Bestiary

Aaron Thier

Perhaps one discovers the Aberdeen Bestiary in a moment of idleness. Perhaps while searching, as sometimes one must, for descriptions of carnal love between sailors and mermaids. Perhaps on an afternoon of driving rain, the sky rolling like surf, the palm trees tossing their heads, disoriented pelicans sailing past the windows.

How interesting, then, to learn that pelicans typically kill their young and that, having done so, they open up a gash on their own flank and let the blood run over the dead chicks, which brings them back to life. And how interesting to learn that the pelican, with its clumsy prehistoric appearance, is by no means the most peculiar of birds. The bat, for instance, is the only bird with teeth, and bees, the smallest of all birds, are twice as fertile as any other. The peacock, which is also known for its unaffected walk, has the head of a serpent. The hoopoe takes pleasure in grief, quails suffer from the falling sickness, and ostriches are hypocrites.

But perhaps one doesn’t merely discover the bestiary. Perhaps one seeks it out in the moment of one’s greatest need. It may be a matter of life and death to know that bloodstone is effective against poison as well as trickery, or that sapphires will staunch the flow of blood and, as long as one behaves in a chaste manner, will also cure ulcers and headaches and injuries to the tongue. Surely it’s important to know that medus, ground on a green grindstone and mixed with a woman’s milk, cures blindness; that jet is good for a ringing in the ears, cures an upset stomach, and puts snakes and demons to flight; or that smaragdus is a marvelous stone, which, if worn chastely, brings wealth, and if worn on the neck, chastely or not, endows one with persuasive eloquence—but not only that, no, it also cures hemitertian fever and epilepsy, and banishes storms and wantonness.

But now and then one requires solace of another kind. One therefore does well to remember, as one stands by the window in the black watch of night—as one perhaps mistakes the call of an owl for the ribald hooting of a cunning and malicious ape—that diamonds are efficacious against empty fears, and that pearls dispose one to sleep.

And what, indeed, of apes? The Bestiary teaches that the sphinx is a type of ape, as is the satyr, which is easy to catch but will die in captivity because it can only live beneath the Ethiopian sky. Satyrs have beautiful faces but, like all apes, they grow sad as the moon wanes.

When the lion feels unwell, it simply eats an ape, which cures it.

Another type of ape is the dog-headed ape, a particularly ugly animal and one that women are therefore discouraged from keeping in the bedchamber because, as everyone knows, a woman’s offspring tends to resemble whatever she’s thinking of at the height of her ardor, and if there are apes in the room, it may be vain to hope that her lover will offer a sufficiently absorbing distraction.

But whether there are apes in the bedchamber or not, the man who labors to satisfy his impatient mistress, or at least to command her attention to such a degree that any offspring she bears will have his own features, must remember that for women the seat of fleshly pleasure is the navel.

And everyone, yes, everyone should pay heed to the dangers of menstrual blood, which withers crops, turns wine sour, makes dogs rabid, and dissolves asphalt glue.

Does there exist in all the world a more vexing and treacherous creature than Woman? Perhaps not, but at least the man who disappoints his lover night after night, attentive though he is to her navel, and each night slips out of bed, shoulders aside the jeering apes, and goes to stand on the veranda in the mist, may comfort himself with the reflection that things are just as complex elsewhere in the animal kingdom. One does not envy the elephants, for instance, who, in order to conceive a son, walk together to the gates of paradise, where the female must convince her mate to consume the fruit of the mandragora. This he is understandably reluctant to do, and yet only when he has eaten the fruit can she conceive. Later she gives birth in a pool while he stands guard against dragons.

Bears give birth to a shapeless fetus—white in color, with no eyes—which the mother then sculpts with her mouth.

Panthers give birth only once in their lives, which is perhaps an explanation for their diminishing numbers.

Bees are produced from worms, which are themselves produced when one beats a dead calf with a stick. One may produce hornets in the same way by substituting a horse for a calf, and wasps by substituting an ass.

The animal kingdom is indeed rich and varied, and there is no more complete zoological guide than the Bestiary, from which one also learns that if a lion eats too much, it inserts its paws into its mouth and pulls some of the food out, that hyenas live in tombs, that snakes despise clothed men and fear naked men, and that if a beaver fears it’s being pursued by a hunter, it will gnaw its testicles off and throws them in the hunter’s face, knowing that its testicles are the object of the hunter’s desire. Very effective medicine can be made from a beaver’s testicles.

The bite of the spectaficus turns a man to liquid.

A dog that touches a hyena’s shadow can never bark again.

Wolves can eat wind.

But enough, enough. It’s all very well to stand about contemplating the beauties and horrors of nature, but when one is again idle and finds oneself alone in the yard, studded with jewels and stones, a disappointment to one’s lovers, a disappointment to one’s self, staring in horror at the boiling sky, what then? What then?

The Bestiary does not neglect the spiritual life, as indeed how could it? The lesson of the beaver is clear: One must cut off one’s sins and throw them in the devil’s face. And in the hyena, which imitates the sound of a human vomiting and devours the dogs that come to investigate, we have a figure for those children of Israel who, depraved by luxury, worshipped idols. The apes, the eternal apes, whose hind parts are foul, teach one to fear the Devil, and the weasel, which conceives through the ear and gives birth through the mouth—except when it conceives through the mouth and gives birth through the ear—represents those people who listen to the divine word and yet pay it no heed.

Strictly speaking, man is formed from soil, and to soil he must return. Small wonder that one weeps in the shower. The roads to Hell are many, and no precious stone, no matter how chastely worn or upon what part of the body, can guarantee a place in Heaven.

Ships sail more slowly when they carry the right foot of a turtle. The excrement of the caladrius cures cataracts. The monks are laughing, always laughing. One must keep the image of Christ ever before one’s eyes, for Christ is a lion. He roams among mountain peaks and obscures the scent of his divinity with his tail. Christ is a panther. He is gentle and multicolored, and on the third day after he feeds, he rises from sleep and gives a great cry, and from his mouth comes a sweet perfume. Christ is a palm tree, for he has hair and has already grown to his full height. Humble yourself as does the elephant, which has no joints in its knees. Regard yourself, as does the dove, with your left eye, and with your right eye contemplate God. Christ is, after all, a pelican, desperate and wheeling under a tormented sky, for he lives in solitude, and has no pocket in his stomach in which to retain food, and as he kills his young with his beak, just so does he reject sinful thoughts and deeds.

* *

Image via The University of Aberdeen

[ + bar ]

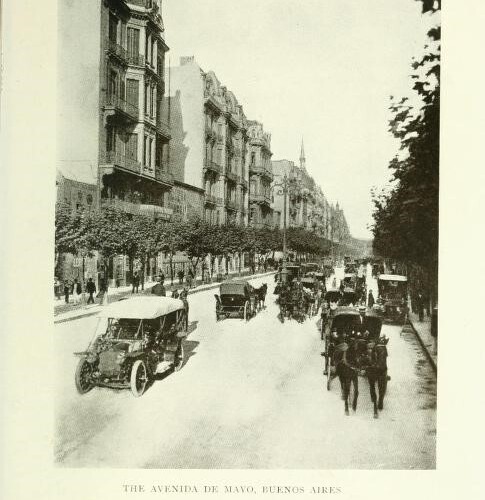

Argentina and Uruguay (excerpt)

Lucas Mertehikian

We don’t know much about Gordon Ross. We don’t know how long he lived in Buenos Aires nor where exactly he had come from. The first... Read More »

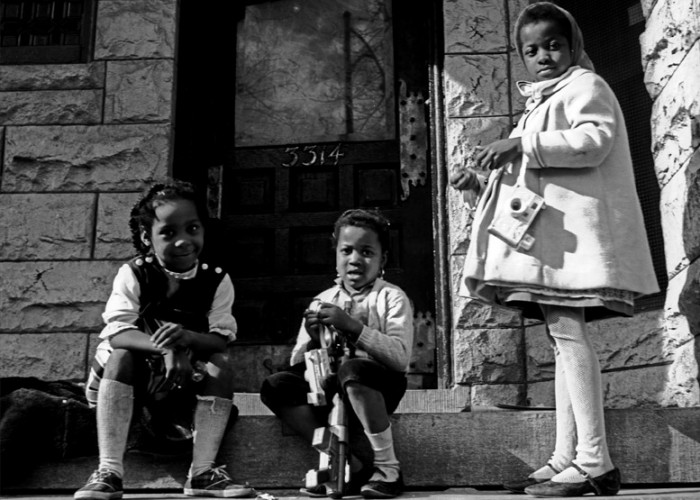

“I’m still falling” — Jeffrey Goldstein on Vivian Maier

Interview by Eliana Vagalau

Jeffrey Goldstein’s life took a very dramatic turn when he came into the possession of a large part of Vivian Maier’s artistic legacy. Now... Read More »

Dubitation (a selection)

Martín Gambarotta Translated by Alexis Almeida

Here, the water is different, the artichoke

leaves are different, everything is

in essence, different,

but he who takes the bottle from the refrigerator

and... Read More »

Bellatin and Japan: an Interview

Mat Chiappe translated by Anna Hardin

Mario Bellatin once said to me: “I don’t want to go to Japan.” I don’t know if we went on talking... Read More »

sending...

sending...