Marilyn Monroe, my mother

Neda Miranda Blažević-Kreitzman

translated by Ellen Elias-Bursac

Many people wrestle with discomfort and fear when they travel by air. Dino Lučić and Veljko Linić were not that sort. The two young businessmen from Split, Croatia were now reclining, relaxed, en route from Frankfurt, Germany to Los Angeles, wrestling with the urge to sleep that was pulling down their drooping eyelids, hampering their adventuresome spirit to gaze out the little window at the vivid blue sky through which their speedy vessel was winging its way.

Dino Lučić was tall, slender, dark-haired, while Veljko Linić was medium-height, muscular, and blue-eyed. Both worked at Jedrogradnja, a company that built and sold speedboats and yachts. Their best customers were Americans. The salesmen for Jedrogradnja had been working with B&B Brothers, Inc. of Los Angeles for nearly four years.

Lučić and Linić had been friends since their teens. When the Homeland War broke out in Croatia in 1991, their generation was just finishing high school. Dino, who had an aunt and uncle in Canada, moved to Ottawa and attended the university there. He graduated with a degree in international commerce and finance. His studies gave him a mastery of English and French. Soon after he earned his degree he found an office job at Sal-Mon, a large fish-processing concern. He worked hard and with spirit. Two years on, his work ethic, alacrity, and eye-catching good looks earned him advancement to the post of general manager’s assistant in the finance department at Sal-Mon. Working in a global marketplace meant traveling often to different parts of the world: China, Japan, the Middle East, North and South America. This new, high-paying job of Dino’s was physically and mentally extremely demanding. But he was resilient and ambitious. He often met attractive women on his travels and he would draw their attention like a rare, glittering jewel. But the demands of his job meant he was not yet ready for monogamy. Fleeting trysts with women he met at meetings, international trade fairs in the food industry, and in bars up and down the Americas, Asia, the Middle East and Europe suited Dino just fine emotionally and physically. He was sure his life was perfect until one night, when, soon after his thirty-second birthday, the elusive power of nostalgia evoked images of his parents, the city of Split where he was born, childhood friends and his high-school sweetheart Karmela—an alluring brunette on whom almost all the boys in school had had crushes.

Two months later, after lengthy bartering with nostalgia and his bosses at Sal-Mon, Dino quit and back he went to Split. Within three months he married Karmela, a medical technician employed at the City Pharmacy. She was divorced and had a five-year-old boy.

His old friend Veljko Linić came to their wedding. A marine engineer, father of two girls and husband to Marijana, an attorney, Veljko worked as a ship designer and builder at financially shaky Jedrogradnja. He was hard-working and quiet. The only subjects he talked about at length and with spirit were ship motors and the construction of all manner of boats. So his friends dubbed him Veljo Mut-or. But the derisive nickname did not prevent him from winning the acknowledgment of the Association of European Shipbuilders for an innovation—a part installed in the safety valves for the cooling system of a motor. Several Scandinavian and German shipbuilders offered him a good job, but Veljko flatly refused them all, saying, “I would hate it, some day, with us living abroad, for my kids to be talking to me in some language I can barely understand.”

The two old friends picked up smoothly from where they had left off fourteen years back. Mate Škoro, director of Jedrogradnja, offered Dino a job. Škoro was right in reckoning that Dino’s versatility with world markets, foreign languages and cultures, and Veljko’s engineering flair would help Jedrogradnja break onto the overseas market. This simple calculation harnessed the two old friends in a successful team on which both of them were the helmsmen and the crew members. Now, while the brisk winds and high seas on the Pacific vied to buffet the rocky and sandy beaches of western California, their rugged sails served able sailors and windsurfers as a natural fuel for escapades that defied bewildered gravity.

A light gust of wind jostled the plane in which Linić and Lučić were dozing. The shudder woke them. They shot each other groggy looks. After a second or two, Veljko smacked his dry lips; Dino rubbed his eyes. Nothing serious, just the wind pecking at the wings. Then they both turned to the window, jointly craning their necks. Into thirsty view floated postcard vistas of the Pacific. Its vast wrinkled skin was flecked with white, blue and red yachts speeding over the water like romping dolphins. Some were made by Jedrogradnja. Grinning, Veljko and Dino watched them slice the wave crests, and twinned thoughts danced through their heads. Both were sure their new motor launch model, the ST22, and the slogan Jedrogradnja had chosen for it, Hvatajte vjetar s nama! Catch the Wind with Us! would catch the fancy of Americans.

As the plane from Frankfurt came in to land at LAX after nine exhausting hours of flight, and as the sun’s glowing May orb was moving slowly toward the flat Pacific horizon speckled with gold glints swelling on the meshed ocean surface, there were still heeling sailboats and perpendicular yachts about.

Although Lučić and Linić had already been to the city of many-colored angels three times, they were suprised each time anew while out on the broad streets, the corners, the avenues by things that were fresh, challenging and even downright astonishing. Last year they had, for instance, stumbled upon a small square where a young man, his hair dyed orange, face covered in tattoos, was performing an art piece (or was it a circus act? Dino and Veljko weren’t sure) with a green iguana, three feet long, in his arms.

For his show with the iguana, the performer was demanding a dollar bill from each member of the audience. He would also accept coins. While a few bills and coins dropped into the upturned red hat a step away from him on the sidewalk, he cautiously inserted the long pink head of the iguana into his mouth and then slowly brought it out. Bedecked with long ossified spikes, the reptile’s head was like a flesh-and-blood crown that could very well pierce the roof of its master’s mouth. Finally, as the iguana’s body stilled to motionless with the monotonous ritual movements, the cold-blooded performer began pushing the lizard’s head farther and farther down his throat.

The onlookers reacted in a variety of ways. Some barked with nervous laughter, others dismissed it with a shrug, voiced disgust, cheered raucously “Yeah! Yeah!”

An overweight woman in a flowery dress began emitting little shrieks, and an African American man exclaimed loudly: “Whoa, bro, where does the man stop and the beast begin? Poor thing!”

Dino and Veljko shot each other glances. Their eyebrows arched as they turned, finally, and left the square.

They were expecting, this year, that the Los Angeles array of street shows would be replete with swallowers of exotic animals, flames, and sharp knives.

While purple twilight suffused the sky above the city of angels, already lit by thousands of lights, the two men from Split waited for a cab on the sidewalk out in front of the big three-part airport entrance. Black sports bags holding laptops hung from their shoulders. Next to their feet were small dark-blue suitcases. Lučić and Linić eyed the surroundings out of habit in case they might catch sight of some of the local color whose appearance and behavior might rock their boat, or see a pretty girl to evince a sigh. Their perusal was halted by the penetrating voice of a woman driver who pulled up with her blue and green taxi right in front of where the men from Split were standing.

“Gentlemen,” the driver addressed them slowly as she stepped out of the car.

“Good evening,” answered Dino in accent-free English, swiftly picking his suitcase up off the sidewalk.

Veljko followed suit, nodding at the platinum-blond cabbie. His mute greeting also allowed him to take the precise measure of the driver’s looks and age. She was attractive. Veljko couldn’t pin her age down exactly. Somewhere between thirty and forty, he thought.

The lady cabdriver smiled. She knew what sorts of questions were spinning around his head. She stoked Veljko’s fancy by lightly flicking a stray curl from her smooth brow, tucking it behind her right ear. But the wayward lock bounced back to where it had been.

Veljko smiled warily. The cab driver decided to end the little game, she spun around and went over to the trunk of the car, swaying her wide-set hips. Just before she stopped, she flicked the tendril-like curl back from her right eye with a flirtatious snap of the head. She was certain that Veljko still had his eye on her so she carefully adjusted the plunging neckline of her pink shirt. The shirt, speckled with yellow-brown leopard spots, clung close to her robust torso.

The woman’s dark purple pants clearly outlined her firm, round buttocks. Her blue high-heeled tiger-striped sandals showed she was a lover of wildlife, a regular at a weight-lifting establishment, and a reasonably good imitator of Marilyn Monroe. (Los Angeles was a mecca for female and male impersonators of the famous actress).

After Veljko and Dino placed their luggage in the trunk they were both stunned by grogginess and exhaustion. The warm California air and the nine-hour time difference suddenly hit them like a giant pendulum. They broke out in a sweat and could hardly wait to get to the hotel and a shower.

While they clambered into the back seat, the platinum-haired driver asked them in a leisurely tone, “So, where to?”

“Hollywood, Hotel Luna Luna,” said Dino, dabbing at the sweat on his forehead with a tissue.

The taxi driver nodded, switched on the A/C, and off they went. As they exited the airport and pulled onto Sepulveda Boulevard, the woman glanced over at the seat next to her, where a brown cardboard box lay, filled with brochures.

It was almost nine o’clock at night. The glaring neon lights along the street, the massive windows on the tall buildings and the giant billboards with splashy ads gave the people of Los Angeles the illusion they lived on a bright night-time star.

After a few minutes on the road, weary Veljko fell fast asleep. His mouth dropped open, his left arm stretched along his body, his right slightly bent at the elbow. He looked like a slumbering boy on a canvas by Michelangelo Caravaggio.

The driver, who had been checking the rear view mirror from time to time, now trained her eyes on it. The reflection of her blue, softly smiling eyes sought the reflection of Dino’s dark gaze.

At first he didn’t notice her. He stared, expressionless, through the window, shifting positions in the seat—seeking a more comfortable angle for his long legs.

The driver, however, was patient. For the next few minutes, she’d look up at the mirror at regular intervals, knowing that the tall man in the seat behind her would finally feel the reflection of her eyes on him. And he did.

“In LA for work or fun?” asked the woman when the reflection of her probing gaze in the mirror met with the mirrored reflection of Dino’s sleepy eyes.

“Work,” answered Dino tersely. He was in no mood for talk.

Clearly up for a chat, the driver was not so easily dissuaded. “But a little fun in LA would do no harm, am I right?”

“Of course,” said Dino, knowing where such conversations usually led: a boring disquisition on the weather, tourism, and the other usual taxi topics.

“I assume that when you are out to have fun you make time for reading,” continued the cab driver softly.

Her assumption startled Dino. Reading for fun in Los Angeles? She must be kidding, he thought. And then, again, maybe she wasn’t. His quick mind flew to the thought that this might be some Hollywood code word or ploy, a surprise query with which traffickers in various illegal activities, maybe drugs and prostitution, lured clients into their vile commerce. Reading. Reading what? Dino went on weighing his mental questions. Books? What books? Minds? Dreams? Palms?

As these thoughts shot through his mind, a small ironic grimace playing on his lips. He was a businessman and he knew nearly all the tricks of the trade for the sale of almost anything to potential customers. But he had never until now been asked by a cab driver, man or woman, whether he had fun reading in the city he was visiting. Serious reading.

“I know, my question is unusual in professional or social settings such as this. But there you have it. I like reading so it strikes me as logical to chat with passengers about books,” she said, reading Dino’s thoughts.

He shifted again in the seat and nodded. Still wary, he waited for her to make it clearer what she was after.

She did so readily, saying, in a chatty tone: “Many of my customers come from all over the world and I often hear from them the names of writers who have written engaging books in their language. If I may, who is your favorite writer?”

Dino rolled his eyes like a school kid and sighed. He still wasn’t clear on where to go with this. Should he launch into a quasi-academic discussion with the cab driver who sounded as if she had studied English literature or something, or should he tell her he was worn out from all the travel and the only thing he could think of was sleep? He almost told her he could hardly wait to throw himself onto a bed, and then she turned to him and grinned. In the muted light of the taxi her face looked youthful and fresh.

Dino gulped. He thought perhaps this was not the best moment to mention bed and flinging himself onto clean sheets. But what could he say? That he had no favorite writer. That he mainly read books by economists and bankers. Maybe he should yawn and make the excuse of being groggy. But then the driver might ask him where he and his friend had come from and how long they’d be staying in town. No, he did not want to venture into a broader conversation with the driver.

As if she were easily reading Dino’s indecisive thoughts, the woman turned her soft profile to him again and said in a soothing voice, “You probably work hard and don’t have much time for reading. I get it.”

“Indeed,” mumbled Dino and deeply inhaled the air-conditioned air. His throat began to ache. Little stabs of pain stirred panic in his gurgling gut. The last thing he needed was a sore throat. He shouldn’t have drunk so much ice water on that airless plane, he thought while shallow flushes of spittle forced him to swallow again and test the pain level in his throat.

The driver took Dino’s silence as encouragement to continue the conversation about reading and her favorite writers. “Surely you have heard of William Saroyan. The American writer. What a playwright. Better than Tennessee Williams, at least for me. I guess we all have our favorites. Am I right?”

And without waiting even a second for Dino to respond, she went right on in a lilting voice, “That reminds me of this anecdote about Saroyan. When talking with some journalist guy he said that us readers ought to finish a good book feeling worn out, exhausted. Isn’t that just too cute?”

Finally choking back the spit, Dino wanted to say that he was, himself, pretty worn out, just as if he had read the most recent book by the Saroyan guy, but that he wasn’t up to talking about it because he was so bushed. Then he was unexpectedly prodded by vanity and wanted to tell the pretty cab driver that over the last fifteen years he had read an armful of novels and plays, American and modern classics, and that he’d be able to hold forth on them till dawn, but sadly, was unable to because his throat was so sore. At the same time an alarm went off in his head warning him to watch it. What if the driver used his boasting for a new assault, into which she would, undoubtedly, weave mention of heroic Russian classics about which he knew next to nothing. He had seen the movie version of War and Peace on television. Too many characters and romantic twists. Too little real action. He had fallen asleep on the sofa before this bumbling guy, Bezukhov, if he’d remembered the name right, married a woman he wasn’t even in love with. What a soap opera, thought Dino, yawning.

The driver shot Dino a quick glance again in the mirror. “Have you read anything by Saroyan?” she asked softly.

This time Dino could not retreat to the defense of silence. Though he had never heard of this William Saroyan, he mumbled, “Yes, yes, Saroyan knows what he’s talking about.”

The patient blonde turned toward Dino and glanced meaningfully into his eyes.

He was immediately anxious that his throw-away lie might embroil him in a suggestive yet meaningless conversation about some complicated book written by this Saroyan guy and the amount of exhaustion which, he, Dino, had felt when finishing it. (He had been so tired he had barely been able to muster the strength to shut its sad cover.) But now, again, he did not allow himself to be drawn into a pointless banter about books. He did not want to lie and say he had read them. He followed his decision by lightly clearing his throat. He hoped his strategic coughs would let the driver know he had a cold and could no longer talk with her.

But the tireless woman would not let Dino off the hook. And besides, it was not every day she had such a handsome customer. So she pounced on him with new details about Saroyan and herself. “See, Saroyan, in a way, is my literary and human ideal. Like me he was born in California. His parents came to America from Armenia. His father died when he was three. The family fell apart. He, his brother and his sister ended up in an orphanage. Later they were re-united with their mother. Life was tough. Saroyan, who had nothing going for him but a sharp eye for observation, began writing about the world and himself. And there you have it! America and the world got a new genius! Isn’t that something?”

Dino nodded and sighed hopelessly.

The driver added nonchalantly, “I, too, have tried my hand at writing.”

Dino scratched his head. What he had feared most was happening. The cab driver was an unappreciated author, longing to talk about herself and her writing. A phantom author. This was her plan. To bombard him with the stories she would never write. Gee, everyone wants to be an author nowadays. What is the appeal? The observation that the world is screwed no matter what angle you use to look at it? he wondered, painfully swallowing the spit that had pooled, despite his efforts, in his mouth. He wrapped the fingers of his left hand around his chilled neck and coughed again, intending to let the hopeful driver-author know, with this gesture and the clearing of his throat, that she should stop bugging him with her irritating stories about writing and this Leroyan, or whatever his name was.

The taxi driver seemed to be waiting for Dino to bring his agitated thoughts to a close. When he stopped the coughing, she tipped her head sideways and smiled coyly at him in the mirror. “Under the weather?”

“Oh, no, I’m fine,” he lied hastily. He did not want the dogged driver-author to start recommending local saunas where he might sweat out all his hidden aches and pains and enjoy a massage with an agile masseuse to soothe him to sleep. (And, who knows, maybe wake him tenderly afterwards.)

These thoughts, which came from nowhere, sent Dino eyeing the cab driver’s muscled shoulders and bare arms with a quick, laser-sharp glance. He swallowed his spit again. God no! He mustn’t get lured into some dry erotic fantasy now. That was the last thing he needed, he silently chided himself, drumming the fingers of his right hand on his thigh.

While he strictly forbade himself from thinking about such things, the cab driver was slowly unbuttoning three buttons on her leopard-skin stretch top, and with a well-attuned ring of optimism, said, “Back to Saroyan. Don’t you find his life story inspiring?”

Dino flinched. That Saroyan again. And now inspiration to boot. If there was anything that could kill Dino’s mood and shrink his mental and physical potency it was the word inspiration. He had listened to his fill of it during his studies and at his first job. Many of his professors and colleagues at work had claimed that everything could serve as a source of inspiration. Poverty, a lost sports match, a break-up with a girlfriend or boyfriend who was not amused by stories about coconuts and swimsuits. But Dino did not buy the theory of Utopian optimism whose banner, as far as he could tell, was Inspiration.

The driver read Dino’s failure to respond to her question as his acquiescence. She shot him a sexy smile in the mirror.

Trapped in a vortex of clashing thoughts, Dino had no choice but to nod lightly and blurt, “Sure, Saroyan’s story is inspirational all right.”

The driver was pleased with his schoolboy response. “You see, like I said, Saroyan’s hard knocks moved me to write my life story. My autobiography, actually. It’s called Marilyn Monroe, My Mother.”

Dino flinched again. Though he had expected her to start reciting Hollywood-style bombastic book titles that would probably never see the light of day, the one she came up with did surprise him. She had written an autobiography with a title featuring Marilyn Monroe herself, no less. The driver’s supposed mother. Dino choked back laughter. He did not want to mix his irony with the cab driver’s fantasy life. He knew a few women and men who had made up stories about exciting adventures they had never taken part in. And all that just to impress themselves and those whose lives were even flatter and less exciting than theirs.

The silence—supposed to show the taxi driver the length and depth of Dino’s surprise in response to her using the name “Marilyn Monroe” and the noun “mother”—stretched beyond the customary time limit of five tense seconds. Dino, however, was the exception to the rule. He loved analyzing, weighing, criticizing and giving himself more time in any conversation, voluntary or otherwise. That is why he left the cab driver waiting impatiently for his response.

To underline his sudden control over the childish situation, Dino scratched his knobby elbow and glanced again over at the driver’s soft profile. Judging by her looks, the way she spoke and thought, she seemed to be a step ahead of the usual liar-author-amateur because she had written that Marilyn Monroe was her mother. Not a bad idea actually, he mused. But based on what he knew about Marilyn Monroe, he figured the blazing actress was a major lure for many who were building a hollow glory and, of course, turning an easy buck. So, the mystery was solved. This was what the driver was after, her own five-minute piece of the fame pie and the money that came with it.

Gloating over his insight, Dino grinned masterfully.

A little taken aback by his wordless grin (after all she had just told him her mother was Marilyn Monroe), the driver smiled once more into the rear-view mirror, catching Dino’s knowing gaze.

Sighing, he looked tactically over at Veljko who was still fast asleep, exhaling noisily through an open mouth. Then he looked back at the mirror, at the profile of the suddenly disgruntled driver. While he watched the right side of her forehead out of the corner of his eye, over which her blond, wayward lock of hair was at liberty, the angle of her pert nose and the corner of her pressed lips, he could not deny a slight similarity to Marilyn Monroe. But cosmetic surgery today could turn anyone into anyone else, he quickly added, coughing. His throat hurt more than ever.

“You know who Marilyn Monroe was? No?” she finally asked in a dry, instructor’s voice.

Dino started to say something biting, such as: No, I have no clue who M. M. was, but I do know that my old man hid pictures of her under the empty beer bottles in the garage. But the driver’s amicable gaze reminded him to be polite. And besides he didn’t want her to launch into an explanation of who Marilyn Monroe had been and what sort of connection that Zeeroyan fellow had with the two of them. So instead he murmured, “Yes, yes, I know who Marilyn Monroe was.”

The cab driver tipped her head slightly to the right. She seemed to be unsure as to why Dino wasn’t showing more interest in her life story with Marilyn Monroe in the lead role. Everyone wanted to know about her. In any combination with other people, the very name Marilyn raised eyebrows. She sighed lightly, turned to look at Dino, and asked him with a studied nonchalance, “Did you know Marilyn Monroe was one of the rare Hollywood actresses who never had a single surgical correction done? Not even her nose. Or her eyelids. Or her lips. Or her ears. Or her breasts. She was naturally perfect.”

“Yesirree, naturally perfect,” answered Dino quickly and readily, shifting his long legs from left to right. The persistence with which the driver was trying to draw him into a conversation reminded him of the people who were forever after their five minutes of limelight. Once he saw a TV show about women and men who hired and paid dearly for a so-called ghost writer who under their name wrote some scandalous drivel that millions of people read only because their own lives were even hollower than the lives of the drivel-scribblers. On the show he had seen a middle-aged man who had claimed unequivocally that he had the documents to prove he was the great-great-great-great grandson of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene and that he possessed all of Christ’s divine gifts. To prove this he explained how as a twenty-three year old he had fallen from the tenth floor of the building where he’d lived and survived, but went into a coma from which he awoke fifteen years later. The first thing that occurred to him was to stretch a line between two skyscrapers in New York and walk across it with no balancing pole. He did exactly that. Then he wrote a book about how he had known from birth that he was the great-great-great-great grandson of Jesus Christ and his follower, Mary Magdalene. The book sold well for a few months thanks to the outrage of members of certain religious groups who raised enough dust about what were, according to them, blasphemous assertions, and that lent him unwarranted publicity.

But who is to decide what is reasonable and what is unwarranted? Dino was leery of taking his critical thinking this far.

While he watched the right side of the slender but sturdy neck of the agile driver from the back seat, a small ironic grin spread across his face again. Now he was certain she was one of the many authors who were after a quick splash. Something in the way the driver held her head slightly tilted and glanced up at the mirror now and then reminded Dino of TV fame hunters. Many of them stared just as suggestively at the anchors of the shows they took part in, tilting their heads slightly like a hungry bird. And all those birds demonstrated convincingly that they were blood relations of famous dead people, mainly actors, princesses, kings, queens, actresses, presidents killed in assassinations, even Russian tsars.

Judging by the title of the book that she’d mentioned, Dino ranked her among those after genealogical fame. She wanted to be recognized as Marilyn Monroe’s daughter, not just some nameless cab driver. What was the difference between the two? Dino thought briefly about it while running his tongue down the inflamed roof of his mouth. The difference was in the money earned and a handful of pictures published in cheap gossip rags, he had to conclude while probing the painful spot at the very back of his throat with the tip of his tongue.

The earnest cabbie, however, would not let Dino throw her off course. Raising her husky voice a notch, with a studied melancholy, she tossed to him over her shoulder, “My favorite film that Marilyn stars in is Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.”

Dino flinched, lowered his tongue, and replied, “Yes, that is true.”

His ambiguous words hung in the humming air for a few sear seconds.

The driver released a throaty huh and coquettishly turned her profile toward Dino again. “So how come you’re not interested me?”

Dino swallowed a wad of spittle and deflected the woman’s snare with a diplomatic response: “But I am interested. I cannot believe that I am in a cab with Marilyn Monroe’s daughter.”

What he had wanted to say was that he couldn’t believe he was being driven in a cab by M. M.’s daughter, but, again, he did not want to sound churlish or coarse.

The cab driver of course, was perceptive enough to see through Dino’s ironic tone and his choice of words. She was used to peculiarities in the behavior and speech of her customers. And besides she didn’t get her degree in American literature and psychology at Golden Gate University in San Francisco for nothing!

The silence in the cab lasted another few questioning seconds.

The patient driver finally straightened up her tilted head and pursed her red lips flirtatiously. “You’re teasing me, I know, but really, I am Marilyn Monroe’s daughter. She is my biological mother.”

Dino nodded. He figured the adjective biological played the lead role in what the driver had said. This resonant adjective was needed to underline the scientific legitimacy of her story and stir in him a natural curiosity, even sympathy. After all she had lost her mother. Marilyn Monroe, no less. This shocking fact paved the way for all sorts of questions. The first might be: who had raised the little girl who now, forty years after the actress’s death, was chauffeuring him in her cab? No, thank you very much, Dino was not interested in hearing this fabulous story.

The driver checked the mirror again. Her gaze expressed both self-confidence and vulnerability.

Dino’s gaze involuntarily met hers in the mirror. Something in the woman’s eyes drove him to cough again and say, “Forgive me for saying this, but somewhere I read that Marilyn Monroe had no children.”

The cab driver sighed deeply, briefly holding her breath. Her face was tense as if she were poised to dive into an invisible body of water. Then she released her breath, relaxed her face, and answered, “Yes, I know. That was a lie spread by the very people who murdered her.”

This tough charge, heavy with weighty words, led Dino to blow his nose and draw in his shoulders as if he were suddenly chilled. Skittish nerves thrummed through his restless fingers. He did not know what to say. He finally coughed and mumbled that he was not aware of the fact of these lies. He wanted to throw into his sentence the adjective sad (fact), but he didn’t. He knew that this would sound artificial and trite. (Like, after all, everything that had gone on until then.)

The driver went on talking about Marilyn Monroe in a calm but suggestive tone. “Yes, sad to say, my mother was murdered. Her killers for years tried to silence the voices of those who knew how she died. They claimed it was all a conspiracy theory fed by gossip columns. But the truth will win out in the end, am I right?”

Dino nodded once more and noisily cleared his throat. Sounding like a bumbling police inspector, he asked, “And do you know who killed Marilyn Monroe? I mean, your mother?”

“You bet,” answered the driver and turned back to him. She looked steadily at Dino over her shoulder. After a few seconds her mysterious gaze melted on his pale face.

Scratching his chin like a bad actor, Dino wanted to ask the driver how it was that she, the daughter of someone like Marilyn Monroe, was working as an ordinary cab driver. But his social antennae, always on the alert at the back of his mind ever since he passed his exam at the University in the course “Awareness of the Inidividual and Critical Thinking,” were tying his tongue and whispering in his ear that it wasn’t polite to ask someone a question which might in any way belittle or insult them. So after that warning to himself he shifted gears and asked, politely, “Did you write about M.M.’s murder in your autobiography?”

“You bet,” said the woman, and reaching toward the box on the seat next to hers, she took a brochure off the top and handed it to Dino over her right shoulder.

“Here, this gives pictures of my mother and me and an excerpt from my autobiography. The picture of my birth certificate is on the last page. Everything is crystal clear and one hundred percent true.”

Dino leaned reluctantly forward to take the brochure. As he was taking it from the driver, his gaze dropped to her bare shoulder. Instinctively he leaned a little more forward, letting his gaze slide into the deep cleft of the driver’s bosom.

He noisily inhaled the air around her.

The dense light of night soaked into the woman’s smooth skin like gold powder. A subtle waft of floral perfume, draping her neck like an invisible necklace, undid Dino’s sleepiness in a flash. He inhaled once more and then breathed out. A heat wave washed over him.

“I am Norma Jeane Leone Monroe,” said the cab driver sweetly, interrupting Dino’s irregular breathing behind her scented neck.

He flinched, brushing the sweat from behind his upper lip with a finger. Then, brochure in hand, he sank slowly back down into the seat. “My pleasure, Miss Leone Monroe. Thank you, thank you. I will certainly read your autobiography. Sounds fantastic.”

Norma Jeane smiled coyly. “Excellent. You are so kind. And by the way, you can read the whole book on Facebook.”

“You’re kidding! Really?” said Dino hastily, settling awkwardly into the seat and covering his swollen crotch with the brochure. He cast a suspicious sideways glance at the still slumbering Veljko.

Norma Jeane Leone Monroe and Dino Lučić spent the next fifteen minutes in silence. The whole time he was struggling with his undesired arousal and the muted but lingering scent of Norma’s floral perfume.

She wasn’t struggling with anything.

They finally reached the most famous part of Los Angeles, Hollywood. Hotel Luna Luna was at the western end of Melrose Avenue, surrounded by tall palm trees and an array of lit billboards. On some of them smiled the faces of Brad Pitt, Kate Winslet, Denzel Washington, Halle Berry, Clive Owen, and other grinning film stars. Their movies were showing soon in America’s movie theaters.

“Here we are,” said the driver melodically, stopping the green and blue taxi in front of a semi-circular white and pink two-story building that looked more like a residence than a hotel.

Forty years before it had been an apartment building with ten one-bedroom apartments. There had been an animal shelter on the first floor. The owner sold the building to a savvy hotel manager who was counting on guests who were not rich, but who could afford a decent place to stay for two, three nights in much-lauded Hollywood. Above the entrance door a “Luna Luna” neon sign went rhythmically on and off. The rooms looked to the west, the street side, while the kitchens with their little living rooms and bathrooms faced south, overlooking a pool surrounded by low shrubs.

Dino and Veljko had first stayed at the Luna Luna the year before. The hotel had been recommended to them by Mike O’Hara, director of the import department at B&B Brothers, Inc.

The neon hotel sign that was turning off and on lit them in regular intervals as if it were an automatic camera with a flash attachment while Norma Jeane waited patiently for gangly Dino to wake up sleeping Veljko,.

Veljko finally woke up. Confused, he looked to the left and right.

“Where are we?”

“We’re here,” said Dino, and with his large hands he curled up the brochure the cab driver had given him fifteen minutes earlier.

While Veljko was pulling himself together, Dino pushed the roll of paper into his pants’ pocket and turned to look at Norma Jean Leone Monroe.

“Thirty-one dollars,” she said with a smile.

Dino tucked his fingers into the little pocket on his blue shirt. There was the money he had prepared, while still on the plane, to pay for the taxi. He took two twenties out and handed them breezily to the driver: “Thirty-six.”

Norma Jeane nodded. “Thanks,” she said and accepted the money. Then she reached behind her seat and fished out a small metal box. She opened it carefully and took out two dollars. She handed them to Dino with a warm smile.

He took the two bills from her with a sigh. Then he shot a questioning glance at her, tilting his head like a wary bird. Norma Jeane had been supposed to return him four dollars, not two.

Reading his thoughts, her smile broadened. “Two dollars for the brochure.”

Dino scowled, suddenly dizzy. He blinked a few times and looked left and right as if to quell the anger and negative energy surging through his tired thoughts and body. Yes, the driver had taken him, cleverly, for a ride, he thought. And now she had taken his two dollars for that stinking brochure that he wouldn’t have accepted under any other circumstances nor would he pass it on to anyone else. It wasn’t the two dollars, it was the question of having power over one’s own decisions and actions. He wanted to say this out loud to her.

But sleepy Veljko, unaware of the sudden tension between Dino and the driver, asked hoarsely, “So, we’re getting out here then?”

Dino swallowed both his spit and his urge to quarrel with the still-smiling driver. Instead he arched his eyebrows and shot her a sour smile, letting her know he had seen through her game from the start so she hadn’t outwitted him by selling him her tall tale of a biography. He shoved the two dollars theatrically into the pocket of his shirt.

“Come on,” pleaded groggy Veljko.

Dino nodded, wiping the smile off his face.

Veljko arched his eyebrows and took a deep breath of the air-conditioned air.

The driver, however, had not stopped smiling. What’s more, she was assailing Dino once again with her insistent cheeriness.

“Have a great time in Los Angeles, sir.”

His voice laden with irony, Dino snarled through clenched teeth, “Miss Leone Monroe, or whatever your name is, you are a cunning business woman.”

“I do my best,” replied the driver coquettishly, taking in with her self-confident gaze Dino’s effort to keep control of himself. Then she got out of the car and went back to the trunk.

Dino took several deep breaths, wanting to rid his mind and body of the anger. But vestiges of Norma’s floral fragrance tickled his hoarse throat. He coughed.

He and Veljko got out of the cab and went over to the trunk where Norma Jeane was standing, still smiling. While they took out their luggage she said to them, politely, “Gentlemen, if you ever want to see the town or go for a drive somewhere, let me know. My email and phone number are on the brochure.”

Surprised by her professional audacity, Dino answered with audible irony, “Thank you so much, you are very kind, but first I must read your excellent biography. And then we’ll see where we’ll go and how.”

Veljko looked over at him, surprised, and asked, sleepily, “Did I miss something while I was sleeping?”

Dino shook his head.

Norma Jeane Leone Monroe smiled again, tossing her hair back. Then she turned, and, swaying her hips, she went back to the driver’s door. She took her place at the wheel and waved blithely to the men.

Dino and Veljko stared after her, clutching their suitcases and computer bags like starving school kids.

The nighttime lights of Los Angeles soon absorbed Norma Jeane Leone Monroe and her taxi into their thirsty skin.

Dino’s and Veljko’s hotel suite was on the second floor. As soon as they stepped into the stuffy living room, Dino took in a deep and grateful breath of the stale air. His dizziness subsided at once. The anger and thoughts of Norma Jeane evaporated as soon as he and Veljko dropped their suitcases to the floor by the checkered sofa that set the sitting area apart from the kitchenette. Then they dropped onto the hard three-seater, taking their cell phones out of their black bags. They quickly tapped out messages to their wives that they had arrived safely and that they’d be in touch tomorrow.

And then, as in a smoothly rehearsed play, they got up from the sofa, grabbed their things and went into the largish bedroom. There they were greeted by a spacious king-sized bed. On both sides were brown, varnished nightstands. On each stood a portly lamp next to which were an electric clock and a white telephone. Across from the bed was a shelf unit with rows of drawers and a TV hung in a square space at the heart of the unit. To its right was a round table with three upholstered chairs, while to the left there was a desk with leaflets and guides for touring Hollywood and Los Angeles.

In silence Dino and Veljko slipped the laptops from their cases and placed them on the desk. Before the next movement of their simultaneous unpacking routine, Dino quickly removed from the pocket of his pants the rolled-up brochure that Norma Jeane Leone Monroe had sold him and set it down next to his laptop. Then they unpacked their dark-blue suits and hung them on wooden hangers in the closet. Next they took out toiletries, clean boxers and white T-shirts for sleeping. The two friends and business partners did all this in tandem, wordlessly, as if in a silent movie. It was as if they were rehearsing for an event that required speed and a special sequence for the actions.

“Is that meeting with O’Hara tomorrow morning at nine or at ten?” Veljko finally broke the silence.

“Nine,” replied Dino, without raising his eyes from the white T-Shirt in his hand.

“Will we get something there to eat or will we have a bite here before nine?”

“We’ll see,” answered Dino, still focused on his T-shirt.

“OK,” said Veljko, his stab at English.

Shared travels often force people to do the same or similar things in tandem or do what they need to do in a strict time frame. For some this can be real hell. For others, like Veljko and Dino, it had become routine. But not all things can be reduced to simple routine.

Veljko was the first to go into the bathroom and shower for five minutes. He came back into the room with a little more bounce in his step, pulling the narrow white T-shirt down over the waistband of the blue cotton boxers. His powerful body still showed the muscles of a former rower. He lay down on the left side of the bed, near the window, and yawned.

“I am dog-tired.”

“Me, too,” said Dino and went into the bathroom. The forty-minute drive through congested Los Angeles and the sly cab driver who had managed to sell him her cheap life story for two bucks had worn him out more than the trans-Atlantic flight.

When Dino came back into the room, refreshed, Veljko was already fast asleep. He was huffing as noisily as a steamship.

Dino lay on the right side of the bed and switched the lamp off on the night table. He stared for a minute at the ceiling, shut and opened his eyes. But sleep adeptly eluded him. Then Veljko’s rhythmic huffs began to grate on Dino’s nerves. His rising edginess reminded him that he had forgotten to take his melatonin pill before they flew out of Frankfurt. Melatonin would have changed the biorhythm of his body and his mind. The nine-hour time difference would have melted away in minutes. How could he have forgotten? But better not think about that now. Any agitation would only make it harder for him to sleep. Should he turn on the TV? News was usually soporific. Though American newscasts were different than the evening news back home. There was always something happening, he fretted restlessly.

Finally, after some twenty minutes of debating with himself, Dino decided he should relax completely and think about nothing. But, out of spite, mental images from the trip began flashing through his mind. Among them the profile, neck and shoulders of Norma Jeane Leone Monroe began rhythmically to appear. Then her face with its make-up, her seductive smile, her plunging neckline and her perfume completely enthralled Dino’s mental and sensual spheres. Before he sank again into these compelling reveries, he opened his eyes and sat up. He swallowed spit. His throat was really sore. Irritated, he switched on the lamp. Damn her, Norma Jeane Leone Monroe. That charlatan was the last person on earth he wanted to be thinking about now. But he couldn’t stop.

Dino checked the electric clock by the lamp. It was 11:09. In Split it was already the morning of the next day, 8:09. He would usually be in the kitchen at that point drinking the last sip of the coffee his Karmela had brewed for him.

Karmela? He should be thinking about her now. Her serenity would surely help him get to sleep. But coffee he mustn’t think about. Its fragrance would wake him even from a coma.

Sighing he looked over at slumbering Veljko on the other side of the bed.

Veljko read Dino’s agitated thoughts telepathically and nearly inaudibly mumbled, “A double, please, for me.”

Dino looked over at him, surprised.

Veljko only smacked his lips.

Dino felt like talking. “Hey, Veljo, were you stung by a tse-tse fly?”

“A whole swarm,” mumbled Veljko and turned over onto his left side.

Dino took a breath and surveyed the room. His gaze stopped at the desk on which among other things, was the rolled-up brochure from Norma Jeane Leone Monroe. Struggling for a few seconds between the impulse to get up and take it and his reason that advised him to lie back down and try to go to sleep, he became even more restless. Impulse won. He got up and in two long strides was at the desk. He snatched the rolled-up brochure and went back to bed. Impatiently he smoothed it out, watching how the title began to appear under his fingers in blue lettering: MARILYN MONROE, MY MOTHER. Under the title in finer print were the words: The Autobiography of Norma Jeane Leone Monroe.

There were two photographs of Monroe, platinum blonde, one next to another on the front, dressed in swimsuits. On one, she was in a white two-piece, on the other, in a red one-piece. In both she was smiling flirtatiously at the viewer. But seconds after he had glanced at both pictures, Dino noticed that the Marilyn on the right was shorter and plumper, while the one on the left was taller and more slender.

He sighed deeply and scratched his bare knee. So one of these Marilyns was real and the other, who knows? Fake or real, too? he mused while his greedy gaze flicked back and forth between the left and right Marilyns and finally rested on the juicy pursed lips of the one on the right.

As Dino’s finger slowly rose into the air with the intention of coming down on the firm, half-parted paper lips, his penetrating analytical bent and unconscious fears won out over his normal sex drives.

Again he painfully gulped back spit and again he looked at the picture of Marilyn on the left side of the first page of the brochure. Her face was identical to the face on the right. But then, again, the body of the one on the left was more slender and lithe. He decided analytically, with a certainty, that this was a photograph of the real Marilyn, too, whose figure some clever photographer had touched up a little so that the self-proclaimed actress’s daughter Norma Jeane Leone Monroe could claim this was she.

All of Dino’s musings about Marilyn Monroe’s appearance, the identity of the cab driver, and, finally, his own suppressed desires, irritated him more and more.

On the other side of the bed Veljko snored loudly and smacked his lips now and then.

In order to extricate himself from the chaotic trap of wakefulness into which he had stumbled, Dino once more spread out the brochure and then flipped the page. On the right was a black-and-white photograph of Norma Jeane Leone Monroe’s birth certificate, while on the left was a text bearing the title “My Golden Loves.” He scratched his chin and began to read.

My Golden Loves

Goldie, a golden retriever, was my first love. Marilyn Monroe, the golden goddess and my biological mother, was, and still is, my second love. Golden-mouthed Estella Dalixia Martin Gomez Velasquez, my first girlfriend, was my third love. My other loves were silver, bronze and iron. Some of the iron ones left scars on certain parts of my anatomy. (More about that later.)

Two important squares on the chessboard of my life are held by my adopted parents, Marietta and PIetro. They were my good angels. Especially my mother, a stylish housewife with a modest idea of what to do with her leisure time. In the afternoons, after lunch, she liked to smoke cigarette after cigarette, chat on the phone with her sister Paola, polish her gold bracelets, brooches and chains with a rag soaked in vinegar, and scheme about how I would become Somebody one day. Mama was never too clear on who that Somebody would be. (Hand on heart, my talents were modest. But I was pretty. At least so they told me.)

My Papa, Pietro, and his brothers, Gino and Domenico Leone, were the proprietors of Catania, a small restaurant in southern Los Angeles. All three of them spent their days and nights there. At night they usually played cards with the fat cats from town hall, drank whiskey, made eyes (and more) at the waitresses, and waited patiently for the day when, by some miracle, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin would walk in the door and join them at cards.

Mama often complained bitterly that Papa was married to the Catania and not to her.

The family on Mama’s and Papa’s sides were all from Sicily. É vero. Our family parties were like a send-off at a train station. Everyone hugging and kissing each other on the cheeks as if they were about to leap up onto a train that would be taking them into the unknown. Even the expressions on the faces of these relatives of mine showed just how attached they were to each other. But this bond was clearly defined by all sorts of demands, advice, and conditions. And slaps on the cheek, accompanied by a short, imperative “Eh”.

But Goldie, my golden retriever. She was the one who taught me about unconditional love. The following story demonstrates the efficacy of her unswerving dedication. A week after we brought Goldie home, her devoted glances and protective behavior spurred my mother Marietta to tell me a secret which, as I later learned, was shared only by Papa and Aunt Paola: that I, like Goldie, had been adopted. This news thrilled me. I wanted to be like my beloved retriever in every way.

It was destiny that sent her to me. This is how it happened.

Several days after my sixth birthday (I was born on August 3, 1962), I told Mama that I wanted a dog for my birthday. Papa didn’t like dogs. Mama, however, made a solemn promise that she’d get me one, but only if I promised to look after it.

Nothing easier than to look after someone you love.

That Saturday the three of us went to an animal shelter. It was on the first floor of a pink two-story building on Melrose Avenue in western Hollywood. When we stepped into the large room piled high with metal animal crates, we were surrounded by the pungent odors of animals and the sweetish perfume of the lady who worked there. She stood behind a worn table a few steps from the front door. On the middle of the table lay a gray typewriter surrounded by jars holding ballpoint pens of different colors and little sacks of candy. The lady was young. She had long violet-colored hair teased up in a beehive. She looked like a combination of a lilac bush and Pekinese. I liked her cute face.

After she greeted us warmly, Miss Jorgeser stepped out from behind her desk and came over, cracking her long fingers. With a smile she said that every dog and every cat at the shelter cost two dollars. The money from the sale went to the Animal Protection Fund.

My mother nodded. Papa mumbled something under his breath. I was afraid he’d say that two bucks was too expensive for buying just one dog. Instead he sniffed like a dog and looked away impatiently. He was always in a hurry, especially when there were women talking.

The shelter had two hundred dogs and a hundred cats. The poor things stood or sat in their crates behind bars and waited for someone to stand in front of them and smile. With this smile began every, even the briefest, love.

Miss Jorgeser took us slowly from crate to crate. The eyes of all the dogs and cats behind the bars were sad. Their gaze made me sad. But when I finally caught sight of Goldie, the golden retriever, at the end of the room, I jumped up and down, thrilled, and clapped my hands. Her golden fur was like my hair. Her wide-open eyes were full of hope. As soon as our eyes met, we knew we belonged to each other. If I had had a tail, I would have been wagging it happily, betraying my joy at the encounter, which profoundly shaped my ability to learn how to love someone in the coming years and survive the departures of those who left me.

When Papa finally handed Miss Jorgeser the two dollars for Goldie, she looked me over. Her speckled green eyes jumped between my blond curly hair, my blue eyes, and the birthmark to the left of my upper lip. Then she blinked and looked over at my Mama and Papa, gauging precisely the shade of black of their hair and eyes.

After she had checked us out, Miss Jorgeser told my Mama in a sweet voice that I looked just like that actress, Marilyn Monroe. I had hoped she would say I looked like Goldie. Mama quickly drew her dark eyebrows into a stern line and snapped that she, too, had been blond when she was little.

It was there, at the animal shelter, that I first heard the name Marilyn Monroe. For the next few years I heard from all sorts of people, plenty of times, the comment that I was remarkably similar to that actress, Marilyn. But until I was eleven, when my mother, poor mama Marietta, came down with leukemia, I wasn’t particularly interested in M.M. I saw pictures of Monroe in the papers, on TV and on the wall at Papa’s restaurant, but I didn’t pay them much attention. The only thing I liked on the actress’s face were those long false eyelashes that cast a shadow over the outside of her cheekbones. I thought how one day I, too, would wear false eyelashes. Their length and thickness gave the eyes depth. (I must have heard that from my Aunt Paola. She also wore false eyelashes).

A few weeks before my ailing mother died, she told me I should take my birth certificate from the bottom drawer of the old cupboard in the living room. It doubled as my adoption certificate. Mama’s death was the first sad thing I knew in life.

After her death, Papa withdrew for a time into himself, and then he withdrew to the arms of Jenny, a generous waitress. Goldie took over the role of Mama for me. She encouraged me to eat with her protective gaze when I didn’t feel hungry. To write my homework when I didn’t feel like it. To fall asleep curled up next to her when I was scared of something.

One afternoon the two of us finally read my birth certificate. On it was the following information:

1. Place of birth: Los Angeles

2. Mother’s address: unknown

3. Name of the hospital or institution where the child was born: unknown

4. First name of the child: Norma Jeane

5. Last name: unknown

6. Sex: female

7. Number of children born at this birth: probably one

8. Date of birth: Friday, August 3, 1962

9. Father: unknown

10. Child’s race: white

11. Doctor or midwife at birth: unknown

12. Place of registration: Los Angeles, Health Department

13. Adoptive parents: Marietta and Pietro Leone

14. Date of adoption: July 7, 1963

15. Address of adoptive parents: 616 S. Olive Street, Los Angeles, CA 90014

Who Am I?

On Sunday, August 5, 1974, two days after my twelfth birthday, I happened to hear on television that on that day, twelve years before, the actress Marilyn Monroe had died. While the announcer with her thickly made-up lips and eyes said that the dead actress was found by her maid in the bedroom, a still living Marilyn on the screen sang “Happy birthday to you” to the American president. She was wearing a tight flesh-colored dress with a deep neckline. The dress was slicked to her body as if it were a wet glove. The actress’s half-shut eyelids were fringed with long false eyelashes. Their thin shadows played on her porcelain cheeks.

The announcer went on to say in a dramatic tone, among other things, that the cause of death for M. M. was an overdose of sleeping pills. Then she made a point of saying that some of her friends did not believe this official statement. What’s more, they claimed that the actress was nine months pregnant and that she was killed by the father of the child, who at that time was the most popular president in the world. Taking a breath, the speaker added in closing that there was no material evidence for this scandalous and controversial assertion.

But it etched itself in my memory and several years later it gave me food for thought.

Read the rest of this chapter on Facebook at Norma Jean Leone Monroe.

Thank you

Dino took a deep breath of the stale air of the room. What he had just read sounded like a flimsy Hollywood story that, he had to assume, would have an “inspirational ending.” Stories like that sold well. People loved reading sad stories with happy endings. The fact that the sun sets in the evening and then rises again the next morning steals the breath of those who get up at dawn, mused Dino cynically.

And now, breathing deeply himself, but for other reasons, Dino looked back at the electric clock on the night table. It was eleven thirty. Exhausted, he stretched his arms wide as if to free himself of the oppressive presence of Norma Jeane Leone Monroe. The brochure fell from his loosened fingers to the floor. He closed his eyes. But, to his horror, Norma Jeane’s third love strode imperatively into his thoughts, the mysterious golden-mouthed Estella Dalixia Martin Gomez Velasquez.

Punch-drunk Dino began painfully gulping down spit again, at the same time measuring in his mind’s eye the bare, bronzed body of Estella Dalixia, Veljko’s slumbering voice undulated like a slow tidal wave through the quiet room.

“The two most important things in boatbuilding: safety and balance. OK.”

* *

READ THIS IN THE ORIGINAL

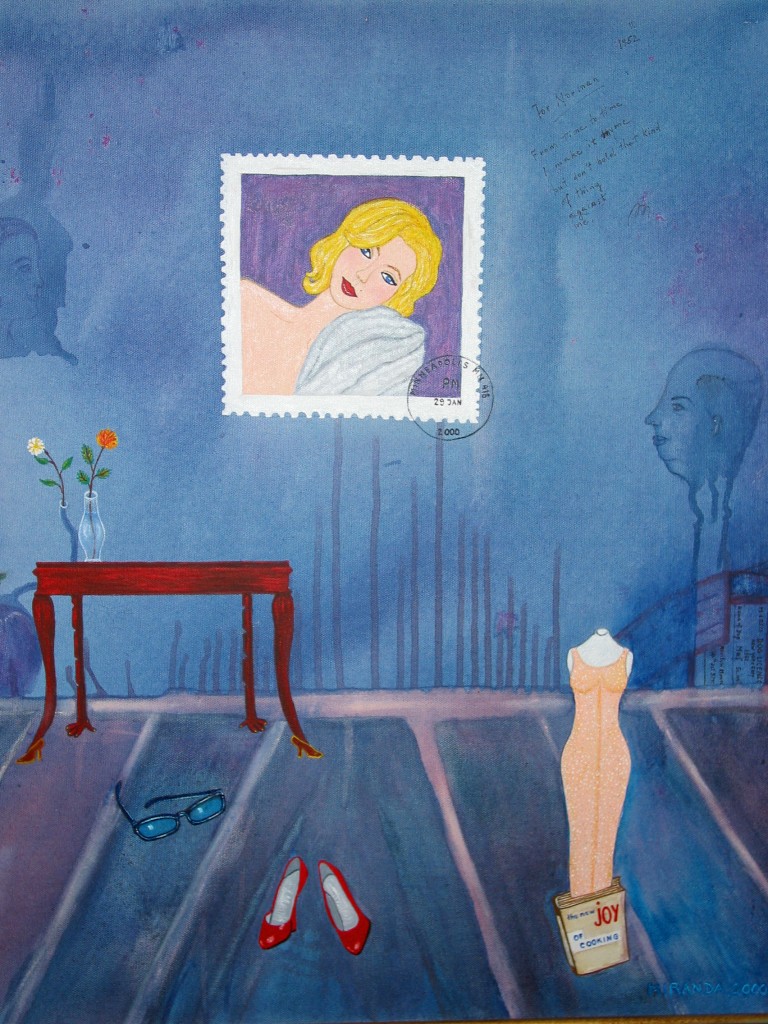

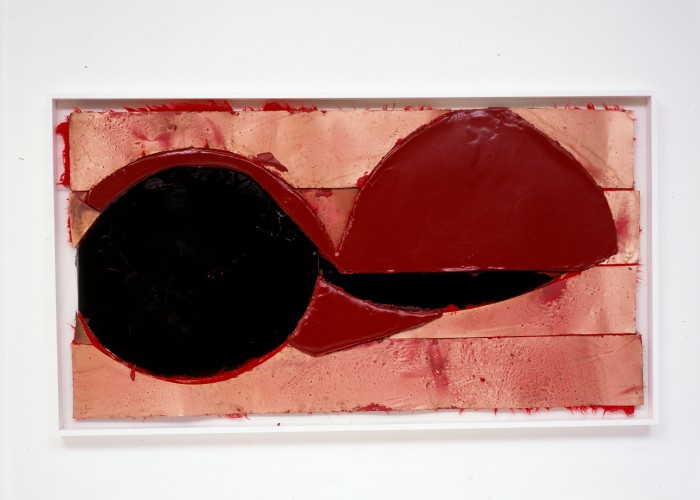

Featured image: “Hitchcock & Marilyn” (2001) by Neda Miranda Blažević-Kreitzman. Images in the text: Johan Barrios from the series “Surfaces” (2010). Curated by Marisa Espínola of Espacio en Blanco. (More)

[ + bar ]

Ravensbread (selections)

Nuno Ramos translated by Adam Morris

Geology Lesson

There’s a layer of dust covering things, protecting them from us. Dark sooty powder, fragments of salt and seaweed, tons of grainy... Read More »

Book Market [lviv]

Natalka Sniadanko Translated from Ukrainian by Jennifer Croft

“No photos,” barks the geezer wearing the typically Soviet hat with the visor, synthetic leather sandals, an untucked shirt, and pants... Read More »

Alfredito

Liliana Colanzi translated by Chris Meade

Once, when I was a little girl, I saw a pig being killed. It was summer. Flies were launching themselves against the windows.... Read More »

Passagem Literária da Consolação

Julián Fuks

Chamemos de mal-estar nas livrarias. Sei que não sou o primeiro a sofrer desse infortúnio, sei que não serei a última de suas vítimas. Em algum... Read More »

![Book Market [lviv]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/tocada-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...