Dragon in Clouds

Juan Carlos Mondragón

translated by Leah Leone

Until the middle of the afternoon of the day before yesterday, I thought I had a good angle for the article I was writing about an incident in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904, as a way to further the discussion about the submarine strategy employed during the blockade of Port Arthur. While researching, I also worked on my courses for the upcoming semester—I teach Latin American History at an Italian university and lead a seminar based on Eugen Millington Drake’s Battle of the River Plate—to bring focus on the key elements that had contributed to the stunning efficacy of a joint strike at high seas, the incalculable factor that had made it a classic battle in all of military history, without arriving at a convincing conclusion. When the logical connection has rusted over, all one can do is feel his way around until, in some corner of the tapestry, the inverse of the most likely scenario, the Licorne appears out of nowhere.

So that was until Monday; I liked the idea of being the eighth speaker at an upcoming conference in Cartagena, where I would read a paper on techniques for escaping detection by enemy radars. I hoped my talk might be remembered like Ridley Scott’s Alien, the eighth passenger of the 1979 film: the chimerical stowaway aboard the Nostromo, invented by Hans Ruedi Giger; I wanted to cobble together a similar creature, but instead of issuing from infinite space, where no one can hear you scream, it would emerge from the watery abyss. The Russo-Japanese war of 1904 was also a monstrosity of history, and the clamor from the world of the dead returns to my field of interest in periodic blasts.

Around eleven in the morning, I realized that nothing could be done if I forgot to include the words “cherry tree” in my article, correspondingly evoking the sound of rain falling on a wood cabin on the banks of the river. No one who exalts in all things related to the burning sea and to war can escape the hypnotism of the Japanese. The Mikado and his subjects, stranded on an island, defenseless against the wiles of nature (as compared to the atomic insanity of men), found in the sea a delirious territory for conquest.

The impulse to mention the cherry tree in bloom had been born of a recurring and prophetic dream brought on by the digestion of last night’s sushi dinner with three colleagues, its resulting loose stomach and my recent re-readings: Togo, by Vice-Admiral Nagayo Ogasawara and the Memorias del General Kuropatkin, edited at the beginning of last century in Barcelona by Monanter and Simón.

My plan for the article, all that about being the eighth speaker at the conference, fell through. It was postponed several weeks for random reasons and sentimental convalescence; I wanted to write the subjective part of the incident that kept stirring around in my mind, to evoke the two mutually exclusive facts that later intertwined, and to do so in such a way that this concept of warlike ardor—when you consider massacres en masse, thousands dead after just one day’s assault, like the third attack on November 3rd, which left thirteen thousand Japanese dead (General Yamamoto died on September 20th, and on December 13th, a grenade killed General Kondratenko, the hero of the resistance)—would evaporate just like the line of the horizon on the Yellow Sea. I am clearly not in the ideal frame of mind to do this and retreat is unthinkable. It will just take a few minutes and after that, once I’m free, I might be able to do something worthwhile today.

It happened just recently, June 18th, Saint Leonicio’s Day, close to the deadline I had given myself to finish the paper. I kept putting off the time I needed to write with the necessary concentration. The project I’d committed to loomed in my thoughts; it had a catchy title, suggesting a tangential homage to the engineer Isaac Peral, illustrious son of the city to which I’d been invited. I was about to settle in when, on my way to make coffee after splashing my face to refresh my ideas, I opened my email.

Waiting in ambush was a message for me; someone from the country of my youth, a dear friend and fellow student, informed me that Jorge Medina Vidal, our literature professor at Institute of Professors Artigas, had died the day before. I had studied Letters briefly; that was before dropping out and moving on to Arms, which changed the nature of my work. The news sank me into a blurry melancholy; memories of a wild band of youths, the path that leads one to teach literature, conversations in the cafeteria and student idylls buoyed up by books on theory. Medina Vidal’s voice, his missing finger as a point of distinction and his manner of speech that I can hear again merely closing my eyes.

I’ve been living in Trieste for some time, but I was born far away and now I’m on sabbatical in Paris for the semester, to be close to the Marine Museum, its impressive archive, and far from the family for awhile. I rented a studio in Montparnasse that burns up half of my grant money and the countdown to the end of my stay has already begun. Medina Vidal spoke little of Paris, which is no longer the capital it once was in the nineteenth century, and spoke instead of the French poets. All that’s new in my temporary home are the public bicycles meant to rid the atmosphere of carbon atoms, a fake beach on the banks of the Seine, the comedy of those in power speaking words of resigned decadence, a few meteorites arriving from nebulous distances that occasionally cut through the sky leaving a persistent trail.

I had prepared that day by clearing everything from my agenda to move forward with the article and wouldn’t be able to—that sadness travelling back from my youth interrupted me. Then I remembered having seen a red Mount Fuji on the wall in the Metro; it was in Place Monge Station on Line 7, during the passenger accident last week that had stalled service for an hour—another suicide circumventing its name.

The sign announced an exhibition of artwork by the master Katsushiba Hokusai, exceptional for the quantity of material on display. Would Medina Vidal have liked Hokusai’s prints? Without thinking twice, I decided that was exactly what I needed, and an hour later I was on Bus 92. I wanted to visit a nineteenth century without the battle fields I had memorized in my National History classes, without passages by Benjamin or Goya’s disasters of war.

Twenty minutes later I stepped off the bus at the Pont de L’Alma stop, a place that has garnered international fame for being the site of the fatal accident of Princess Diana, bosom friend of Elton John, godmother of the fight against antipersonnel mines in Africa and mother of Kings, as the Three Witches would say of fair and foul at once. To the site, in pilgrimage—defining what is now held sacred—people bring bouquets of fresh flowers, imperial violets, colored candles and handwritten notes expressing pain for their fallen sister—writing a fairy tale with a diamond tiara, a kind of sugary sentimentalism falling somewhere between late puberty and gossip magazines.

The midmorning moving toward afternoon was oppressive with its threat of rain, the stormy sensation that leaves you longing, and which finally pours out, soaking your clothes and you, to the bone. Maybe it was me, weighed down by the death of a teacher so far away from my immediate surroundings. His classes on Juan Rulfo, speaking with the forgotten dead, and digging out like the pit of a peach the clues to “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” were my literary education and could not be countered—but then, why and in the name of what would anyone try—to the end of my days.

The sky in that part of the city, because it is so near the Seine, is a close material presence that descends like the Holy Spirit in biblical scenes from baroque operas. You could pick up the scent of the storm on the clouds like a wild animal in a meadow. There was something of the bucolic atmosphere of the fields of Tacuarembó, before a spectral band of suicidal gaucho warriors bearing lances ripped across the plains. Yet the sphere of the sun shone insistently, to the point of blinding me, barring the way to that outpouring of grief, allowing me to remember a poem of Jorge Medina’s entitled “The Grand Theater”:

Remember Salvadora Cairón,

Andalusian bolero singer around eighteen seventy,

with an “arrogant presence.”

Married to the actor José Valero who made her

a star around eighteen seventy-five.

Renowned for the DIFFICULT part of Doña Constanza

in the play: “La Campana de Almudaina”

by Palou y Coll (also a playwright)

who retired, to private life, because of the cursed

disappearance of a steroid, the

“17-dihydroxypregn-5-en-20-one” which became

“11-desoxy-17-ketosteroid”

and she grew old

like you, like all of us,

like me,

until its cursed presence can be checked

and then we’ll have more time

for bolero

for love

for theater.

After theater, love and bolero in the 16th Arrondissment, I walked steadily up the Avenue du Président-Wilson and four blocks later arrived at the Place d’Iéna. You’ll never lose your way if you keep your sights on the theoretical; after all, we read science fiction and we’ve never been in a space capsule, or landed on an asteroid invaded by insects; we believe in astrology but have never touched a meteorite extracted from the planet of the dead. On the right was the Guimet Museum of Asian Art.

Up ahead was a line of people waiting to get into a show mounted on the most delicate brackets one can imagine. The human serpent wasn’t too intimidating, but its slow advance had me asking why all that humanity, that morning, despite the weather that threatened, when there were so many other things to do, wanted to see Hokusai’s work, and wondering if I wasn’t wasting my time waiting, instead of hunkering down and writing my article about immersion strategy.

Not that they were dramatic doubts I had, but an hour and a half later I had the answer I needed. In that disconnect from the present, I lived an experience so intense that, if I approach it modestly, I might be able to begin to explain. An outline of words leaving ephemeral evidence of what I experienced, a note they enunciate. Slow immersion into a mystery of existence that I had overlooked in recent years and of which the death of my friend brutally reminded me.

As if writing sought to be the sound of a paintbrush impregnated by Prussian blue (“talking of Michelangelo”) on rice paper and prepared in the dim light of the studio, when an autumn of ochres erupts and the rains can be felt on the skin of one’s forearm. A trace of what has been lived and forgotten suspended in that ephemeral exposition. The delicateness of an illusion of a haiku enacted. If such a thing were possible in the deceptive world, if it’s not another poetic utopia, destined for the trashcan. The need to dominate the discipline of Kendo to be able to cut life in two halves with one slash of the sacred sword, where the blade is the sadness of the passing day; knowing that the emotional connection and the memory of what I had seen was an experience more incisive than any I could expect in the coming weeks.

Appearance and awareness, memory and desire. A drawing inscribed on the retina of the viewer: regarding a bridge inconceivable for its lightness and length. An asymmetric bundle of lotus flowers floating in the swirling current, the words “cherry tree” and their characters arranging themselves seamlessly in the vertical phrase. A nonexistent bird sought for the sunflower color of its outstretched plumage. The hundred-year-old cherry tree in bloom so suggestive of something at its end.

I paid the seven-euro entrance fee with my credit card. There was a second line in which to wait before entering the dimly lit halls of the exhibition. We would cross over to the other side of the time divider. To the left, the show designers had hung works meant to create an ideal atmosphere for emotion. On the right was a list of dates to help orient visitors.

The life and work of Hokusai took place took place between 1760 and 1849, the period in which my Latin American homeland was extracting itself from colonial magma. The artist coincided with Napoleon in Madrid and Goya recording the disasters of the affair. Another world in alchemic transformation by firearms, horses falling in Andean mountain passes, lances piercing loyalist hearts. Unaware of these events, the master on the other side of the world illustrated poems of his contemporaries, while Salvadora Cairón’s youth slipped by in Andalucía.

He made visible anthropomorphic ghosts, set erotic fantasized scenes where male sex organs impose themselves in ritual disproportion.

A young woman with Asian features let me into the luminous heart of the show. I stopped to read a text about the process of creation over the course of one’s life and translated it into Spanish in my head:

From the age of six I have been obsessed with drawing the forms of objects. By the age of fifty I had already drawn an infinity of objects; but I would not approve of anything I produced before the age of seventy. It was only at the age of seventy-three that I came to understand somewhat the form and true nature of birds, fish and plants.

And so, by the age of eighty, I will have improved considerably; by ninety I will truly understand the essence of things; at one hundred I will have definitively attained a higher state, indefinable, and at the age of one hundred and ten, be it a point, a line—everything I draw will be alive. I would ask of those who live as long and who outlive me to see if I am true to my word.

My God, I said to myself as I read that and realized what we lose along the way in our final years. Creative reflection was incapable of producing a thought with such profound detachment and humility, such immersion in the craft when Time devours the infinitesimally short course of an existence: a conscious life is the only haiku we will write in the face of the indifference of the cosmos, while our steroids transform themselves, condemning us to grow old too soon.

I made my way through, not looking for anything in particular, for something concrete waiting there for me that would move me unexpectedly. Pausing before landscapes with and without people, I thought: this is a perfect version of an eternity that never existed.

Whosoever can write that wooden bridge uniting the moonlit night and the irrational clarity of the dawn will reach the perfect poem, a challenge often put to us by Jorge Medina, who had just died, in his courses on modern poetry.

So you have to wait until you’re seventy-three to understand the aesthetic project of creation and nature. And men’s hunger for war in 1904. There’s no hurry, I’m still far from that age and as of that morning it would be sixteen more years. Maybe it’s true that art is ongoing, and besides, it doesn’t matter, and we refuse to heed this out of an amnesia that resembles stupidity, and for good reason.

Prints and original books, irreplaceable engravings and girls playing the shamisen with steel strings.

A nameless philosopher contemplates the disconcerting flight of butterflies.

Trial sketches for large projects.

Conchs and lobsters.

Samurai armor and ritual swords.

Manga of the workers and daily life on the islands.

In the last room were the two paintings the master had produced during the final months of his life, a testament without being one, and which death imbued with the impression of being posthumous.

“Tiger in the Rain” and “Dragon in Clouds”.

Sublime kakemono-style works reasserting respect for the tradition of form to the precise millimeter. The two essential animals: one whose feline prowl emerges from the depths of the jungle and the other who flies carrying the fire of men’s imagination, and vice versa.

It was there not to admire, rather remembering in peace and leaving open the flow of correspondences. The firm, knowing hand of Hokusai capturing the flight of the fantastic Dragon amidst the clouds. Creature of fire, that eighth passenger of men’s imaginations carried me far through time.

And I went back thirty years. I heard Medina Vidal’s voice, perhaps on a morning like this one, as if he were, at this very moment, reciting a poem by Guido Cavalcanti, as if he were there and we were too. At that unmanageable intersection, this Ash Wednesday there can be no writing of articles, much less the one by the eighth speaker on the program set for Cartagena. After leaving a written testimony of what I experienced in that portion of the day I feel better. Having paid an outstanding debt to the literary education provided by beloved teachers. With the integrity of having done what needed to be done, waiting to make it to age seventy-three, 2024 if the gods allow, and crossing over is no safe bet either.

When I went outside again, the line of waiting visitors was barely moving. It was a fantastic anaconda in the midst of digestion; a wind from the East rapidly shook the trees of memory in the circle of the plaza. The thought of the war for control of Port Arthur attacked my mind and I calculated that in 1904 Hokusai would have been 144 years old. Had he not grown old like Salvadora Cairón and Medina Vidal, like Cavalcanti and all of us.

I sped up trying to reach the entrance of the Iéna Metro, to get ahead of the rain that was required to wash away the weariness of the city. I wondered whether I’d closed the windows of the apartment tightly enough before leaving; that wouldn’t matter if I could reach the winged Dragon of memory, the imaginary creature of lost youth. It was right there, corralled by an internal flame, among those travelling clouds, like a colorful kite in an electrical storm raging over Montevideo, the coquette.

* *

Image: Katsushika Hokusai (18th century)

[ + bar ]

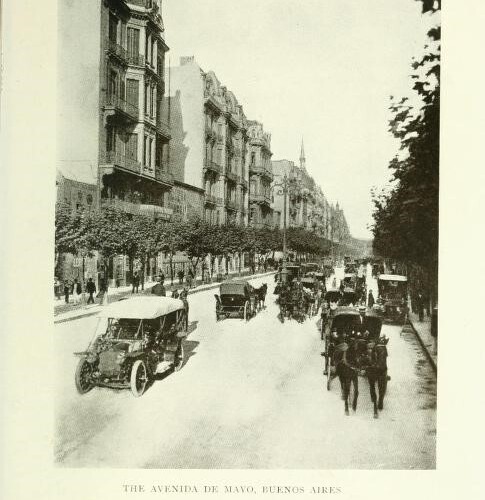

Argentina and Uruguay (excerpt)

Lucas Mertehikian

We don’t know much about Gordon Ross. We don’t know how long he lived in Buenos Aires nor where exactly he had come from. The first... Read More »

O único final feliz para uma história de amor é um acidente

Não posso vê‐la esta noite

Tenho que desistir

Então vou comer fugu

Yosa Buson (1716‐83)

1.

Antes do sr. Atsuo Okuda abrir a caixa, tudo estava... Read More »

The Reversal Spell

David Leavitt

The day that Paris was declared an Open City, I went to say goodbye to the Baron. He was one of my oldest friends.... Read More »

Dubitation (a selection)

Martín Gambarotta Translated by Alexis Almeida

Here, the water is different, the artichoke

leaves are different, everything is

in essence, different,

but he who takes the bottle from the refrigerator

and... Read More »

sending...

sending...