Natalia Litvinova

translated by Andrés Alfaro

DUST

My voice seems not to come from me but rather from another throat

buried within the depths of my own.

I am like a collection of walls surrounding what I am.

Someone must have built this great wall.

If there are men who fly like feathers, why can I not

move when I move? I smell of stone and dust,

I wear the traces of those who touch me.

I am dust, stone. I do not know who my father is.

* *

FEAST ON MY SNOW

I whisper to the birds: leave my poems, feast on my snow.

I whisper to the snow: get out of my poems,

dig in, taste the birds’ eggs.

Birds’ eggs take wing.

Do not let the shell of stillness devour you.

* *

THE SPRING OF BALTHUS

Balthus’ desire was never realized. The white of the

girl’s underwear brought back the first snowfall of his youth:

he went trouncing through sparkling fields after a wounded quail.

The bird could not take off and dragged its feet, leaving behind

an intermittent calligraphy. When he caught up with it, it lay dead

in the snow. Daily throughout winter he visited the tomb of ice.

One warm day the quail’s body disappeared.

Balthus cursed springtime. And the girl.

* *

An Introduction to the Poems of Natalia Litvinova by Her Translator into French

by Stéphane Chaumet

translated by Andrés Alfaro

Proust’s notion that “masterpieces are written in a sort of foreign tongue” is often quoted yet rarely employed in literature. Some authors achieve such foreignization through the flow of one language into another, in the abandonment of the mother tongue in order (to be able) to write. Moving language. Conrad left Polish for English, Beckett English for French, not to mention the Romanians Cioran and Gherasim Luca, famous examples where the strangeness infused in the tongue, the adopted tongue, was subtle yet profound. Perhaps in the end it comes down to style.

This is the pervading impression we have upon reading Natalia Litvinova, who crossed over from her native Russian to Spanish, the language of her estrangement. On arrival in Buenos Aires, Litvinova is ten years old and does not speak a single word of the language she will eventually choose to write in. Her parents decided to flee Gomel (the second-largest city of Belarus, close to the Russian and Ukrainian borders) where she was born in 1986, not far from Chernobyl, four months following the tragic nuclear disaster there.

In Natalia Litvinova’s poetry we don’t find the nostalgia of exile but instead the nostalgia of childhood. Or no, it’s not really that. It has more to do with feelings and visions, not memories. Or rather, memories would be like a mirror that broke into a thousand pieces across the ocean, and writing doesn’t attempt to put the pieces together but to communicate and recreate a feeling in each shard that re-surfaces from oblivion. And hence there appears snow, a forest, a father’s uncertain footprints, dust, the shadow of Pripyat… Natalia Litvinova has eyes, but they do not always see the same things that ours do; she has a body, but it does not perceive the way our bodies do, though everything may seem familiar. When she showers, she doesn’t simply cleanse herself, she thinks about the steamy water burning her skin and dragging with it the scent of her vagina: “I move my hand toward my vagina, then to my nose. the odor is lost. it escaped down a dark drainpipe toward the street. it seeped into the autumn leaves. they’ll smell me, the rats, the stones, the sparrows. maybe the kids launching toy paper boats.” When she looks at a Balthus painting, the white undergarments of a young girl bring her back to the snow of childhood and fuses into the painter’s snow. She comes to find a false innocence that both intrigues and disturbs. We start reading, and we topple into a world—her world—where feelings, visions, and images, both personal and unexpected, manage to move us, like a kiss that also bites, or vice versa.

* *

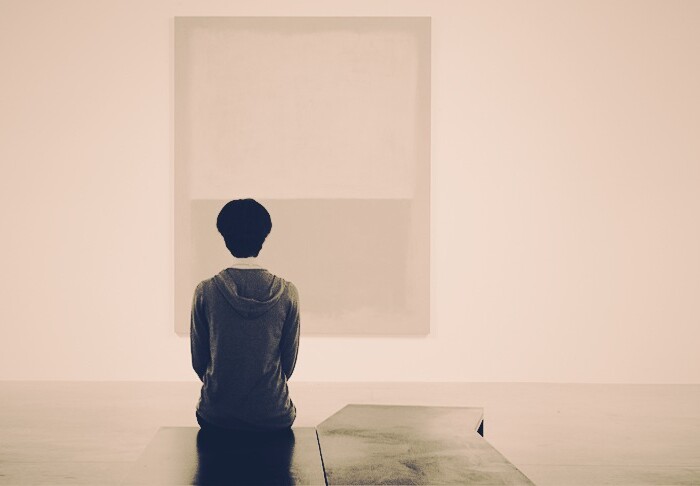

Image: Sofía Flores Blasco

[ + bar ]

Luna Miguel

YOU HAD GLITTER ON YOUR FINGERS

I can hug the old refrigerator before they take it away. I can write that you had glitter on your fingers and that burning glitter... Read More »

The Red and the Black

María Gainza translated by Jane Brodie

I’m scared. I’m sitting on a plastic chair waiting to see the doctor. It’s a cold spring morning and I’ve come... Read More »

Junot Díaz: “We exist in a constant state of translation. We just don’t like it.”

Interview by Karen Cresci

Read More »Orellana [valparaíso]

Álvaro Bisama translated by Julia Ostmann

My favorite bookstore is a ghost bookstore. It was called the Orellana and was located in the center of Valparaíso. It closed a... Read More »

![Orellana [valparaíso]](http://www.buenosairesreview.org/wp-content/uploads/la-foto-crop-700x500.jpg)

sending...

sending...