretty disorganized in my mind.

So let’s just shoot.... Read More »

Edipo [buenos aires]

Milton Läufer translated by Heather Cleary

It’s true: Edipo is an ugly bookstore. And yet, though this may seem like a contradiction, its most notable... Read More »

![Edipo [buenos aires]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/Screen-Shot-2013-04-20-at-11.16.56-PM-700x500.png)

sending...

sending...